Interview with Greg Miller

![]()

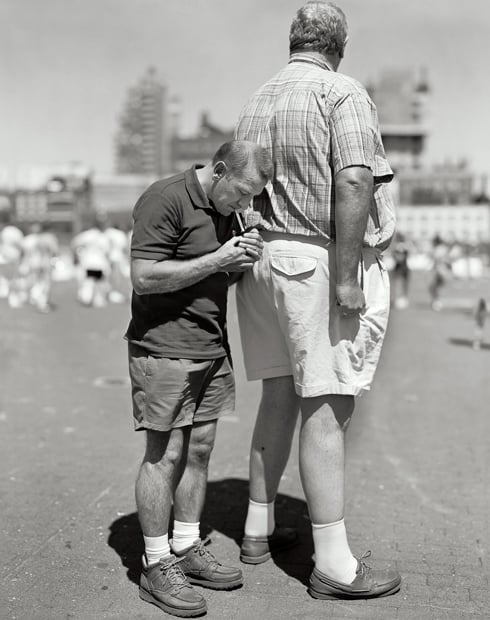

Predominantly using an 8×10 view camera, Greg Miller‘s photography utilizes street photography, found moments and portraiture to capture human relationships and a sense of suspended reality. In 2008, he received a Fellowship in photography from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation. His work has appeared in numerous publications including The New York Times Magazine, New York Magazine, TIME, People, Fortune and LIFE.

Greg Miller: I had the good fortune of starting early. I got into photography taking pictures for my high school yearbook and working for a photographer in Nashville, my hometown. There is a long string of people who influenced me early on but it all really started with my dad who was an amateur photographer.

When I came to New York in 1986 I studied at The School of Visual Arts. One of my first teachers there was Lois Conner who later introduced me to Andrea Modica and Judith Joy Ross. The three of them have been and continue to be really big influences on me. Lois shoots with 7×17 and 8×10 view cameras and Andrea and Judith shoot 8×10.

PP: You’re well-known for shooting your work with an 8×10 view camera. In a world with seemingly limitless technology to work with, why do you choose to work in such an old-fashioned way?

GM: My camera was built in 1998 even though it’s still an 8×10 camera, and it’s film and everything. The reason I love it is really because of the optics and the whole experience with photographing with the large format.

When I’m on the street shooting with this camera, it has this level of importance because it’s a large wooden camera, and I just love the experience everyone has with it, I love everything about it. I understand that it makes me seem like I’m a luddite or something.

PP: What are the challenges and benefits that come with shooting with an 8×10?

GM: I think the biggest challenges are the most obvious ones: it’s expensive and it’s slow and heavy. But given those challenges, the way I work around them actually makes my pictures more interesting. One way is to shoot less.

For example, I used to take a picture to get the person to stop doing what they were doing even though I didn’t like the picture. I don’t do that anymore. I take only the pictures I (think) I want to make. The money part is a drag because it’s almost $1,500 now for a hundred sheets of film. I buy a case at a time and it takes me about 3 months to get through 100 sheets, so when I’m just getting done shooting $1,500 dollars, I have to spend another $1,500 dollars. It’s pretty sobering.

But the camera has taught me how to be more communicative. I talk to everyone in my pictures. I am richer for it in other more profound ways. Makes $1,500 look cheap.

PP: So that process really must force you to be a perfectionist too.

GM: Yeah exactly, you’re really trying to get it in one sheet. But I don’t like to call it perfectionism. I like to think of it as fanatical excellence. I have been working on dropping perfectionism. It’s not good for me.

PP: Do you have any clients who are kind of turned off by the way that you work, just because of the cost?

GM: I’m sure all the people who are not hiring me are turned off by it, haha. The ones who do often embrace it. It takes a certain amount of imagination on the part of the people who hire me. I’m always grateful when they hire me. Ideally, they have an understanding of the process, and they are interested in the magic of it, and not the drawbacks.

