Martin Parr: Photographer of Leisure Pursuits of the Wealthy Classes

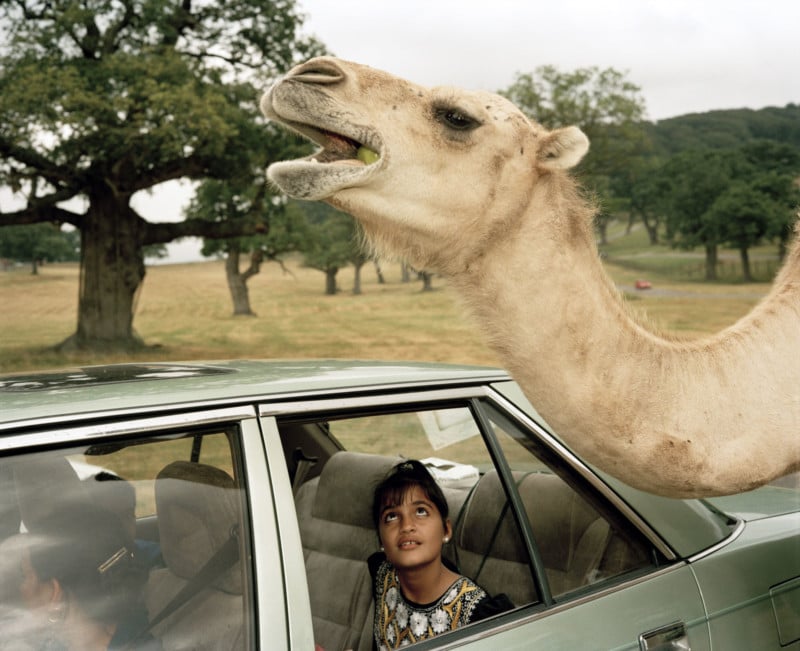

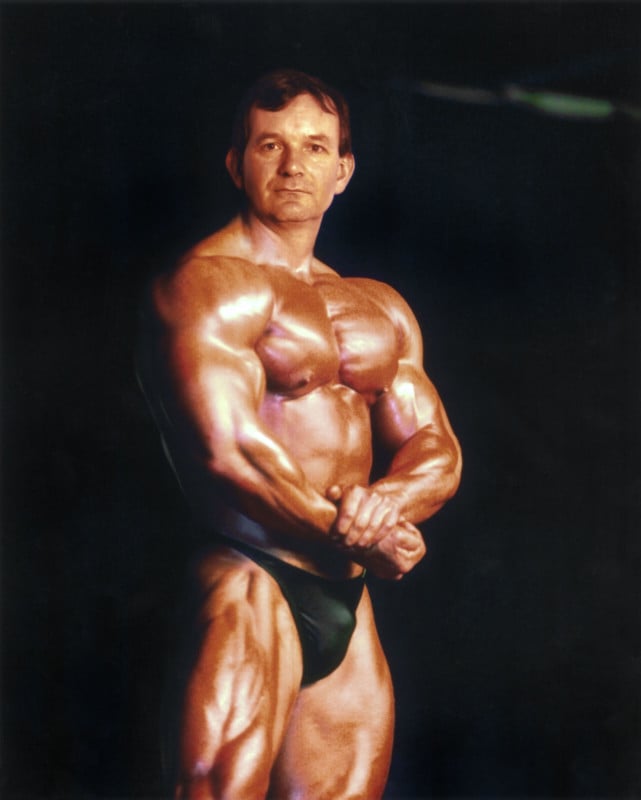

For five decades, British documentary photographer Martin Parr has shown us the world from his unique perspective but saturated with color and contrast. Most of his subjects are at leisure – relaxing, eating, or having a good time.

“I’ve been a photographer for over 50 years,” Parr tells PetaPixel. “I’m trying to work out my relationship to the world; of course, the biggest plan in my world is where I live in the United Kingdom, so that’s become quite a priority. I’m a photographer who likes to do other things like curating, making films, radio, and starting a foundation.

“But ultimately, my core activity is looking at the leisure pursuits of the wealthy classes, in particular, I guess, more than anything else, not only in the UK but also around the world.”

Photojournalist or Documentary Photographer?

