Landscape Photography: The Ultimate Guide

![]()

Landscape photography is one of the most popular photographic genres. It’s easy to get started with the genre, but it can take a lifetime to master landscape photography skills. You don’t need a sophisticated camera or expensive lens, and the skills you learn when doing landscape photography translate to other types of photography.

Table of Contents

What is Landscape Photography?

Landscape photography doesn’t fit neatly into a single box. However, a unifying thread that connects all landscape photographs is that the image features the natural world, although it may include wildlife, artificial objects, or people in it as well.

Put simply: landscape photography is capturing photos that show the grandeur and beauty of the great outdoors.

Many celebrated landscape photos have subjects like mountains, forests, lakes, rivers, and the ocean. However, many influential landscape photos also include a human touch. In an ever-changing world, landscape photos showing our impact on the environment may become even more important.

![]()

The line between landscape, nature, and wildlife photography is often blurry. A landscape photo could be all three at once. Landscape photography has a rich artistic history, and its definition has become suitably broad. Whether a landscape is depicted with hyper-realism, abstraction, or any style in between, it’s a landscape image if the photographer or the viewer says so.

A Brief History of Landscape Photography

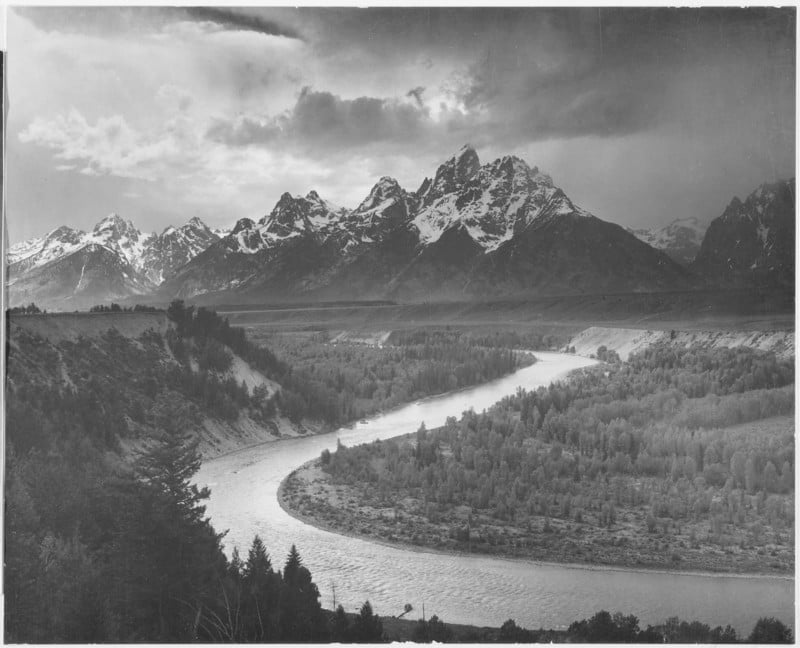

While famous 20th-century landscape photographers such as Ansel Adams may be the first to come to mind when considering the origins of landscape photography, its history is traced back to the very earliest days of photography itself.

Of course, the history of photography is a bit murky. A widely accepted version is that Nicéphore Niépce was the first to use a camera to capture a photograph in the mid-1820s. The early results were crude and required hours of exposure time, so the first portrait was still a way off. However, static objects, such as landscapes, lent themselves well to the burgeoning medium.

Niépce’s associate, Louis Daguerre, then developed the daguerreotype process. This process required only a few minutes and produced clearer results. In 1839, Daguerre released his method to the world at large.

Photography still wasn’t yet practical, but that same year, William Henry Fox Talbot demonstrated a different photographic process using a paper-based calotype negative and salt-printing. Improvements to materials and chemical processes eventually shortened exposure time to seconds and then fractions of a second, making photography more economical.

When you look at the earliest photographs, at least those that have stood the test of time, many of them are portraits. It’s not surprising, as portraiture remains ubiquitous to this day. However, cameras were nonetheless being pointed at beautiful landscapes. In the 1860s, photographer Carleton Watkins captured early photographs of Yosemite and its surrounding areas using 18 x 22-inch glass plate negatives and a stereoscopic camera. He returned from his 1861 expedition with 30 plates and dozens of negatives. His images helped influence the US Congress to protect the Yosemite Valley and ensured that generations to come would be able to enjoy its natural beauty.

Fellow New York-born photographer William Henry Jackson is considered the first person to have photographed Yellowstone in 1871 as part of the Hayden Geological Survey. In addition to capturing stunning and influential landscape photos of Yellowstone, Jackson later photographed incredible landscapes in the American West. Jackson, who lived to the old age of 99, is fondly remembered for his contributions as a soldier, explorer, author, painter, historian, and photographer.

By the late 1800s, despite the beautiful photographs by the likes of Watkins and Jackson, landscape photography – and photography at large – hadn’t yet earned the respect of the artistic community. However, photographers like Alfred Stieglitz, Peter Henry Emerson, and Edward Steichen utilized more painterly approaches in the darkroom, and photography began to cement its place as a legitimate art form. Steichen’s 1904 landscape image The Pond – Moonlight had an important role to play in photography achieving the respect it deserved.

It’s impossible to discuss the history of landscape photography without talking about Group f/64. The group, formed in the early 1930s by western US-based photographers, includes some of the most famous names in the history of landscape photography. The group’s first exhibition in 1932 included prints from Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, John Paul Edwards, Sonya Noskowiak, Henry Swift, Willard Van Dyke, Edward Weston, Brett Weston, Preston Holder, Consuelo Kanaga, and Alma Lavenson. The show ran for six weeks, and its impact was significant. It’s worth noting that the group was somewhat informally organized, and not all the photographers who exhibited their work considered themselves part of the group.

The group, informal as it may have been, did have a generally unifying vision of landscape photography. The group’s work fought against the earlier trend of pictorialism, which had initially convinced the art world to accept photography as legitimate art. Group f/64 aimed to promote sharp, well-exposed, and carefully composed images.

While Ansel Adams is perhaps the group’s most famous member and best known for his beautiful black and white images, he also worked in color at the advent of color landscape photography. On the other side of the country, photographer, Eliot Porter, photographed wildlife and landscape scenes in the eastern US using Kodachrome color slide film. Nonetheless, color landscape photography remained something of an outlier for decades.