I like to think I’m the buffer between the difficulties of the format and the magic. In the end, they are hiring me for how my pictures look not the way they are made.

PP: On the flip side, what are the benefits of shooting with the 8×10?

GM: Well the benefits are huge. The optics are the most obvious thing, but also the way that people respond to the camera. My familiarity and love for the camera makes for a more intimate experience.

PP: Many of your photographs involve close interaction with strangers you meet on the street. Talk about your process about meeting your subjects and directing them for your pictures.

GM: Early on, in 1997, I shot feature photographs for New York Magazine—I’m actually about to put a lot of these pictures on my website, it’s a series called Gotham. These photographs ran small, once a week, in the Gotham section of the magazine. It was during this period that I began going out onto the street with the 8×10 camera and talking to people and directing them.

It was transformative because up to that point I had always photographed people either with a Leica or a small camera without talking to them. I hadn’t realized I was craving to talk to them and was paralyzed with fear. The process of shooting with an 8×10 forced me to overcome my fear of talking to people, and since it was really what I wanted, it changed my life. This summer, a few photographs from this series are included on “The Wall,” an outdoor exhibition in Photoville in Brooklyn Bridge Park.

PP: So how do you decide on who you want to photograph?

GM: I use that same fear as a compass. If I’m looking at 20 people on the street and I can photograph any of them, one of them will make me say to myself, “Oh my God, I can’t photograph that person.” That’s the person I know I should be photographing.

You want to listen to that nerve that goes from your brain to your heart to your stomach to your crotch. You want that nerve to be choosing your subject matter.

PP: You were awarded a Guggenheim fellowship in 2008. Tell us about the process that led up to this award, and what advice do you have for younger generation of photographers who hope to reach this level of success?

GM: The thing about the Guggenheim is that it’s a mid-career grant, so you don’t want to apply for it before the time is right. It has as much to do with your own level as it does with who else happens to apply that year and who the committee is. People have talked to me about it. I met with someone who asked me for advice on how to apply. He kept using the word “winning” or “losing” the grant. It was clear he was thinking a lot about it. I think that’s a not a great way to look at it.

If you’re going to apply for it don’t look at it as winning or losing. Maybe it’s easy for me to say, but I think that it was a lot for me just to apply for it; it changed who I was and how I perceived myself as an artist just in the process of applying or it. You have to approach 4 people to write recommendations for you and also write a proposal and bio. At that point in your career you may not have quite solidified those ideas.

The process of applying can be the award in itself. Of course, that doesn’t come with money. But grant or no grant I believe the money comes if you are truly aligned with the artist you want to be.

PP: You grew up in Nashville, Tennessee, and after establishing yourself in New York, you went back to Nashville to make photographs. Tell us about your decision to make a project about your hometown.

GM: When I got the Guggenheim I wanted to make something really good, and I felt the pressure was on to make something that was really significant. I proposed to photograph marching band camps of the South, and I did actually end up photographing some marching bands, but I ended up deciding to cast a wider net and to photograph my home town. As a starting point, I decided to go back to many of the places that I lived.

My family moved like 17 times in the 18 years I lived in Nashville, we were always moving and it was a little chaotic, so I decided to put pins on a map of the places I had lived and the project unfolded from there. I really tried to figure out how to make this into a body of work.

PP: So was there any specific story you wanted to tell about Nashville?

GM: I wanted to find my childhood. Of course, my childhood is over and done, and my friends and family had moved, my grandmother had passed away. There was nothing left of my childhood. I came back and it was like this modern city in 2008, it could have been Trenton or Minneapolis or any American city, so I wanted to try to find my childhood there. I went back looking for anything in 2008 that would trigger memories of my 70’s and 80’s childhood.

PP: Are there any specific pictures in this project that you feel a special connection with?