Parr has been referred to as a documentary photographer and photojournalist by Wikipedia, but he prefers documentary between the two labels often ascribed to him.

“I don’t see myself as a photojournalist,” says Parr. “I see them rushing off to, you know, wars and famines and all the other nasty things in the world that we need to know about through photography and film, but it doesn’t interest me to do that… I mean, it’s about recording the world and your relationship to it, so yeah, you could argue there are a lot of documentary pictures on Instagram. Documentary is a wide platform these days.

“We’ve just done a book with Gerry Badger, Another Country: British Documentary Photography Since 1945, on the history of documentary photography in Britain. Some of those you could go through and say, that’s not documentary, so I’d say it’s a wide platform, and it needs to be.”

Parr feels that documentary and street photography overlap. His work has also been featured in street photography books, and the two can be the same.

“I don’t worry about these definitions because I’m worried about taking the picture, not how to define it,” he says.

Parr works in urban as well as rural settings, but cities are better for his work.

“I’ve done photographs in rural places, but guess I’m interested in people, and there are more people in urban places than in the rural,” Parr reasons. “I’d say there is [satire]; I mean one thing, one of the few things we’re very good at still in Britain is a sense of humor. We have quite good comedy on television, so I think of myself as part of that tradition.

“I’m very democratic in my photography. I’ve done the working class, the middle class, and the upper class. I don’t mind what class you give me. I’m very happy to photograph them. I’m interested in photographing the social classes of England. That’s my biggest project, but remember, I’m very widely traveled. I’ve been all around the world with photographic projects, commissions, and cultural commissions.

“I came to the Trump Republican rally — the convention, and I did a book called Conventional Photography (2017). It was quite amazing to be amongst the Republicans. It doesn’t take much to tell you that they’re more photogenic than the Democrats.”

Parr mostly has people in his pictures, but he has done one landscape book – Remote Scottish Postboxes. Between 2004 and 2010, Parr and his wife holidayed on the Scottish mainland, frequently stopping to photograph local mailboxes against the lonely yet beautiful Scottish backdrop.

The American Influence on Color (and Medium Format)

In the early 1980s, Parr decided to move to color from black-and-white photography.

“First I saw [the work of] all the photographers coming from America like Stephen Shore, William Eggleston, Joel Meyerowitz,” remembers Parr. “It was inspiring to see Sally Eauclaire travel to the UK with her book The New Color Photography, which we all liked and went to see her and hear her talk. Also, I’ve been collecting postcards around the John Hinde theme, very brash bright postcards, and I thought, let’s just try color [in the early 1980s.]”

“I’ve always been fascinated by people’s heads. I was taking pictures of people in hats from behind, by myself, when suddenly this guy appeared with a bald patch. I followed him down the street. I don’t think he noticed. Rear views are something I specialize in, but this was one of my best ever: a perfect hat and a perfect bald patch. It illustrates the battle between hope and reality, the human spirit encapsulated in the back of a man’s head.” — Martin Parr

In 1982 when Parr moved back from Ireland. He picked up the recently introduced Plaubel Makina 67 and started shooting color. His wife worked in Ireland as a speech therapist for two years, so they moved there. While there, he also did a book, A Fair Day-Photographs From the West of Ireland.

“During the years of doing the 67 medium format, I used flash quite a lot,” says the documentary photographer. “[The colors] are quite brightly intense, and I like the brashness of that palette, so I was quite happy to adopt. These days I still have a flash gun, but I don’t use it quite as much, but I have a classic Gary Fong [diffuser] on top of the 5D if I need it.”

Parr did a project called Bad Weather in which he used flash, but he does not in most of his B&W creations.

Henri Cartier-Bresson was not Impressed

The founder of Magnum Photos, Henri Cartier-Bresson, visited Parr’s exhibition in Paris around 1994, and the legendary “decisive moment” photographer was not impressed.

“It’s the color that he did not like,” remembers Parr. “Cartier Bresson said, ‘It looks like you’re from another planet.’ He was quite crossed about the show, so I wrote back to him, ‘I understand how you feel, but why shoot the messenger.’

