Astronaut Who ‘Fell in Love With Space Photography’ Shares Stunning Timelapse

Astronaut Jessica Meir, who currently resides on the International Space Station, has shared a resplendent timelapse video of aurora lights dancing over Alaska and Canada.

Astronaut Jessica Meir, who currently resides on the International Space Station, has shared a resplendent timelapse video of aurora lights dancing over Alaska and Canada.

A trail camera has recorded a world-first: a red fox attacking and presumably killing a wolf pup.

An argument over what to do with a building at the center of a famous Robert Capa photograph has broken out between authorities in Madrid and the International Center of Photography.

Rode has announced the RodeCaster Video Core, a small desktop device that allows users to connect up to four cameras to create a fully customized video production.

When new cameras are announced, dynamic range is often a significant part of the image quality discussion. When a camera offers particularly fantastic dynamic range, it's big news. Likewise, when a camera's dynamic range takes a big hit in exchange for other impressive features, that's news, too. However, does dynamic range really matter that much?

The American Society of Cinematographers hosted its 40th annual ASC Awards last night, celebrating the best achievements in cinematography over the past year. Oscar-winning cinematographer Michael Bauman took home the most coveted prize of all, the Theatrical Feature Film award, for "One Battle After Another."

Greece has acquired a photo archive that documents the execution of 200 communist prisoners at the hands of the Nazis in Athens.

Meta is facing a class action lawsuit over its AI smart glasses, with plaintiffs alleging that the company misled consumers about how footage captured by the devices may be reviewed.

British motion picture lab On8mil is bringing Super 8 film to the 21st century with a new daylight-loading, reusable Super 8 cartridge system called Re8mil, a first of its kind that promises to make Super 8 filmmaking much less wasteful.

There are now hundreds, if not thousands, of AI apps that can create "professional" images from just a single photo of a person. The only problem? They're not real.

An innovative cube camera could provide a fallback option for photographers shooting film.

Photography has everything to do with light. Therefore, the more we know how it behaves and interacts with our equipment, the greater the chance of getting a successful photo.

The first photo of a ghost elephant captured by a motion controlled camera. The eyes glow in this night shot.

Sigma created an art form out of its Art series of lenses. They are beautiful, professional, and often chosen over OEM options. But there is always room for improvement, and the Art series has been on the market for a minute, so new technology inevitably leads to new updates. It could be argued that the Sigma 35mm F/1.4 Art is one of the most popular primes in the Sigma arsenal, and now we have a successor.

Mountain lions are rare in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, and there's been a buzz in the National Elk Refuge recently where one has been spotted prowling around.

Yashica has announced the Tank, a new compact digital camera designed to emphasize simplicity, portability, and the nostalgic feeling of early digital cameras.

There are many talented, respected professional wedding photographers and videographers. A lot of people do great work for their clients and deliver people with treasured photos and videos from one of the most special days of their lives. However, as controversy after controversy has shown, the wedding photo/video industry is also one rife with malice and scandal.

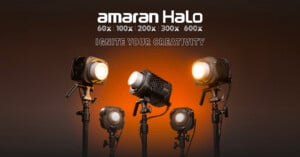

Amaran has announced the Halo Series, a new lineup of studio-focused bi-color COB lights designed to deliver consistent lighting performance across a range of creator environments. The new family includes five models, the Halo 60x, Halo 100x, Halo 200x, Halo 300x, and Halo 600x, with power ratings ranging from 63 to 610 watts.

It has been a long time coming, but the new WideluxX (stylized Widelux•X) panoramic analog camera continues getting closer to release. Hollywood star Jeff Bridges and his wife, photographer Susan Bridges (née Geston), unboxed not only the prototype the company unveiled last fall, but a much more complete camera that looks very nearly production-ready. Jeff Bridges may be an Oscar-winning actor, but his happiness when opening the new WideluxX camera is the real deal.

The Hasselblad Foundation has named South African photographer Zanele Muholi the 2026 Hasselblad Award laureate, the world's largest photography award. Muholi has won SEK 2,000,000 (over $217,000 at current exchange rates), a gold medal, a Hasselblad camera, and a lengthy solo exhibition at the Hasselblad Center at the Gothenburg Museum of Art in Sweden.

To celebrate the annual WPPI 2026 show for wedding and portrait photographers, which wrapped up yesterday in Las Vegas, B&H has a ton of great deals on cameras, lenses, lighting, and accessories favored by wedding, portrait, and event shooters. The wedding, prom, and graduation season is just around the corner, so there's no better time to gear up without breaking the bank.