GM: Yeah, the pictures of the couple fishing in the river, that’s a place we used to play when I was a kid. Going back to places I played and lived, for me, it was kind of magical when I actually found something there. And also the picture of the minister walking from his car to the church, to me it was like divine intervention when these types of things would happen. When I started this search felt like a stretch, so whenever I found a great picture, it slowly began to feel like it was meant to be.

PP: Another popular series of yours involves photographing people on Ash Wednesday, tell us about this project.

GM: Unto Dust has become a long meditation on the practice of wearing ashes on the forehead by Catholics (and some other denominations) on Ash Wednesday in New York. It occurs on the first day of the liturgical period of Lent. By long I mean that I have photographed it every year in Midtown Manhattan since 1997. This is my longest running project at 15 years (and counting). I have chosen to present them front and center often engaging the camera directly.

I suppose in the beginning, I thought people might be embarrassed to be photographed with their ashes but I quickly realized that this is their religion so people are more defiant and proud than self conscious. It is still a portrait though. I saw year after year that it became repetitive.

Photographically, I had to still make a portrait that I would have liked without ashes. While they are confident, at least enough to get their picture made, you begin to see their vulnerability. That’s why I think it works. While I understand that this is a predominantly Catholic event, my hope is that the message of human frailty is universal. That the faithful and those who struggle to be faithful are one and the same. We are all struggling with the mystery of our mortality.

PP: In addition to being a working photographer, you also teach at the International Center of Photography. What’s the most important lesson you try to teach your students?

GM: I teach a large-format photography class, and it may seem odd in that context but I really like to talk to my students about living life as a photographer on a day-to-day basis.

The ICP program is a 10-month certificate program. It’s great if they figure out how to be photographers in the program but I want them to figure out how to be a photographer after that. If they figure that out, then they have truly gotten their money’s worth. Large format may not be the first thing that comes to mind when you think about making a living in photography in 2013, but I am talking to them in terms of following their bliss.

I have no idea what they will end up shooting or what format. It doesn’t matter. What matters is they have met (as I have met) a photographer that is making his living doing what he wants. Doing what you love is prudent. In other words, doing what you think you are supposed to be doing to make a living is much harder than shooting large format. It will all fall into place if you can just find a way to do it every day. And it isn’t necessarily shooting everyday.

PP: What photographers from the past do you feel you relate to the most?

GM: That’s a good question. I wanted to be Garry Winogrand, and I wanted to be Weegee, you know, and I love O. Winston Link. I might add to that An-My Le, who is not in the past, but I admire her for having the courage to return and photograph Vietnam, her homeland, as an adult. I also can’t emphasize enough Lois, Andrea and Judith who really taught me how to live life as a photographer.

Hanging out with and seeing the everyday challenges that face the photographers you admire: families, parents aging; if you can survive dealing with all that plus, you know, make enough money to pay $1500 for film, you’ve got the whole game right there. You just don’t see that stuff when you see pictures at an exhibit or in a book.

PP: In terms of the way that your pictures look, your own personal vision, what other photographer have inspired you the most or you try to emulate or have a similar vision?

GM: I teach in the Photojournalism and Documentary Dept. at International Center of Photography and I’m influenced by a lot of photojournalists. I have a lot of respect for their world. I’m not a photojournalist, but I hold the people who live that life in very high regard.

It’s sad that Tim Hetherington died so early because he was such a great photographer, and for him to be in that war zone trying to do something completely different was so good. When I look at his pictures all I can think about is what a huge tragedy it is that he is gone.

Also, I love Nina Berman’s photography. I think she is very brave in her work. I think that’s what it’s all about.

PP: I’ve always read your pictures as romantic and idealistic, not really any elements of drama, they strike me as a type positive pictures do you have any thoughts on how your own personality come through your work.

GM: There’s that scene in Down by Law where Roberto Benigni meets Tom Waits and he says: “It’s a sad and beautiful world,” and Benigni writes that down in his book of English phrases and repeats it throughout the film. That’s kind of the way I see the world and that’s the kind of the picture I make.

