The True Photographic History of ‘The Rule of Thirds’ (and Golden Mean)

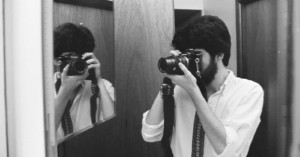

This is a photograph that was on the wall of my house when I was growing up — it’s Jerry Uelsmann’s Self-Portrait as Robinson & Rejlander (1964). I always wondered who those guys were. I was about to find out.