Why is Shooting with a Smartphone So Deeply Unsatisfying?

![]()

The smartphone is perhaps the single most important device in history, wresting the power of news and journalism back into the hands of the everyday person. Data communication is the key enabler, but the camera — more than anything else — slakes the thirst for instant visual gratification. So, why is shooting with a smartphone so deeply unsatisfying?

The 2000s have therefore been epitomized by personalized mass media where everyone has a voice and the smartphone is one of the key components in this stratospheric shift in how we communicate.

All Hail the Smartphone

The shift to the smartphone is in part because of the data connection that allows instant communication, but it is more than that. In the past, if a media outlet wanted to cover a news event, it may have had to send a journalist, photographer, and film crew with the requisite costs for staff, equipment, and travel. The smartphone combines all of these elements placing them in the hands of an on-site individual, albeit potentially one without the skills of a professional.

It’s, of course, one of the reasons for the broader demise of print media and journalism, but the boon is clear: coverage is near-universal and cheap.

![]()

Consider those aspects for a moment. For something that’s barely the size of a purse, you can photograph, video, edit your media, write copy, and publish, all from a device that costs as little as ~$100. That’s an incredible achievement where features are constantly evolving: 4K, slow motion, night shooting, and phone tracking to name but a few.

The citizen journalist doesn’t need anything else other than the phone in their pocket and to be in the right place at the right time. The difference is that there is no longer one Cartier-Bresson or McCullin, but an army of them. There will always be someone in the right place at the right time.

Down with the Smartphone

Given the remarkable accolades that I’ve been laying at the door of the smartphone, why does it leave me cold when I come to shoot with it? In fact, why does it fill me with dread? I think there are three reasons.

Reason #1: Physics

Let’s dispense with the technical element first. Whichever way you look at it, the cameras are poor. In fact, very poor.

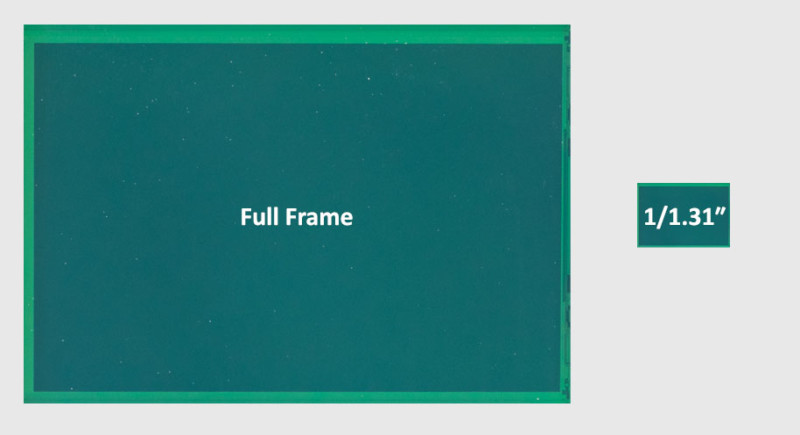

Take Google’s latest offering, the Pixel 6. The primary rear sensor is a 50-megapixel (downsampled to 12.5-megapixel), 1/1.31″ unit with 1.2 µm pixels and a 24 mm, f/14, equivalent lens. That has won plaudits from reviewers as the sensor is nearly twice the size of the Pixel 5. Compare that to Nikon’s D850 from 2017; this has a 46-megapixel, full-frame sensor with 4.35 µm pixels and a lens… well, take your pick.

You can happily take raw files from a Pixel and process them using Snapseed, but don’t bother as the output won’t be worth looking at. Those small pixels produce rudimentary files and the magic in a smartphone happens in the post-production, combining multiple images and resampling from that 50-megapixel camera to smooth the noise out, pump up the saturation, and sharpen the detail.

Google does a remarkable job… if you want to publish on social media. But under the forensic inspection of a professional photographer, it won’t stand up. However it’s not just the pixel size under scrutiny, but the equivalent lens as well. While you can make use of a 24mm-equivalent field-of-view, it’s the f/14 equivalent aperture that is the killer and the obvious reason why “portrait mode” with simulated bokeh has become a focus for developers.

There’s no cheating the physics of a large sensor and the big glass to match it. In short, you are drastically limited in options and then reliant on the post-production magic to hide the technical failures. There’s a reason why, in the early 2000s, consumer compact cameras produced such awful images; yes, the sensors were relatively old designs, but more than that, they were small. The instant gratification digital party trick soon wore off and you will still find many an old camera languishing at the bottom of a cluttered tech drawer.

These cameras were simple devices and the images they produced were straight-out-of-camera (SOOC), with a little JPEG post-production on-the-fly. That took an appalling image and rendered it slightly less bad. In comparison, early smartphone images were of the same order, but current post-production techniques now ingest poor images and make them look genuinely good, at least when you are viewing them on social media.

The reason for the small sensor was to produce a small camera that was integrated into the phone. Post-production has been a largely successful attempt at mitigating the impact on image quality. We now select a camera mode and let the algorithm produce the desired result, alongside any filters we may choose to add. The smartphone has become the de facto jack-of-all-trades and it really is the master of none.

Reason #2: Ergonomics

The second reason for dreading shooting with a smartphone is the ergonomic element. Smartphones are essentially a screen for interacting with a computer… a flat slab. It is not designed to be held up securely and I then have to use a finger to stab at the shutter button; about as unergonomic as you could get. When was the last time you saw a handgrip on a smartphone?

I contrast that to my well-used Nikon D800; I can press the shutter butter while holding the camera which is secured with a wrist or shoulder strap. My fingers easily curl around the molded grip and it genuinely feels like an extension of my eye.

![]()

Reason #3: Fascination

The final reason is an emotional one and perhaps this won’t affect the vast majority of smartphone shooters. However, I love having a dedicated device, understanding the constraints on my image-making, and then creating the best images I can. Perhaps that is the fascination of photography, combining the creative and technical components, a fusion of art and science. The little black box that is the smartphone is a dumb device.

The Future of the Camera

The camera as a mainstream consumer device is dead. The implosion of sales since 2011 is well documented; the industry is fast returning to its niche status and it would be interesting to know how many households actually own a stand-alone camera. There is no value proposition for the casual user, which is why manufacturers now focus on the hobbyist and professional markets.

Of more concern to manufacturers is whether smartphone post-production will make genuinely great images and one big step on that journey is the use of computational raw, such as Apple’s ProRAW. The smartphone will always be constrained by size, whereas the dedicated camera isn’t, but we are already seeing a convergence of design ideas and perhaps the Zeiss ZX1 is an early exemplar of where the industry might go, at least in part.

The physical designs, while needing refinement, are less of a problem than the software implementation. Computational photography has been implemented in fits-and-starts by manufacturers and remains niche; until they can take the large step and genuinely implement an open computational platform, the sector will be held back.

That doesn’t stop shooting with a smartphone from leaving me cold. I want the enjoyment of framing, of making a creative choice when selecting aperture and shutter speed, of wandering – camera in hand – feeling like Cartier-Bresson hunting for that single evocative frame. The problem is, I want a device that doesn’t exist at the moment and I’m frustrated that neither smartphone nor camera manufacturers are making it.

Until the day my dream device lands, however, I’ll keep on shooting with my smartphone.

Image credits: Stock photos from Depositphotos