In the 1960s, wilderness photographer Galen Rowell showed people the beauty of many remote landscapes in brilliant color. Rowell was also instrumental in developing the graduated neutral density filter with the filter company Singh Ray. Rowell was a prolific and influential landscape photographer until his tragic death at 62 years old in 2002 in a plane crash. His legacy will forever be felt.

Contemporaneous to Rowell were other color landscape photographers like Ray Atkeson, Philip Hyde, David Muench, Luigi Ghirri, Neil Folberg, and countless others. Of course, black and white landscape photography has never disappeared, and influential photographers have continued to work in black and white long after the early pioneers. Photographers like Michael Kenna, Takeshi Mizukoshi, and Hiroshi Sugimoto continue to create significant monochromatic landscape work.

It’s impossible to list everyone who has played an essential role in the development of landscape photography, and we wouldn’t be where we are today without the contributions of the earliest pioneers. They paved the way for modern landscape and worked tirelessly to guarantee that landscape photography became a respected art form.

Landscape Photography in the Digital Age

Landscape photography has become increasingly accessible. The proliferation of smartphones has made it possible for just about anyone to capture landscape images. Long gone are the days when a photographer needed to schlep dozens of pounds of gear and glass slides out into the wilderness to capture a beautiful landscape photo.

Modern landscape photography maintains many of the same components as the earliest landscape images. While the gear has changed, landscape photography maintains a certain timeless quality.

Portraits often show the changing sensibilities of cultures over time, and documentary photographs, like street photography, photojournalism, and sports photography, capture moments in time that are usually easy to date. In contrast, any given landscape could have just as easily been captured decades ago or yesterday.

In an increasingly changing world, with our impact on the environment being felt more acutely than ever, the importance of landscape photography is even greater. Much like photographers such as Carleton Watkins and William Henry Jackson helped convince politicians and the public alike to protect the natural beauty of Yosemite and Yellowstone, and photographers like Ansel Adams enamored people with stunning natural vistas across the US, landscape photographers today have a vital role to play in convincing people in the 21st century to do more to protect our environment now.

Why You Should Try Landscape Photography

There are many compelling reasons to try your hand at landscape photography. It’s a great way to add another element of enjoyment to your outdoor adventures. Even better, it’s excellent motivation to start getting out into the natural world more often. Landscape photography helps you document your surroundings and can be a fantastic way to learn to enjoy the outdoors, whether it’s right in your backyard or halfway around the world, in a new and fulfilling way.

Landscape photography is an excellent way to strengthen your photographic muscles if you want to improve your overall photography skills. Landscape photography encourages technical skills, including proper exposure and tack-sharp focus. The genre also helps you work on your compositional skills. Photographing the entirety of a beautiful scene is tempting. Still, disciplined landscape photography will help you learn what to include in your composition and, perhaps more importantly, what to omit. That skill translates to every possible photo genre.

Landscape photography is an exercise in timing and patience. Sure, your subject is often stationary, but the light is ever-changing, and the best light is often fleeting. You may need to spend a lot of time in one place or visit the same spot many times before capturing your perfect shot. You learn a lot about light when doing landscape photography. That knowledge pays dividends across all types of photography.

Landscape photography is easy in the sense that your subject doesn’t move, and anyone can do it. The gear requirements are minimal. You don’t need an expensive camera, massive lens, or lighting equipment.

While it’s easy to do landscape photography, it will take a lifetime to master the craft. Your landscape photography skills will undoubtedly improve with time and persistence, but there’ll always be room for further improvement. Being easy to start but challenging to master makes landscape photography irresistible.

What Kind of Camera Do You Need?

Despite the ease with which anyone can shoot landscape photos and the relatively low barrier to entry concerning equipment, that doesn’t mean that there aren’t qualities to a camera or lens that make it a better or worse choice for landscape photography. You don’t need fancy gear, but there are undoubtedly better and worse options.

Let’s consider the camera first. After all, it’s the bedrock of any photographic kit. Image quality at low ISO settings is paramount for landscape photography. Image quality comprises sharpness, color range, tonality, and dynamic range. You want a camera that captures sharp, vibrant images with excellent capability to accurately record tones in a scene with highly varied lighting. You don’t need a full-frame or medium-format camera, but all else equal, larger image sensors perform better when it comes to image quality.

A good landscape camera doesn’t require the same features as a camera aimed at photojournalists and sports photographers. These photographers make their money photographing action, so they care a lot about autofocus, shooting speed, and high ISO performance, even at the expense of resolution.

Other considerations aside, photojournalists and landscape photographers will agree that a camera’s durability matters. When outside, weather changes fast, and your gear needs to withstand big shifts in temperature and survive a bit of rain.

There’s no such thing as a completely waterproof interchangeable lens camera, and you should always do your best to protect your gear. Still, some cameras are certainly better than others at handling adverse conditions. Typically, cameras aimed at enthusiasts and pros will stand up better over time than cameras designed for beginners.

For what it’s worth, I’ve never had a camera break due to weather. I carry plastic bags in my backpack and always dry my gear before opening changing lenses, opening memory card slots, or changing batteries.

![]()

You’ll spend a lot of time composing landscape images, so you’ll want a camera that’s pleasant to use. This includes an intelligent user interface, convenient controls, a large viewfinder, and a sharp rear display. An articulating display is handy, allowing you to comfortably work when your camera is set up very low or high.

While DSLR cameras are perfectly suitable for landscape photography, and many pros continue to use them, you may be wondering about DSLR vs. mirrorless cameras. As the name suggests, mirrorless cameras eschew the mirror found in DSLR cameras. This allows mirrorless cameras to be smaller and lighter, although this advantage isn’t always realized with mirrorless camera systems.

Lenses for mirrorless cameras are also generally smaller and lighter, but this is due not only to the difference in camera technology but also to recent advancements in optical technology. Mirrorless cameras typically include better autofocus area coverage, advanced features, and faster performance. They also offer a real-time live view through their electronic viewfinders, which is very useful.