“Now, what’s interesting, though, is that I’m doing a book with Cartier-Bresson in four weeks. Very few photographers [get to] do a book with Cartier-Bresson. He came to England in the 60s and made a film for ITV about the north of England and Blackpool, the biggest resorts up there.

“This film, he didn’t much like because they were zooming in and out. He supplied his stills, but the stills from that project got hidden away. François Hébel, director of the Henry Cartier Bresson Foundation, who’s about to leave, decided to do an exhibition in his new gallery space in the basement of us two together, and the show is called Reconciliation. There’s a book published with both of our photos in it.

“Martine Franck [Cartier-Bresson’s second wife and Magnum photographer] came in and was very keen for us to sort of make-up. She invited me to lunch, and we got on. Since that moment, we got on fine; we weren’t great friends, but we were civil and said hello to each other, and I got him to sign all my Bresson books. So, it wasn’t an issue, but I think it’s a great title for the show called Reconciliation.”

The Museums Don’t Want Color

In the 1970s, photographers who wanted to be taken seriously and display their work in museums needed to work in B&W, Parr told TIME magazine. At that time, color was the palette of commercial photography and snapshot photography.

When reminded about this statement, Parr says, “Well, basically yes, but a bit out of date because in the 60s you could be a serious color photographer like Eggleston in the 1976 [MOMA, New York] show.

“As you know, it’s pretty much true, but nowadays, what’s interesting when we look back, no one blinks an eye, whether it’s color or B&W. When it was first introduced, it was almost like Bob Dylan going electric — it was really regarded as being heresy. In New York, Eggleston was actually lambasted by all critics. It was probably the most reviled show of the decade.”

The Problems of Getting into Magnum Photos

“Philip Jones Griffiths [his book on the Vietnam War, Vietnam Inc., crystallized public opinion and gave form to Western misgivings about American involvement in Vietnam] was my main enemy,” says Parr. “He tried desperately to stop me from being part of Magnum, but he failed. It’s the traditional photographers that objected.

“You know the system in Magnum; you put your folio forward to become a nominee, you need 50% of the votes from the very first instance…I was never in the room, of course, but I knew what was going on.

“The arguments have never been more bitter, demanding, and loud than discussing my work and whether I should be going up the scale or thrown out of Magnum.”

Parr became a member of the prestigious photography cooperative by one vote and joined in 1994.

“And then ironically, of course, I was president of Magnum for three and a half years from 2014-2017,” he says.

The Controversial Photographer?

Parr’s work has been the focus of various criticisms and controversies throughout his decades in the industry.

“There’s plenty of it,” says the photographer. “I’m controversial. It still amazes me that I’m controversial. How can someone go to a supermarket and take pictures or to a beach resort and be controversial, and people who go to war and famine and photograph people dying and no one thinks that’s unethical? That’s a surprise of it all.”

To Parr, one of the main issues is the “truth” of what is seen in photographs.

“Most of the photographs in your paper, unless they are hard news, are lies,” Parr told The Telegraph. “Fashion pictures show people looking glamorous. Travel pictures show a place looking at its best, with nothing to do with reality. On the cookery pages, the food always looks amazing, right? Most of the pictures we consume are propaganda.”

“I still agree with that. I mean, here’s a simple illustration if you go to a supermarket and pick a cold pie or something like that. Look at the picture on the cover [of the packaging], and then you look at what’s inside — they very rarely look the same, they never look the same.”

In 2010, The Telegraph described Parr as “an internationally renowned photographer, recognized for his oblique approach to social documentary…”

“I am not sure I would actually describe it as oblique,” says Parr with a shrug. “I mean, I just have ideas; I go to different events, I want to photograph them, and if you call them oblique, I’m quite happy because that’s an unusual name that I can’t think that’s been applied. Maybe another lie, but I am trying to capture my relationship with the world through photography.

You know The Telegraph is the second most right-wing paper in the UK… There will be more about me in The Guardian, the classic left-of-center paper that my colleagues and I read.”

A Wide Focal Range of Photo Interests

Parr both loves the United Kingdom and hates it, and sometimes within the same frame.

“Well, I certainly do because I was very pissed off about my compatriots voting for Brexit, so it heightens attention that I’m trying to find in the work that I take,” admits the Bristol-based photographer. “So, yeah, any contradictions, any ambiguities are welcome.”

