Why I Lit Up Lytro and Scrapped the Strategy as CEO

![]()

My name is Jason Rosenthal, and I’m the CEO of Lytro. A little over a year ago, it became clear to me that we needed to drastically change the direction of our company.

Were consumer cameras really our biggest and best opportunity? If not, what should we be focused on instead? Could we pivot dramatically with so much invested in our current direction?

![]()

I’d joined Lytro in early 2013 with the conviction that Light Field technology had the potential to be even more transformative to imaging than the transition from film to digital 15 years earlier. Lytro initially gained attention for the ability to refocus pictures after the fact but the implications of Light Field technology run far deeper.

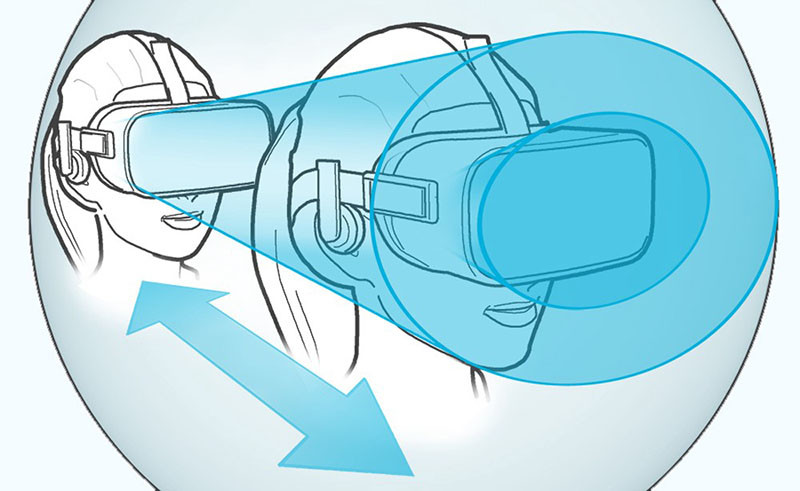

While traditional photography captures the brightness and color of light, a Light Field in addition captures the angle and direction of every ray of light, essentially creating a 3D model of the entire scene. This additional data unlocks a host of previously impossible capabilities ranging from the ability to create photo realistic immersive 3D worlds, to new ways of integrating computer graphics with live action, to ultimately software eating cameras as we know them. Lytro was founded by the incredible Dr. Ren Ng, now our Chairman and a professor at UC Berkeley, and was based on the pioneering work he did at Stanford for his PhD.

The incredibly hard part, as it turned out, was figuring out which application and market to apply our technology to first.

As my doubts about our product direction grew, we started to hear from a growing chorus of Virtual Reality companies and Hollywood studios that they were looking for a Light Field powered solution to help them realize their creative vision for cinematic VR and next generation content. The more I looked at the needs of this market, the more convinced I became that we had something unique to offer.

We had just raised $50MM in new capital. We didn’t have the resources to both continue building consumer products and invest in VR, so I knew I was going to have to pick. This realization made me sick to my stomach since we had built an entire team and company focused on the consumer business.

![]()

If you believe what you read in the tech press, the streets are going to be stained with Unicorn blood; but from my perspective we’ve seen this all before. For anyone who chooses to spend their career building technology startups, we will see it all again. In my experience, building a technology startup has always been hard.

There have been many nights when I’ve laid awake just wishing sleep would come or trying to solve and resolve the day’s crop of problems for the thousandth time. On the good days, building a company feels lonely, scary and confusing. On the bad days, I’ve wanted to vomit and curl up into the fetal position rather than deal with my reality.

I was one of the first five employees at Loudcloud and over my eight years we experienced both meteoric success and a seemingly relentless string of challenges that tested all our resourcefulness and creativity from the leadership rung on down. We grew the initial team of five in September of 1999 to over 500 employees by the end of 2000. During our first year, we had such overwhelming demand from customers for what was essentially a precursor to today’s Amazon Web Services that we invented the notion of “Customer Slots,” which were basically upfront deposits for services that might not be up and running for another six months. I was in charge of customer deployments and one of the hardest parts of the job (I naively thought) was juggling these slots.