All the major manufacturers have now shifted their focus to their mirrorless camera systems. However, with newness and advanced technology also comes a higher price tag. You can build a nice DSLR kit for less money and then adapt your DSLR lenses to a mirrorless camera later. If you’re in it for the long haul and have the budget, buying into a mirrorless camera system upfront is likely the better choice, but it’s not the only choice.

To summarize, the primary considerations when selecting a camera for landscape photography are image quality and, to a lesser extent, sensor size (bigger is better), durability, and usability. An excellent, fast autofocus system is a nice bonus but not a requirement. You should also survey the lenses available for cameras you’re interested in to ensure that you can purchase appropriate lenses at a price within your budget. If you’re looking to save money, look at the used market and consider older camera models that use the same image sensor as the most recent models.

Lenses Are a Critical Part of a Landscape Kit

You can have the most expensive camera with the best image sensor, but if you don’t put high-quality glass in front of the sensor, you’re leaving a lot of potential performance on the table. Fortunately, good glass for landscape photography doesn’t require breaking the bank. While pro-level lenses can easily top $2,000, that’s nothing compared to the best super-telephoto lenses that many wildlife photographers rely on that frequently cost well over $10,000. Further, as we’ll see, you don’t always need pro-level lenses.

When picking out a new landscape lens, the first significant decision is whether you want a zoom or a prime lens. Zoom lenses have a variable focal length, whereas prime lenses offer a fixed focal length. Zoom lenses have the advantage of flexibility, whereas prime lenses are often smaller, lighter, more affordable, and offer a faster maximum aperture, all else equal.

Fortunately, a fast aperture isn’t necessary for most landscape photography, so you can opt for a lighter and less expensive lens with a slower aperture. For example, a 24-70mm f/4 lens is cheaper and lighter than a 24-70mm f/2.8 lens.

While an APS-C or Micro Four Thirds camera is a viable option for landscape photography, I want to narrow the scope and discuss some of the most popular full-frame lenses. If you open a pro landscape photographer’s bag, you’re likely to find one or more of the following zoom lenses: 14-24mm f/2.8, 16-35mm f/2.8, 24-70mm f/2.8, 24-105mm f/4, 24-120mm f/4, 70-200mm f/2.8 and 100-400mm f/4.5-6.3.

In terms of prime lenses, 14mm, 18mm, 20mm, 24mm, 35mm, 50mm, 70mm, 85mm, 105mm, 150mm, and 200mm lenses all have their place.

Many of the f/2.8 zoom lenses above are available in f/4 versions, or at least there are f/4 lenses that offer similar focal lengths. Avoiding the pro-level f/2.8 lenses is a great way to save money without necessarily giving up much image quality, especially when you stop down to f/8 or slower.

If you’re interested in night sky or astrophotography, the criteria change. You no longer require autofocus since you’ll be manually focusing anyway, allowing for affordable third-party options from companies like Samyang and Rokinon. You instead care a lot about the maximum aperture. Lenses ranging from f/1.4 to f/2.8 are good choices for night sky photography. The faster, the better. When considering lenses, make sure you look up reviews specific to night sky photography because different lens aberrations, such as comatic aberration, can dramatically impact how stars are rendered.

Speaking of third-party lenses, should you consider them in general? Absolutely. Companies including Sigma, Tamron, and Tokina make high-quality lenses that are often more affordable. Sometimes they’re also entirely different from what your camera manufacturer offers. You should always research any lenses you’re interested in and read about other photographers’ experiences, but it’s well worth considering third-party options.

Not all of us have the luxury of purchasing multiple high-quality lenses for our landscape photography. So, if I could only pick just one lens or type of lens to buy, what would it be? I’d start with a 24-105mm or 24-120mm f/4 zoom lens.

Sure, it won’t be suitable for night photography, but it will work well for most landscape situations. This type of lens typically costs between $1,000 and $1,500. It’d be a 16-80mm zoom on an APS-C camera, and on Micro Four Thirds, a suitable standard zoom would be something like a 12-40mm, 14-42mm, or 12-60mm.

After adding a standard zoom to my kit, the next lens on my wish list would be a telephoto zoom lens. I’ll discuss the value of longer lenses a bit more later.

A Good Tripod is Well Worth the Investment

Don’t skimp on support. It’d be a shame to put thousands of dollars’ worth of gear onto a cheap, flimsy tripod. Or worse yet, not have a tripod at all. While plenty of landscape photographers have captured beautiful images without camera support, you’ll want to use a tripod most of the time. It’s a critical part of a complete landscape photography kit.

A good tripod is a stable tripod. Better yet, a sturdy tripod that’s lightweight and durable. If you can spend the money to purchase a high-quality tripod from a reputable brand, do it. A good tripod will outlast many cameras and lenses. It may even last a lifetime. If you can’t afford a top-of-the-line tripod, that’s okay. There are plenty of options under $250 that will keep your camera steady.

When choosing a tripod, you must first decide what material you want. Carbon fiber tripods are more robust and lighter than aluminum but often cost more money. You need to determine what weight rating you require for your equipment or equipment you might realistically purchase within the next few years. You never want to put heavier gear on your tripod than it’s designed to support. You don’t even want to cut it close, so make sure your tripod is rated for at least twice as much weight as you intend to put on it. I’ve seen people’s tripods fail; it’s not a pretty sight.

When it comes to tripod height, ideally, your tripod should be able to hold your camera at your eye level. Not every scene will work best from that height, but when it does, it’ll be comfortable to shoot if you don’t need to bend over. I prefer tripods that can go even higher, so they’ll work well on steep inclines and offer additional composition options. Likewise, it’s good if your tripod can get low, providing an exciting and dynamic perspective.

You’ll notice that some tripods include a center support column. This seems convenient but has a couple of distinct disadvantages. The setup is less stable when you extend the center column. Further, the center column prevents you from setting up low to the ground. Some tripods have designs to overcome this latter issue, but it’s still generally a good idea to avoid having a center column altogether.

You’ll need tripod legs and a tripod head. Many tripods come with a head already attached. There are a few varieties of tripod heads.