French photography publication Phototrend chatted with Samyang's head of product planning, Kim Dubin, and Samyang is up to some extremely exciting things, including a flagship 200mm f/1.8 lens that will showcase Samyang's optical engineering chops.

Acclaimed war photographer Paul Conroy died this week of a heart attack at age 61.

Kino, an iPhone video camera app created by Lux, the same people who make the iPhone photo camera app Halide, received a massive update today that adds Apple Log 2 support.

The Center for Photography at Woodstock (CPW) has announced that Sridhar Balasubramaniyam is the recipient of the 2026 Saltzman Prize for Emerging Photographer, which includes a $10,000 award.

Nothing is known for its mostly transparent, ultra-stylish smartphones. However, the company's latest offering, the Nothing Phone 4a Pro, ditches the translucent case everywhere except the large, flashy camera module.

Llano has introduced the AC3 30W Fast Charging Case, a compact battery charger designed for action camera users who need to manage multiple batteries quickly while traveling or shooting on location. The portable charging case can power up to three batteries simultaneously and supports a range of popular action cameras from several major brands.

A wet and rainy San Francisco was the venue for this year’s Galaxy Unpacked launch event and the testing ground for shooting the new Samsung Galaxy S26 Ultra. The Ultra model is priced at $1,299, which is the same as last year’s model. I’m going into this review with the usual intention of testing this phone more as a camera and seeing how it stacks up as a creative tool.

An investigation has alleged that footage taken on Meta's AI smart glasses is being watched by tech workers, including intimate moments.

Harman has announced a funky new film called Switch Azure where the colors swap around -- rendering blues as oranges, yellows as blue, and reds as purple.

Apple's new 27-inch Studio Display XDR looks like a great option for photographers and video editors requiring accurate colors and high peak brightness. However, as eagle-eyed prospective customers are discovering, there are some caveats to consider when it comes to compatibility.

The European Space Agency's (ESA) remarkable and relatively new Euclid space telescope teamed up with NASA and ESA's venerable Hubble Space Telescope (Hubble) to capture beautiful photos of the Cat's Eye Nebula, also known as NGC 6543.

Lomography has released a new Simple Use Reloadable Film Camera that comes pre-loaded with LomoChrome Classicolor film, an ISO 200 color film Lomography launched last October.

In January, news broke that Nikon had filed a lawsuit against Viltrox in China concerning patents related to Nikon Z-mount technology. A couple of weeks later, Viltrox said that despite the lawsuit, it was not adjusting its lens development roadmap. New reports this week claim that lens makers Sirui (China) and Meike (Hong Kong) have both stopped Nikon Z lenses, which is quite the coincidence given the ongoing legal situation with Viltrox.

vivo is taking mobile videography to new lengths in a very literal sense with the X300 Ultra, putting a professional cinema camera into your pocket. This means filmmakers and content creators can now capture professional-grade footage anytime, anywhere, without compromising on quality or creative control.

What happens when you put a small robot into a smartphone and let it control the camera? Honor’s Robot Phone is essentially built on that premise as an Android phone with a built-in gimbal. And the company says it will become a finished product coming to market at some point in 2026, starting in China first.

Apple has announced a brand-new, low-cost laptop, the MacBook Neo. Starting at $599, it is Apple's most aggressively priced MacBook ever, and it sports an Apple A18 Pro chip, like the one the company used in its iPhone 16 Pro smartphones.

GoPro has revealed its new GP3 processor, which the company says will deliver twice the pixel-processing power of the previous generation.

A photographer who had over $12,000 worth of camera gear stolen from a bar in New York is going public with his story in the hope of getting it back.

The United States Supreme Court has ended the long saga over whether an AI can be registered as the author of an artwork after it declined to take up the case brought by computer scientist Dr. Stephen Thaler.

In October, the National Press Photographers Association (NPPA) warned photographers against rights-grabbing credentialing agreements after The Gazelle Group, a major firm known for its sports coverage, offered credentials for sporting events in exchange for irrevocable, free use of photos taken by credentialed photographers. This pay-to-play arrangement understandably irritated photographers and wire services, and the fallout has persisted.

Thousands of professional sports photographers descended on northern Italy last month for the Winter Olympics, coming away with many incredible photos captured using a wide range of equipment from all the major brands, including Canon.