I don’t like cynical photography, but that’s because it’s not the way I see the world. I see it as funny and beautiful and I think it is sad, it’s all those things at once. If I can make a funny picture all the time I would. Humor in photography is such a blessing, it just doesn’t happen that often.

PP: What projects are you currently working on?

GM: I just started a new project photographing in my town, Mansfield Center in Connecticut. I’m photographing kids waiting for the school bus.

PP: Is that a kind of reaction to the Newtown shooting that occurred not long ago?

GM: It is, yeah. I was really rocked by the shooting and I was looking for a way to release some of that in my photography. I could go to Newtown to photograph, but it just seems exploitive to go down there. I had this idea two years before, but it was that event that really got this project started.

PP: It seems like an interesting spot to be in because you make pictures in this beautiful and heartwarming way, but you’re alluding to this very dark event that occurred, do you think it will change the way you make this project?

GM: My pictures ride that line between dark and joyful. I think this project is about how vulnerable we all are. Whenever I look at the news—and I try not to, but when I do—it seems to be stories beyond my comprehension, beyond my ability to accept.

I wanted to photograph Sandy Hook but it was impossible. People magazine hired me to go down the weekend immediately after, but the pictures were terrible and it was miserable making them. All I wanted was to leave that town alone.

Every photographer in a way was missing the moment. In fact, for the first time in my career, I wanted to not get back to the moment but go back to before the moment and make sure the moment never happened in the first place. The next week People magazine, the Daily News and other news outlets ran grids of victims’ faces on their covers. My hope in photographing the kids waiting for the bus is to appreciate and celebrate the children before they are a headline.

PP: What is the key for a successful career in photography, what are the most important characteristics in succeeding in this field.

GM: If I was going to bless someone, I would bless them with time. I feel the young photographers I meet don’t feel like they have any time to make pictures and to walk around and see the world. They feel pressure to come up with a project that will be the next big thing.

I don’t think we’re emphasizing enough what it’s like to be an artist and what it’s like to figure out how to survive financially, to allow the time for the work. It’s about finding the time and making money to support yourself. I think people feel rushed; talking to my students I try to slow them down and get them to look at the world. It’s also important to be good to yourself, to accept yourself. That alone can do wonders for your life. I think people are really hard on themselves.

PP: Can you describe some of your own early struggles when you were trying to make a name for yourself?

GM: Looking back at it I’ve always felt I’ve had some lucky strokes. I’ve always worked hard and they say there’s really no luck in the world; there’s only hard work. I think that, for me, I remember being particularly lonely, and there were days, weeks, years of nobody giving a s**t about my work or about me, and that is particularly hard.

I think the hardest days were the 2-5 years right after school, and there were good times and everything but I didn’t feel like I knew who I was or where I was going or anything like that. In retrospect I had an incredible amount of freedom in that time, if you can have that type of freedom without loneliness, that’s kind of brilliant, but there’s a part about growing up that’s not particularly comfortable.

PP: What are you looking forward to over the next year, photographically or otherwise?

GM: I’m actively working on the dummy for my book about Ash Wednesday called Unto Dust. I’m looking for a publisher, or I might self-publish.

PP: Any else you’d like to say? New developments in your life?

GM: We’ve just moved into a new house in CT, and my wife is due for our second child in July. That’s pretty big.

PP: Are you excited? Nervous?

GM: I’m excited about it, it’s a beautiful thing. I love to sleep so I’m a little sad about losing sleep but it’s uncharted territory, having two kids and a new house. These days I feel like I have a lot of people that I am there for. I am there for my wife and children, my parents, my wife’s parents. Expand that circle and I am there also for my students and the people who hire me.

You know, you grow up and you actually become someone that people can count on being there. It’s scary, yes, but mostly in the area of children. You really want to be there in the way that they need you to be. I used to be concerned about whether people thought I was a good photographer or not. Nowadays I am more concerned with being a good husband and a good dad. Luckily, I don’t think that has made me any less of a photographer.