A pan-tilt head uses adjustable handles or knobs to control side-to-side and up-and-down movement. It’s a common type of tripod head, and it can work well for landscape photography. Ball-heads are often found on more expensive tripods. They have a single control that loosens or tightens the ball, which allows you to make exact adjustments in one motion. I’ve used both over the years, and a ball-head is easier to use, but a pan-tilt head won’t hold you back.

Photographers may use a third type of tripod head called a gimbal head. It balances your camera and lens and is designed for large, heavy lenses. It’s also easy to use, but gimbal heads are large, expensive, and specialized. There are also tripod heads designed for creating panoramic photography. That’s not my specialty, but dedicated equipment is worth considering if you’re serious about panoramas.

When using a tripod, keep it as level as possible. If your tripod isn’t level, it’s more likely to tip over, and that’s bad news for your camera. If you’re working near water, try to keep your tripod leg adjustments out of the water, whether they’re latches or rotating locks. This is especially important if you’re working in saltwater. Water, salt, and mud will do a number on your tripod if you’re not careful.

Wear and tear are inevitable, but cleaning your tripod, especially after being in adverse conditions, will help keep your tripod in good working order for many years. Tripods are underappreciated enough, so make sure you take good care of yours.

Essential Lens Filters for Landscape Photos

Like the trusty tripod, lens filters are an essential part of a landscape photography kit. While you can accomplish a lot when editing photos, some filter effects cannot be replicated. And even those that can are often better realized at the time of capture using a real-life filter in front of your lens.

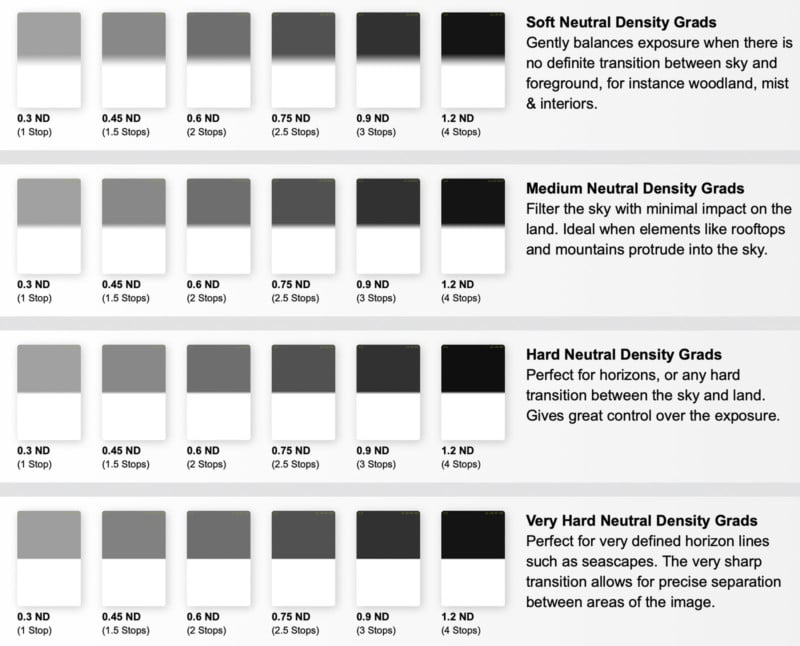

We have graduated neutral density filters thanks to landscape photography pioneer Galen Rowell. These filters are dark on one part and clear on the other. Typically, you place the darker portion over a bright sky and the clear part over a darker foreground element, which helps balance an otherwise high-contrast scene. Modern cameras have tremendous dynamic range, but even still, some scenes are too much to handle in a single exposure without a filter, especially at sunrise and sunset.

Graduated neutral density filters come in a few varieties, including hard-edged and soft-edged flavors. I opt for the latter, as they work better in any scene that doesn’t exclusively feature a straight horizon. The soft-edged filter is more practical when you introduce mountains or trees.

There are also solid neutral density filters. These are dark filters that reduce the amount of light that reaches your image sensor. If you’ve seen photos of smooth waterfalls, the photographer likely used a neutral density filter. Sometimes the ambient light is dark enough that you can achieve a slow shutter speed without an ND filter, but often, an ND filter is required.

ND filters come in many strengths. A 3, 4, 6, or 8-stop filter is a good starting place that will work across most situations. You can read more about ND filter strength here.

Perhaps no filter better illustrates what photo editing software can’t do as well as a circular polarizing filter. While the physics of a polarizing filter is beyond the scope of this article, the filter’s utility is that it reduces reflections. Whether it’s a reflection in the sky, on water, or on vegetation, a polarizing filter will help bring out a subject’s most vibrant color. They’re also instrumental for photographing waterfalls and streams, which will otherwise reflect the ambient light and look flat.

However, you must be careful when using a CPL filter on a very wide-angle lens, as they can asymmetrically affect a blue sky, causing unsightly dark spots in your image. In some cases, it’s helpful to capture two photos of a scene, one with the CPL and one without, and then blend them to get the best of both worlds.

Camera Settings and Technique

Once you have a camera, lens, tripod, and filters, it’s finally time to capture landscape photos. While making a great landscape photograph is not easy, dialing in appropriate camera settings is relatively straightforward.