We signed huge customers like Nike, Encyclopedia Brittanica, Fox News and Fox Sports and many others. Our board told us repeatedly that we should plan our business assuming cash was free because at the time it basically was.

Then, things started to get tough. First, the dot com crash effectively closed the capital markets. We were the last tech company of that era to go public in March of 2001. Shortly after our IPO, we laid off 33% of our company. Mass bankruptcies of many of our startup customers followed which left us holding the bag on expensive long-term server and data center leases. We were burning $40MM of cash per quarter with no way to put additional capital into the company. Then 9/11 happened, which only accelerated the downward spiral of the whole market. Another round of layoffs followed. Through a small miracle, we were on the verge of being able to raise some additional capital through a vehicle known as a PIPE (Private Investment in Public Equity). A few days before we were supposed to close, our largest customer went bankrupt itself. This was a material event for the company which in turn killed our PIPE. A third round of layoffs followed.

We began to hear regularly from prospective customers that they weren’t interested in our cloud services. In their minds we were on a certain path to bankruptcy. But it wasn’t all bad news: they were very interested in buying the software we had developed to automate the operations of our own data centers, called Opsware. It took us a while before the penny dropped, but we finally understood. We needed to stop selling cloud services and sell Opsware technology to large enterprises instead. This realization and pivot was only possible thanks the incredible foresight of our CEO, Ben Horowitz, and the deal making skills of our head of business development, John O’Farrell, who together sold our cloud business to EDS for $65MM and simultaneously signed EDS up as our first and largest customer for Opsware.

Over the course of the next five years we built Opsware into a successful enterprise software business that we sold to HP for $1.6 billion in 2007. The transaction closed in September of that year, about 20 days before the start of the financial crisis but that’s a different story. All of this is beautifully chronicled in Ben Horowitz’ must read book for CEOs, The Hard Thing About Hard Things.

As I pondered the best course for Lytro, memories of the Loudcloud experience and the dotcom bust loomed fresh in my mind.

We’re often told that in challenging times, the best course of action is to put your head down and power through. However, I’ve found that sometimes the most courageous thing to do is realize that the path you’re on simply won’t work no matter how hard you push yourself and your team. In those situations, often the best approach is to find a better path.

When I took over as CEO of Ning in March 2010, we had over 350,000 active social networks on the platform and over 60,000,000 monthly uniques. The idea was to make it super simple for anyone to create their own custom social network and to build an advertising based business around our users and page views much as MySpace and Facebook were doing. Unfortunately, in 2009 growth stalled and try as we might, we couldn’t figure out a way to reignite it. Additionally, many of our social network creators hated the idea of bringing ads to their sites. The company was burning almost $4.5MM of cash per month and things were getting scary.

After a lot of analysis of our traffic, usage and potential options, we came up with a crazy idea. There were a tiny number of social networks, less than 1% of the total active sites on the platform, that were paying us a small monthly service fee of roughly $20/month. It turned out that despite their small number, these sites were generating a disproportionate share of traffic, usage and engagement so clearly there was something working here. After looking at all other options, we decided to flip the entire Ning platform from a free ad supported model to a premium subscription service. This meant that every social network creator would have a limited period of time to decide if they wanted to keep using Ning for a small monthly fee or move to a different platform. We offered multiple pricing options ranging from less than $3/month to $49/month depending on what set of features they wanted. We also provided tools so that Ning Network Creators could export their data and move to a different platform if they so chose.

