Panasonic, The Lumbering Tech Giant That Makes Cameras

![]()

The camera sector isn’t exactly a thriving business at the moment, with year-on-year declining sales and a slew of manufacturers having exited the market.

An Overview of the Company

Panasonic, known as Matsushita up until 2008, is not a small company, with a turnover of ~$65 billion (in 2021) and employing some 260,000 people. Its principal focus is on home appliances, which include consumer electronics, manufacturing in large volumes equipment such as kitchen appliances, refrigeration, displays (projectors and TVs), DVDs, PCs, and cameras. However, Panasonic also designs and sells into the specialist avionics, automotive, and industrial markets.

The company’s cameras fall within the much larger Appliances Division which makes up 37% of income, although other large divisions include Life Solutions (22%), Automotive (20%), and Industrial (19%). For Panasonic, 2021 saw a modest reduction in sales (11%) and operating profit (12%), although the Appliances Division saw a smaller drop in sales (4%) but an increase in operating profit (8%).

Beyond this general overarching view of the business, it’s almost impossible to get any meaningful information on Panasonic’s cameras; if you look through its 2021 financial report, cameras are not even mentioned while disaggregating its sales is difficult as the company doesn’t talk about cameras (let alone sales volumes!) and the only other primary metric is from the BCN Awards Data. Panasonic doesn’t feature in the three main categories (mirrorless, DSLR, integrated), though it steamrollered the video camera award, taking 43.6% of sales followed by Sony (26.3%) and DJI (11.2%). However, this isn’t a product category for CIPA so we don’t know how many global shipments they represent.

The only other recent data point we have is from the Techno System Research marketing report for 2020 (as reported by Fuji Rumors), which confirms global camera shipments at 8.9 million units with the following market share: Canon (47.9%), Sony (22.1%), Nikon (13.7%), Fuji (5.6%), and Panasonic (4.4%).

Of course, this combines mirrorless, DSLR, and integrated cameras; the report then focuses on the mirrorless segment, with market shares changing to: Sony (35.7%), Canon (32.6%), Fuji (11.8%), Nikon (8.0%), Olympus (6.4%), and Panasonic (5.5%). Linking this up with global shipment data from CIPA, Panasonic’s share equates to about 157,000 units, only hair’s width back from Olympus and Nikon.

Where Has Panasonic Come From?

Panasonic’s camera business is largely predicated on the digital revolution, though, much like Sony, it was manufacturing video cameras back in the 1980s and had expertise in lens design. Back in the dust-covered history of film cameras, it did actually make some models, though they were bottom shelf, point-and-click, affairs such as the C-225EF.

As the 1990s progressed, it gradually introduced more sophisticated electronics such as autofocus and super-zooms. At the same time, it was also developing early compact digital models such as the PV-DC1000 and NV-DCF1 (both in 1997). However, it was the pivot to digital that saw a step-change in the manufacturing it undertook, which was largely built upon the corporate relationships it forged. Two stand out that have stood the test of time: Leica and Olympus.

![]()

Panasonic was presumably the manufacturer of the 1995 Leica Minilux before the foundation of the Lumix series of compact cameras in 2001, for which Leica allowed the use of its lens constructions but left the design and manufacture (subject to approval) to Panasonic. In return, Panasonic focused upon camera electronics. This was similar to the relationship Leica had with Minolta in the 1970s, but this time it was trying to reforge itself as the digital era dawned.

The LC5 and F7 were the first fruits of this labor and marked a step up from Panasonic’s previous offerings; it was the right relationship, at the right time, just as digital camera sales exploded.

Panasonic wasn’t standing still, though, as it tried to strike out in a direction that was different from Nikon, Canon, and Sony (which had just acquired the well-established Minolta). Olympus offered an alternative route through its Four Thirds System collaboration with Kodak. Olympus had singularly failed to pivot to a digital SLR from its successful line of OM film cameras and the Four Thirds was a second bite at the apple, except this time doing something intentionally different to other manufacturers and that wasn’t APS-C or full frame.

The E-1 was Olympus’s first offering that introduced a new sensor size and lens mount, starting a fresh system from scratch. Kodak was now in the sunset of the digital day and would soon fade to obscurity, but it supplied the first sensors before Panasonic filled the manufacturing gap in later Olympus models. In the end, only Panasonic (and as a result Leica) and Olympus made camera bodies for the Four Thirds ecosystem.