Exposure Triangle

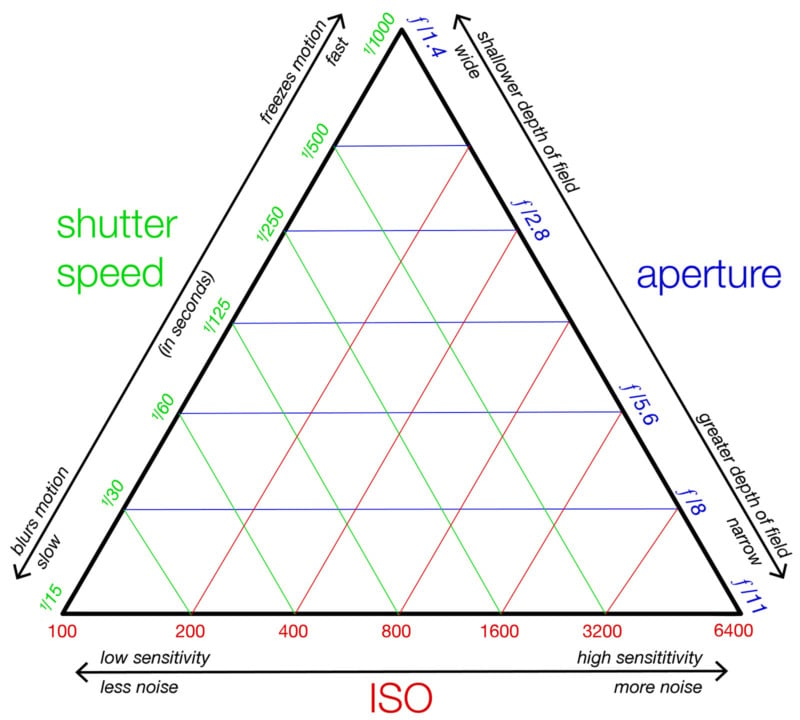

Before getting to camera settings, let’s quickly cover the exposure triangle, as it’ll inform the rest of the discussion. There are three primary components that influence your photo’s exposure. Changing any of the three settings will make an image brighter (more exposed) or darker (less exposed). The three parameters are shutter speed (the duration your shutter is open, allowing light that goes through your lens to reach your sensor), aperture (the width of the opening that lets light through the lens), and ISO (how sensitive your image sensor is to the light it receives).

For landscape photography, especially when working on a tripod, the best ISO is almost always your camera’s base native ISO. Depending on your camera, it’ll likely be ISO 64, 100, 160, or 200. At base ISO, your camera produces the best image quality with the most detail and widest dynamic range. Whenever possible, shoot at base ISO.

Aperture and Depth of Field

The primary decision you must make is what shooting mode to use. Aperture priority is good if you’re shooting a scene without much movement. This means that you will manually select an aperture, and your camera, given the ISO setting, will select the appropriate shutter speed. Aperture is crucial for landscape photography because it determines how much of a scene is in focus. The higher the f-stop, and thus the smaller the aperture opening, the more of the scene that will appear sharp. For example, at f/11, the depth of field is greater and more objects from close to far will look sharp than at f/5.6.

To make a short digression, this is as good a time as any to discuss depth of field and hyperfocal distance. In many landscape scenes, you want to get as much of the scene in focus as possible so that your image is sharp from ‘front to back.’ However, you also don’t want to stop your lens down to its minimum aperture because your image will suffer from diffraction and be soft.

We don’t need to get into the physics of optics, but the primary takeaway is that while stopping down from maximum aperture will improve quality, there comes a point when stopping down will degrade performance. There’s a balancing act between having more field depth and an acceptably sharp image. Each lens is different, so it’s wise to do some makeshift test shots with your lenses before taking real-world photos.

You can capture multiple images with different focus points and then combine them on your computer. This is commonly referred to as focus stacking. You can also use what’s called hyperfocal distance. There are plenty of calculators to determine hyperfocal distance given your camera, focal length, and desired aperture.

You can also simplify things by determining the closest object in your frame that you want to appear sharp. Then, adjust your focus until the background of the image and your selected “close” object appear similarly sharp. They may not be as sharp as possible – but they’ll appear sharp. Ultimately, how your image appears is what matters. But again, sometimes an object is so close to your camera that you simply can’t have everything appear crisp and detailed in the image. This outcome is more likely the longer your lens or, the closer an object is to the lens.

Manual Mode and Shutter Speed

Back to camera modes. Another good option is shooting in full manual mode, especially if using a mirrorless camera or a DSLR with live view capabilities. In manual mode, you choose both shutter speed and aperture.

If you’re photographing a scene with moving water, you may want to first choose a shutter speed, such as 1″ or slower, and then see how your exposure looks at different ISO and aperture settings. This is also a situation where a neutral density filter may be needed. In bright light, your camera’s ISO may not be able to get low enough for a good exposure at the desired shutter speed and aperture.

Histogram

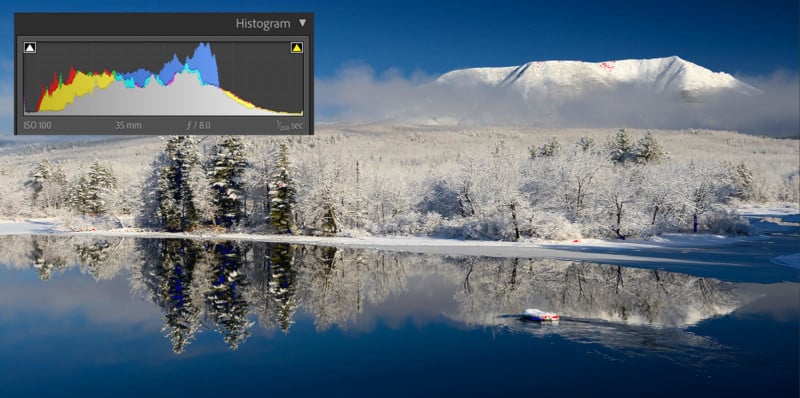

Evaluating your exposure relies upon what’s called a histogram. Many cameras allow you to see a live histogram and select camera settings as you compose a scene. A histogram is a graph that represents the tones, or levels of brightness, across your image. The leftmost edge is pure black (shadows with no detail), and the rightmost edge is pure white (highlights with no detail). Everything in between the extreme edges are pixels with information.

Your image is likely well-exposed if your histogram has the most prominent spike near the middle, with gentle slopes toward each extreme. Any big spikes at either edge indicate that you’re losing detail to shadows (left edge) or highlights (right edge). With that said, your camera shows you a histogram for a JPEG image, not raw. Raw image files allow for additional flexibility when editing photos. When processing a raw file, you can often recover some shadow or highlight detail that appears lost in a JPEG image.

Therefore, many photographers use a technique called “exposing to the right.” ETTR means that your JPEG histogram is skewed to the right, ensuring that you capture as much shadow detail as possible while having minor highlights that are easily recoverable during raw image editing. If you need to increase exposure later to bring back shadow detail, you’ll introduce noise in these areas of your image, like if you shot at a higher ISO than you did.

Every camera is slightly different regarding the flexibility of its raw files, so you’ll need to test your camera. Further, sometimes there’ll just be a highlight or shadow in your image with no detail, and that’s perfectly acceptable.