Parr likes to get close to his subjects even in today’s times when people are more suspicious than in the past.

“When I’m photographing a person, I’ll ask them automatically unless I’m photographing their neck or back,” the documentarian says. “If I’m photographing someone’s hand, you know I couldn’t do it without asking, so I just ask.

“It’s something [regular street photography] you have to get used to. You can still do it; it just means you have to do it even more, and you have to do it with more determination than before because it has become a bit more difficult.”

Parr’s mantra is that no one will pay any attention unless you make an entertaining picture.

“That’s part of what I try and do is to make a picture that can draw people in and then if they want, if they look at them all together because obviously, you present sets rather than one picture on its own,” says Parr. “There is something to be read about the politics of what’s going on, but it’s not mandatory.

“I did photograph the Queen but from behind, and that’s one of my best pictures of recent years. There are very few people you’d recognize from behind.”

He would have liked to photograph the Queen in a one-on-one session, but “I would have been seen as too wild for the Queen.”

Another subject that Parr has turned his camera lens on is food.

“When I got the macro lens [Nikon], I was very excited about taking pictures with this, and food was one of my first subjects,” the photographer says. “I tried to find the worst example of food in England, France, Germany, and Europe. Bad food makes good pictures. It makes better pictures than good food. I have also been to state fairs in America where the junk food is even more heightened than in England because it’s more of it and more people are eating it.”

Over 100 Photobooks and Counting

Parr has published about 120 photobooks, but that impressive number is still far from being a record in the photo industry.

“I mean, the Japanese are so ahead of me,” Parr sighs. “It’s like Araki [Nobuyoshi Araki (b. 1940), the most prolific Japanese photographer] must be 475 now and Daido Moriyama about 300. I might get in the top five in the European chart, but no, it’s certainly not the most of anyone.”

Parr has had over 600 exhibitions of his work.

“Every time I do more work, I try and make my CV shorter” because nobody wants to read long CVs anymore, Parr says.

Getting Into Photography

“My grandfather was a very keen amateur photographer who lived in the north of England,” says Parr fondly. “I was brought up in the suburbs of London, and during the summer, I’d go up and visit him, and he was an FRPS [Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society].

“He was a bromoil worker where you bleach out the image on a sort of rough paper, and then you re-ink it in, so it’s like an old version of Photoshop. He was in the bromoil circle and would send around, you know, get a box every month, and then it would be 12 prints. You’d put one in and take another of yours out, and people write comments and criticisms on the back of these prints.

“He lent me a camera. We went out shooting together, processed film, and made prints. So, by the time I was 13 or 14, I had decided to be a photographer.”

The first camera that Parr owned was a Agfa Isolette, a compact horizontal-folding camera for 2¼-inch square pictures on 120 film. The camera was produced in Germany from 1937 to 1960.

Parr, who has influenced generations of photographers, also has his own list of photography legends who have influenced his work and career.

“If I had to pick two photographers who influenced me, they would be Tony Ray Jones and [Gary]Winogrand. If I had to pick six, the other [four] would be Eggleston, William Klein, Robert Frank, and Walker Evans. I mean, these are the great names of post-war American photography.”

Cameras, Lenses, and Films of Choice

In the early 1970s, Parr’s kit of choice was B&W photography with the Leica M2 with 35mm and 50mm lenses.

In the 1980s, Parr used the medium format Plaubel Makina 67 with an 80mm f/2.8 Nikon lens and an on-camera flash, especially when creating The Last Resort (1985). They were “unreliable,” so he went to Mamiya 67 and 66 and used Rolleiflexes.

Next came a Nikon camera with a 60mm micro lens. Parr cannot recall the exact model, as he is less interested in the cameras he uses than the photographs they produce.

In 2017, Parr tried out a different style with considerable use of a wide-angle lens.

In 2018, he captured for The Great British Seaside with a Canon 5D Mark IV, having earlier used previous iterations of the 5D as well.

“I’ve used ring flash,” says Parr. “I used it in Bad Weather, and of course, I got it again much later with the DSLR and the Nikon and used it quite a lot over many years. I still have one when I go out shooting on a bigger project. I’ll take both cameras with me.