This was not an easy or clear decision at the time. In early 2010, the idea of getting people to pay a small monthly fee for an online service was not nearly as widely accepted as it is today. However, it seemed like the best of a bad set of options. Making this transition required us to rebuild major parts of the product and included laying off 40% of our company to conserve our dwindling cash. When we announced this plan in April 2010, I received my fair share of hate mail much of which read like this gem from one of our religiously themed social networks:

“F**k you and f**k your whole company. You are personally going to burn in hell and have no one to blame but yourself.”

In the time between the announcement of our strategic shift and the actual implementation, I sometimes woke up at night in a cold sweat thinking that perhaps nobody would go from free to paid in which case we would have no choice other than to shutdown the whole company or try to orchestrate some form of acquihire scenario. We had an informal pool going on within the company around the percentage of free social networks on the platform that would convert to paying subscribers. Our guesses ranged on conversion rate ranged from 0.1% to 1.5%. To be provocative, our VP of Engineering bet that we could get as high as 7%.

As it turned out, all of us dramatically underestimated our conversion rate. Our actual conversion rate was almost 10% and we went from less than 3,500 paying subscribers to almost 35,000 within a span of weeks. Within the first year, we had grown that number to 100,000 and were generating over $1MM per month in revenue up from tens of thousands of dollars prior to the shift. Even more powerful was the fact that we could focus all of our product and development effort on the needs of our subscribers vs. having to concern ourselves with vanity metrics like users and page views. With changes like this and many others we saw customer satisfaction soar along with revenue. In order to successfully make this transition we needed to divorce ourselves mentally and physically from a whole set of features, code, metrics and infrastructure that in the old world we held as sacred. Letting go of these things felt crazy and painful but it was the only way to make the transition.

Many of these learnings and experiences resonated as I thought about the right next step at Lytro in late January 2015. I realized that we simply were not on a path to build a winning product.

While consumer Light Field cameras offered a number of true technological breakthroughs such as interactive 3D pictures, radical lens specs, and the ability to focus a picture after the fact we had a number of disadvantages as well including 4X larger file sizes and lower resolution in comparison to other similarly priced cameras. The cold hard fact was that we were competing in an established industry where the product requirements had been firmly cemented in the minds of consumers by much larger more established companies. This issue was compounded by the fact that the consumer camera market was declining by almost 35% per year driven by the surge in smartphone photography and changing consumer tastes.

To make matters worse, continuing down the path to build our third and fourth generation products would have consumed more than half of the new capital we had just worked so hard to raise. A financial bet of this size was almost guaranteed to end the company if we got it wrong.

We had a regularly scheduled board meeting on January 29th, 2015 and I knew I needed to make a decision and recommendation about our direction. Weighing heavily on my mind were the impact to our team and the fact that we had recently raised capital with a plan based on our consumer strategy. I was about to present a dramatically different perspective. In the meeting, I laid out the range of options to our board including my recommendation that we dramatically cut staff to reduce costs, exit the consumer business and change direction. The silence that followed my presentation felt like it lasted days. Our newest investor, Mark Flynn from GSV Capital, was the first to speak: “we invested in Lytro because we were excited about the potential of Light Field technology and believed in the team, not because we wanted to be in the consumer electronics business. If you think you have a better path, go make it happen.”

Over the course of the next several months, we worked to wind down our manufacturing operations and supply chain in Asia and sell through our remaining inventory of consumer cameras. The bulk of the team began experimenting with different approaches to real world Virtual Reality which culminated with our announcement of Lytro Immerge in November. We’re still in the early days with Lytro Immerge but the product-market-fit of Light Field technology and VR has exceeded even our highest expectations.

As with building any new product or company, we will have many interesting challenges to solve and I know there will be curve balls ahead. However, my middle of the night panic attacks are gone. I wake with a burning desire to go to work because I am so excited by what we are building and its potential to help shape VR. I’m surrounded by an amazing team. Hardly a day passes without one of them stopping me in the hallway and uttering my five favorite words: “Want to see something cool?”

About the author: Jason Rosenthal is the CEO of Lytro. This article was also published here.