Exposure Compensation and Bracketing

Sometimes a scene is so bright in some areas and dark in others that even a graduated neutral density filter won’t do enough work. Perhaps a scene has brighter and darker elements throughout the frame, and your filter darkens or brightens areas you don’t want to be affected. In situations like this, you can use exposure bracketing. This setting allows your camera to successively capture images that are slightly brighter or darker than the rest using what’s called exposure compensation.

Your camera lets you use exposure compensation at any time, even if you aren’t using bracketing. I like to use +0.3-1.0 exposure compensation in most situations because your camera is designed to try to expose an image to what’s called ‘middle gray.’ This will make white areas appear gray rather than white. That’s typically not what we want, so don’t be afraid to use exposure compensation for times you’re not using a full manual shooting mode and your camera is making exposure decisions automatically.

Once you have bracketed images captured at different exposure settings, you can combine the images into a high dynamic range (HDR) image using software or take a more hands-on approach and do exposure blending. This will come up again in the photo editing section, but the gist is that you can achieve a wider dynamic range using multiple photos shot with different exposure settings than a single image.

What is a Raw Image?

If you’re a beginner, you might be wondering, “what is a raw image?” Nearly every camera, and even most smartphones, lets you capture a raw image file. A raw image file includes minimally processed data from your camera’s image sensor that must then be processed by a raw converter, such as Adobe Lightroom, to display in a usable color space. Raw image files have much more flexibility than JPEGs, allowing you to extract more detail, color, and tonality than would otherwise be possible.

You should always shoot landscape images in raw. If you want to shoot raw + JPEG, that’s fine, but make sure you’re shooting raw images at the highest quality and largest size your camera allows. There’s a lot of debate about uncompressed versus compressed raw file quality. We don’t need to solve that debate, but you should at least choose a lossless compressed option.

![]()

Other Camera Settings to Understand

Other camera settings to consider include white balance, long exposure noise reduction, high ISO noise reduction, lens corrections, and autofocus mode. For white balance, I recommend using automatic. You can easily adjust the white balance when processing your raw image files later, but automatic will often be a great starting point.

As for noise reduction settings, I leave in-camera noise reduction disabled. I prefer to perform noise reduction when editing images. Lens corrections are okay to leave on, but again, it’s often better to perform these yourself. Most cameras and lenses have available correction profiles in many photo editors, and these are typically better than corrections performed in-camera.

![]()

Focus Modes

Autofocus is a big question for many photographers. Your subject will almost always be stationary when doing landscape photography, so you want to use AF-S or Single-Shot AF. The terminology varies by camera brand.

For the autofocus area, I prefer using a single-point setting that you can move around the frame as needed. Don’t let your camera determine your photo’s subject. While autofocus systems are incredible, you have the time to exercise control.

Speaking of time, take the time to zoom in on your image to ensure that it’s in focus. If the light is low, such as when shooting in the early morning or after sunset, don’t be afraid to switch to manual focus. Again, zoom in and check the focus. I always manually focus when zoomed in with live view.

Using Your Camera’s Self-Timer or Remote

There’s one more setting I want to discuss, self-timer. While I recommend using a wireless or wired remote to control your shutter for landscape photography, your camera’s self-timer will do in a pinch. Using the self-timer ensures that you aren’t touching your camera when the shutter opens, eliminating the risk of camera shake. This is especially important when doing long exposures. Most cameras default to 5 or 10 seconds of delay when using the self-timer, which is too long for our purposes, so switch it to 1 to 3 seconds so that you’ll be able to shoot more images. 10-second delays add up.

Composition in Landscape Photography

You can capture an image with perfect exposure and tack-sharp focus, but it won’t be a good photo if it’s not well-composed. It’ll be competent on a technical level, but not an artistic one.

In this section, I’ll discuss different aspects of composition that are worth considering. Not every rule or guideline should be applied in every situation. However, these tips are worth thinking about when in the field or when cropping your landscape photos.

![]()

But before getting into the tips, it’s worth mentioning the importance of identifying your subject. Every photographer has been guilty of taking a photo of nothing at one time or another. A beautiful scene may appear to be a worthwhile image all by itself, but that’s rarely true. Good composition requires identifying a subject. Everything flows from that crucial first decision.

Rule of Thirds

Most of the time, putting your subject dead center in the frame is a bad idea. It rarely works in landscape photography. Placing your subject off-center often makes an image more interesting. If you’re unsure where to put your subject, the classic “rule of thirds” is a good option. What’s great about this rule is that it works well in many situations and an available viewfinder overlay in most cameras and the default cropping frame in most photo editing applications.

Curves

Curves are a helpful way to lead the viewer’s eyes through the frame. If I come across a potential curve in a landscape scene, it’s exciting. Rural roads, winding streams, or even how light hits objects in your photo can create visual curves. Ultimately, the goal is to keep your viewer engaged, and there are few compositional elements better at this than curves.

Straight Lines

Straight lines are also great, especially when you create compositions with parallel or perpendicular lines. Parallel lines create nice symmetry in your scene, whereas perpendicular lines show more dynamism and power. Like curves, these don’t need to be prominent lines that knock the viewer over the head. They can be subtle, like slight differences in color or brightness. Using curves or straight lines as leading lines into your frame and toward your subject is ideal. Diagonal lines are also excellent compositional elements.

Balance

Compositional balance is vital. Balance can be achieved in many ways, including through symmetry–like reflections, by balancing light and dark areas of your frame and balancing color. To put it simply, you don’t want your image to be weighted heavily toward one side. Sometimes I like to apply a temporary blur to an image when editing to see how an image’s balance is shaping up. Removing the detail helps me see how the image looks only in terms of tonal values and color. If my eyes are drawn to a specific area, I need to see if that’s where I want the viewer’s attention to go.

Watch Your Edges

This is a big one. You don’t want your subject cut off by the edge of the frame. If there’s a single element or small group, like a tree or a patch of flowers, try to keep them in the frame and away from the edge. When setting up a scene, you may become too focused on composing your subject that you lose track of the rest of the image. Before taking a shot, I constantly scan the very edge of the viewfinder or monitor to check if there’s anything that I’ve cut off or something distracting. Give your subject room to breathe and exist within your composition.