The E-1 was a revolutionary flop; the 2x crop factor of the Four Thirds specification gave cameras reach and, with the smaller files, potentially speed. It also meant they could be both smaller and lighter. Olympus produced the E-1 for news and sports shooters, but ultimately it wasn’t keenly enough priced and had relatively slow shooting speeds and AF compared to Canon and Nikon.

Panasonic, however, had joined the party and released its first-ever DSLR in the form of the L1 in 2006. The L1 and its successor, the L10, were Panasonic’s only Four Thirds cameras as the brand pressed ahead with the development of the Micro Four Thirds (MFT) system. Who knows who came up with the idea, but perhaps Panasonic’s video credentials were the driver behind removing the mirror box; this gave more video-like performance and saved space and weight, however, the downside was that it now relied on contrast focusing, a technique in its infancy.

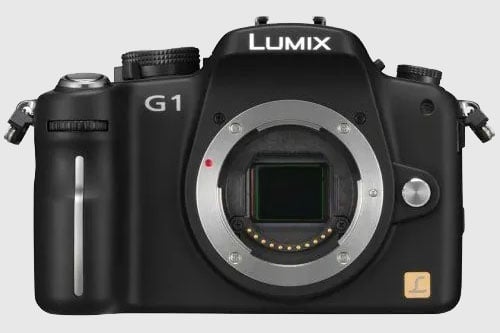

Panasonic was the first to the manufacturing punch with the release of the G1 in 2008, followed — in time — by the Olympus Pen E-P1. While it would take Olympus until 2012 with the release of the OM-D E5 to really innovate, Panasonic had nailed its intentions to the mast from day one. Video was king and there was a burgeoning market of amateur (and not so amateur) videographers wanting the product.

Panasonic had healthy sales from day one and had the number one spot in BCN mirrorless at 38.7% in 2011 when the category first appeared (and likely from 2008). It wasn’t until the release of the OM-D E-M5 in 2012 that Olympus finally overtook it. Perhaps Panasonic saw the writing on the wall at this point, whether it was the need to sell both small and large sensors or that Olympus was solely committed to MFT, but it decided to produce full-frame models in the form of the S1 and S1R in 2019. This obviously came from its relationship with Leica; the L-mount first appeared on Leica’s 2014 Leica T and is a thoroughly modern mirrorless mount designed for full-frame.

Was this part of Panasonic’s strategy, did Leica require Panasonic to produce a full-frame model as part of their strategic partnership, or was it simply an opportunity that presented itself? Whatever the reason, Panasonic now finds itself with an enviable range of MFT cameras that are compact and particularly good at video. These are accompanied by a high-performance full-frame camera that shares a heritage with Leica and has a growing range of native lenses.

There is now both breadth and depth to its offerings.

Does Panasonic Have a Clever Long-Term Plan?

The wider question is this: does Panasonic — in its development from bottom-of-the-bin film cameras through to high-performance full-frame cameras — have a clever long-term plan? Or are cameras simply a corporate plaything supported and cross-subsidized by the wider business?

Firstly, Panasonic doesn’t have a long camera heritage like Canon or Nikon; there is obvious pride in its products, but it isn’t the cultural cornerstone of the business.

Secondly, it has been constant in its pursuit of success and market share from its early partnership with Leica.

Thirdly, it hasn’t been afraid to innovate within the constraints of the partnerships it has formed. Canon, Nikon, and Sony have all been singularly focused on their own systems and, in their own ways, conservative (although perhaps less so with Sony).

Have developments in Four Thirds, MFT, and full-frame simply been a case of being in the right at the right time, or has Panasonic been slowly building breadth and depth as capacity and capability have increased? It recently committed to continuing the breadth of its MFT offerings.

Flipping this line of thinking on its head, was full-frame a “done deal” from the beginning? Was there always a plan to produce a large sensor model in collaboration with Leica as both companies developed in tandem? Are we seeing the fruits of that strategy as we enter the 2020s?

Is Panasonic going to increase its market presence, building out its full-frame lineup as part of the L-Mount Alliance with Leica and Sigma? Or is all we are seeing a haphazard approach to its product line development? If the L-Mount isn’t successful, will it pull the product range to continue its focus on Micro Four Thirds?

In short, is Panasonic lumbering or slumbering?

Image credits: Panasonic GH5 photo and figure illustration from Depositphotos