“The ring flash, as you know, has a light around the lens, so you get the shadowless studio lighting basically like a portable studio light.”

Parr shot 35mm B&W on Kodak Tri-X. Medium format was shot on Fujifilm Fujicolor 400, a negative 120 film. No chrome or slide films were used. Agfa Ultra 100 ISO was employed for 35mm with the close-up macro lens. Ultra as the name suggested, had ultra-bright colors. He did not use professional negative films but only amateur negative films.

Parr developed his own films in the B&W days, and his last darkroom was in Ireland in one of the bathrooms. When he moved to color, he had them processed by a lab.

“Color negative film and flash gave you very intense colors, and that palette I liked and incorporated into my work,” adds Parr. “It’s very similar to the palette you get in commercial photography.”

Parr also uses a Fuji camera nowadays as the Canon 5D proves to be a little too heavy.

An Ongoing Health Battle

“Two years ago, I was diagnosed with having myeloma, which is a cancer of the fluids of the spine,” he says. “You can never be cured with myeloma, but you can hit a state of remission, so I basically had my stem cells taken out of my blood, and they were stored, then they have a big chemo blast, and then they put the stem cells back in.

“One of the side effects of chemo is your hair grows curly, so I know it’s a very small and rather delightful position where I’ve got curly hair. It’s starting to grow straight now. So, I’m not cutting it for a while. I’m just enjoying the craziness of this curly hair before it goes back to being normal.”

Parr has visited about 70 countries in his lifetime, but his traveling days are now behind him.

“My days of travel are going to be less than now,” he says with a tinge of sadness. “I probably won’t go much beyond Europe. Three weeks ago, I got sepsis when I was shooting in Paris, so I nearly died, but they pumped enough antibiotics into me that I survived.

“I’m going to be a bit cautious about too much travel. When you have myeloma, you’re vulnerable to diseases. It probably was food-based. I mean myeloma, you know they give you ten years if you’re lucky after you’ve been diagnosed, but that’s better than two years.”

Over the following years, Parr will continue with his foundation filling in gaps in his folio of British pictures.

Parr has about 60,000 images in his digital archive. About a third of those have come from film negatives/prints that have been scanned.

Parr is a CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire). The next step up is being knighted (if it ever happens), an honor conferred to Sir Donald McCullin, (born 1935) C.B.E., photojournalist and war photographer, for services to photography in 2016. Parr was awarded the CBE on June 19, 2021, and received the award this month from King’s representative Lord Lieutenant in Bristol.

The Martin Parr Foundation

The Martin Parr Foundation was established in 2015 in Bristol.

“I’ve been collecting photography from my colleagues in the British photography world, and I wanted to start a foundation, so I applied to Register of Charities which I successfully did in 2015,” says Parr proudly.

“In 2017, we opened the building here [in Bristol], and we have an archive, a library, and a gallery. The people who are working for my company, as well as the foundation, are all housed here.

“We aim to collect and showcase achievements in British photography that might have otherwise gone unnoticed. We acquire prints from these photographers, and we have built a fantastic collection over the last ten years.

“I have my own personal archive, which is about three-quarters of a million, and then in the archive room, we have maybe 10,000 prints — five thousand from me, five thousand from other photographers. There are over a hundred photographers and certain ones that we really like so we have a vast collection of Chris Killip and Tom Wood.

“Some [photographers] like Steve Pyke have donated some pictures to us, but generally, we acquire them directly from the photographer by negotiating a price.

“We have a very busy bookshop and a membership scheme, so each year, we must raise £300,000 (~$339,000) from our direct selling and talks and such, and over and above that, you know we have four or five staff that we have to pay. I invested my money towards the foundation to continue acquiring images for the collection.

“It’s (health issues) made me more aware of how precious that time is with family, the people you love, and of course, you know the ability to shoot. You can never take that for granted. This summer, I’ve been very busy and active and appreciated just getting out behind the camera. I often go out with my mobility scooter and shoot events.”

“Photography is the simplest thing in the world,” Parr once said, “but it is incredibly complicated to make it really work.”

You can see more of Martin Parr’s work on his website and Instagram.

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at The International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him here.

Image credits: All photos courtesy Martin Parr.