Don’t Be Afraid to Get Closer

If there are unnecessary or distracting elements near the edge of your shot, consider moving closer or zooming in. Most of the time, a first composition includes too much rather than not enough – too much sky, too much water, too much foreground, etc.

Foreground and Depth

Speaking of too much foreground, that’s not to say you shouldn’t include foreground in your landscape photos. Not every scene works best with a layered composition, but many do. A great way to create layers and depth in a scene is to utilize foreground elements. One of the first things I do when I get to a new place is to look around for anything I can use as an interesting foreground. It may be a rock, flowers, or a puddle. By incorporating something close to the lens, you create a sense of scale in your photo, and there’s more for the viewer to explore.

There is No Such Thing as Going Too Wide

If you’re using foreground elements in your composition, you may be tempted to use an ultra-wide-angle lens. Ultra-wide lenses are great for capturing more of a scene and delivering exciting perspectives. However, they can also make a big, impressive background look smaller relative to objects closer to the lens. Perspective is important to keep in mind. You don’t want an imposing mountain to look like a small bump on the horizon.

Portrait Orientation for Landscape Photos

“Landscape orientation” doesn’t mean you can’t photograph landscapes vertically. The default orientation of your camera is horizontal, which is sometimes called “landscape” orientation. Don’t let that fool you; shooting vertically is always an option. Not every scene works best vertically, but it’s a great idea to consider “portrait” orientation compositions.

![]()

Keeping It Simple

The design principle to “keep it simple, stupid” is well-applied to photography. Some of your favorite landscape photographs may seem complex, but they’re almost always simple when boiled down. Your image doesn’t need to do a lot to be effective. It needs to be interesting, and ultimately, being interesting rarely requires complexity. If something in your frame isn’t doing the all-important work of assisting your subject, consider eliminating it from the frame altogether. Or, at the very least, make sure that it’s not a distraction. A strong composition is a simple one.

![]()

Colors

You could write a book about colors. Many have. When composing landscape photos, the bare minimum to consider about color is to think about how tones interact with one another and how different colors have more “weight” in a composition.

If you think back to art class in elementary school, complementary colors are the big ones to consider. Blue and orange complement each other, as do red and green. These aren’t unusual in nature, and these color combos play well off each other and contribute to a dynamic composition.

It’s also important to think about how color affects the emotion of an image. Blue can be calming, red is louder and demands more attention, orange creates a sense of warmth, and yellow is bright and energetic, just to name a few. Adjustments to the color temperature of a scene, making it cooler or warmer, can dramatically affect the emotion of your image.

Keep Things Level

Do your best to keep your camera level when capturing landscape photos. Many cameras include a built-in level. You can also buy a small level to put in your camera’s hot shoe. No matter how you level your camera, just make sure you do it. A crooked horizon is distracting, and fixing it when editing will require you to cut off part of your image.

![]()

A Summary of Composition

There’s so much more to say about composition, and it’s a skill you’ll spend the rest of your life working to improve. However, suppose you’re just getting started, and you feel overwhelmed. In that case, the three most significant compositional ideas always to remember are understanding your subject, arranging the frame to emphasize the subject while cutting out anything distracting, and keeping your image simple. The rest will sort of fall into place as you go.

Basic Photo Editing for Landscapes

Sometimes it can feel like learning how to edit photos is even more complicated than learning to take good pictures in the first place. I will keep things relatively simple here because you will rarely need to spend a lot of time editing photos if you use good camera techniques and filters. There’s also no need to get bogged down by which editing application you use. Many photo editors will do the trick. But, if you have no idea where to start, the Adobe Photography Plan is $10 a month and includes Adobe Lightroom and Photoshop, two of the most popular photo editing applications. There are a lot of great educational resources for Adobe software.

It’s also a good idea to ensure that your monitor is calibrated. It’s probably unnecessary to purchase a new monitor, but if you’re interested in upgrading your monitor, check out our Best Monitors for Photography and Photo Editing roundup. A good, calibrated monitor will improve your photo editing workflow and is especially helpful when you start printing images.

Cropping

When you open your landscape image in an editing application, you should first ensure that available camera and lens profile corrections are applied. This is especially important with wide-angle shots, as these lenses are more likely to exhibit distortion.

Next, consider cropping. Ideally, you spent time in the field and captured the perfect composition. However, sometimes you need to adjust the composition after the fact. There’s nothing wrong with cropping to improve composition. There’s also no reason against using a different aspect ratio than your image sensor. Just because your camera shoots 3:2 or 4:3 images doesn’t mean that you must stick with that aspect ratio, especially if you intend to print your photos.

Global Adjustments

Assuming you have been shooting in raw, which you absolutely should be doing, you have a lot of flexibility for the rest of your post-processing workflow, especially with white balance. Automatic white balance does a great job, but you may want to change it slightly to better reflect what the scene looked like at the time, color cast and all, or you may want to change the emotion of your shot by making it cooler or warmer. When you shoot raw, the world is your oyster when it comes to white balance, so experiment.

After cropping and adjusting the white balance, now is an excellent time to check in on your histogram. Your raw image’s histogram may look slightly different than the one you saw on the back of your camera. Remember, you typically want your histogram when editing to be balanced, meaning your photo has a full range of tones.

You can adjust your image using sliders, like exposure, brightness, contrast, shadows, highlights, blacks, and whites. You can also use curves adjustments. I prefer using curves, but sliders are more straightforward and often deliver good results. With each adjustment you make, check on your histogram and pay close attention to the image quality of the shadow and highlight regions of your image. As with any adjustments, a light touch is often best.

![]()

You can also adjust individual colors and the overall saturation of your image. Perhaps you want to emphasize a particular color harmony in your photo or draw attention to specific colors. I typically focus on a few colors in a scene, often green, blue, and orange. These are common colors in a landscape photo, at least where I most often shoot, and a slight increase in the saturation or brightness of these colors will provide more “punch” to a landscape photo. Like with adjustments to brightness, it’s easy to overdo it, so making minor adjustments is the best practice.

Local Adjustments

So far, we’ve discussed what are called “global” adjustments. These adjustments apply to your entire image. There are also “local” adjustments. These are powerful ways to put the finishing touches on your image because they are specifically applied to only certain parts, colors, or tonal values in your photo.

While there’s no limit to what you can do to your photos, common local adjustments include using adjustment brushes and virtual graduated filters. Like the latest version of Adobe Lightroom Classic, some apps have AI technology to select and mask the sky in photos automatically. This allows you to adjust the exposure, color, and much more of your sky without affecting the rest of your image.

There are different ways to make local adjustments beyond filters, brushes, and automatic masks. Most photo editors also allow you to select a specific color or luminance range. This means that you can choose an area of the image that’s a particular color or brightness and edit only those pixels. These pixel-level masks are precise in a way that manual masking selections never will be.

Sharpening

There’s no perfect recipe for success when sharpening, as images from different cameras will look best with varying sharpening strengths. View your image at 100% in your photo editor when sharpening photos. You want your image to look sharp and detailed, but you’ll introduce artifacts and noise if you overdo sharpening. There’s a fine line between an image looking detailed and appearing artificial.

You can also utilize local adjustment techniques and masks to sharpen only areas in your image with detail, like mountains and trees, rather than the entire photo, including the sky, which likely doesn’t have any detail you want to sharpen. I typically employ a light touch with sharpening and recommend you do the same.

![]()

Special Technique: Focus Stacking

Earlier, I mentioned that it’s not always possible to get enough depth of field with a single frame, especially when you’re photographing with a longer lens or including close foreground elements. This is where focus stacking comes in handy. To focus stack images, you must first capture multiple images with different focus distances. Ideally, the files have identical, or at least very similar, exposures. A manual shooting mode can be helpful here.

Once you have your images, you can load them into software like Photoshop or Helicon Focus. I typically use Photoshop and then load my focus stacking images as layers. I go to Edit > Auto-Align Layers > Auto. At this point, you have two choices. You can go to Edit > Auto-Blend Layers > Stack Images. This should work well in many situations. You can create layer masks and manually stack your photos if it doesn’t. Helicon Focus is also an excellent automated solution.

This is just a general outline of focus stacking, but it’s a vast topic. This step-by-step focus stacking guide is an excellent resource if you want to try out more advanced stacking techniques.

A Summary of Editing

Ultimately, what matters most isn’t the histogram or any sliders or settings, it’s how you feel about your photo. If you like the way it looks, you did an excellent job with the editing. However, a few final words on photo editing. You want to use non-destructive editing techniques. Many photo editing apps operate like this by default, but it’s important to preserve your original raw image files. Like your photo editing skills, your editing skills will improve with practice, too, and you may want to revisit old images years later. To that end, back up all your original image files.

Planning Your Landscape Shots

The Best Time of Day for Landscape Photography

You can capture great landscape photos at any time, but many landscape photographers prefer the early morning or the late afternoon and early evening. I captured most of my favorite shots within an hour of sunrise or sunset.

I prefer sunrise because there are almost always fewer people around, and I still have the rest of the day ahead of me when I get done shooting. It’s a great way to kickstart a day.

Scouting Locations

Sunset shooting has a distinct advantage, though. You can show up at a location in the afternoon and scout it in full light before sunset. Scouting locations is important because it lets you plan potential images ahead of time, and you can test out different compositions while the light isn’t that good, ensuring that you’re ready when – or if – the conditions work out well.

Some locations work best at sunrise and not sunset, or vice versa, because of how the light hits the scene. Scouting helps you get a sense of this, but you can also use apps like PhotoPills to plan your shots and see how the sun will interact with a given location. PhotoPills is also great for other information like sunrise/sunset and moonrise/moonset times, calculating exposure with different filters, calculating depth of field, and much more.

Seasons

As for seasons, this depends heavily upon the location. Some beautiful areas aren’t accessible year-round, so that’s something to consider. Seasonal weather patterns can significantly impact how a place looks, too. Generally, I like every season but summer. There’s nothing wrong with summer, but if you’re as far north as I am, summer means extremely early sunrises and very late sunsets, making getting up early even more challenging. Summer also means humidity, which frequently causes hazy conditions.

The Importance of Preparation

All these unknown factors demonstrate the necessity of scouting and researching locations. There’s no substitute for being at a location, but the value of researching from home is not to be understated, either. If you’re planning a specific trip for landscape photography, especially if it’s an expensive one, dedicate as much time as possible to planning out different areas you want to visit and deciding when you think those areas will be best concerning time of day and weather.

Landscape photography may seem like a slow-paced endeavor, but there are times when good light fades extremely fast, and the more prepared you are ahead of time, the better your chances of success.

Handling Failure as a Landscape Photographer

You can do everything right – make all the best plans, do extensive research, and compose the perfect shot in the field – and the good light never arrives. You go home empty-handed. It’s frustrating and, unfortunately, inevitable. If you spend a lot of time doing landscape photography, you’ll quickly find that the mediocre and bad days vastly outnumber the great ones.

It’s easier said than done, but you must try to find the silver lining. Even if good photo conditions don’t materialize, you should still be able to do valuable scouting and grab some fresh intel about a location. I like to make notes on my phone, especially when visiting a new spot. Even if I don’t get any good photos, I at least learn something and give myself a better chance of making a good image the next time.

It’s also an opportunity to try a different style of photography. Maybe the conditions aren’t good for the shot you envisioned and hoped to capture, but they may be okay for other types of images. You can try switching lenses, heading to a nearby spot, or trying different techniques like long exposure photography. Sometimes flat light can work quite well for long-exposure photos or even for black and white landscapes, depending upon the scene.

Final Words

Landscape photography is incredible. It’s a great – and accessible – way to enhance your enjoyment of the outdoors and improve your overall photography skills. It’s a rewarding blend of preparation, skill, and luck. There’s not much more thrilling than when all the pieces come together, and you make a beautiful landscape photograph.

![]()

I hope that this guide offered you some helpful tips for either trying landscape photography for the first time or improving your existing skills. Ultimately, there’s no substitute for getting out there and capturing photos. Happy shooting, and may the light be ever in your favor.

About the author: Jeremy Gray is a photographer and writer based in Maine. You can find more of his work on his website.

Image credits: All photographs, unless otherwise noted, by Jeremy Gray.