My Unnatural Interest in Cracks

![]()

I can’t remember the first crack I photographed. But I remember the huge crack in the plaster on the outside of my apartment building in San Rafael after college.

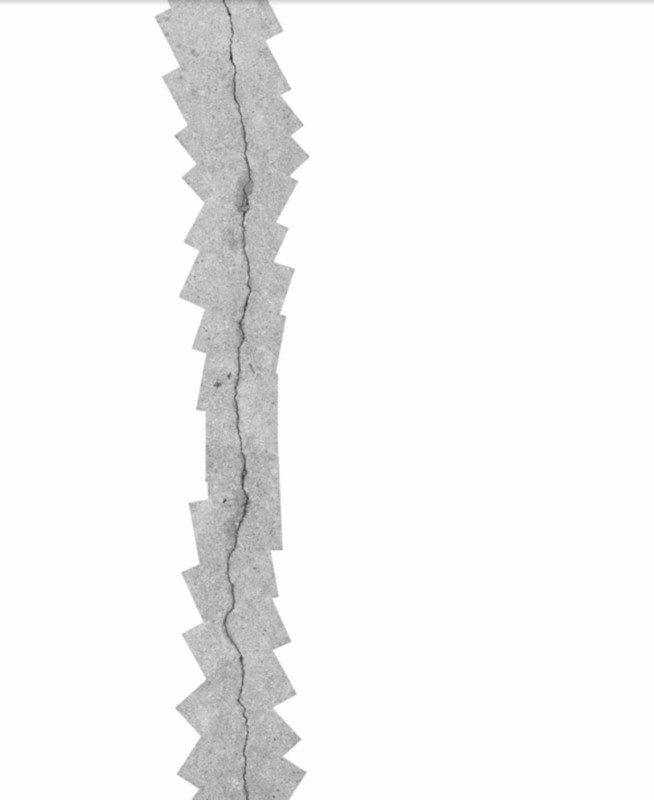

I had been particularly inspired by a planetary geology course, and I had the idea to photograph the crack in the same way that satellites over the moon photographed the lunar surface, and make a mosaic of it. This became something I did.

For years I made mosaics of cracks — enormous compositions sometimes, and I played with the camera orientation, causing the mosaic sequence to loop and rotate as it followed along. This was great when you could go to a Photomat and get a stack of prints from your roll of film.

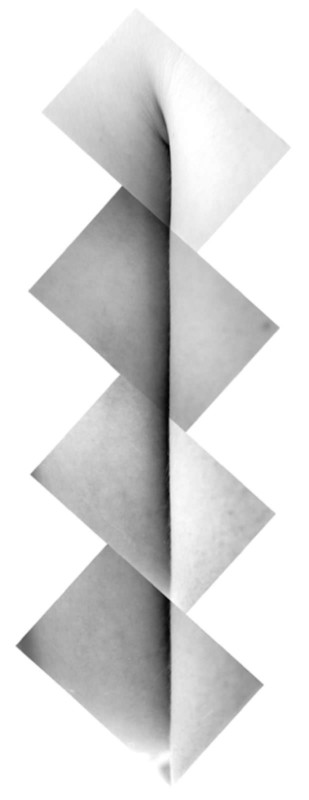

I followed junctures and seams too, and even the sexy lines on the human body, but this went down a rabbit hole of focusing on the orientation of the frames. This was fun, but they never were more fun than the cracks.

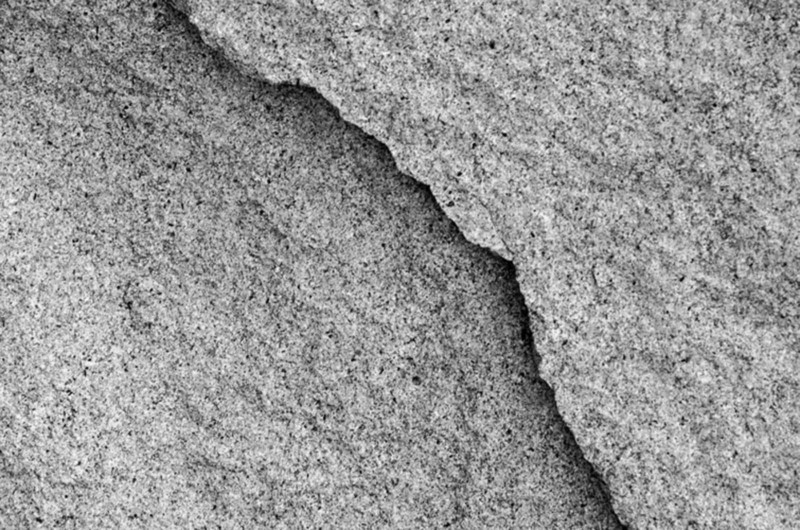

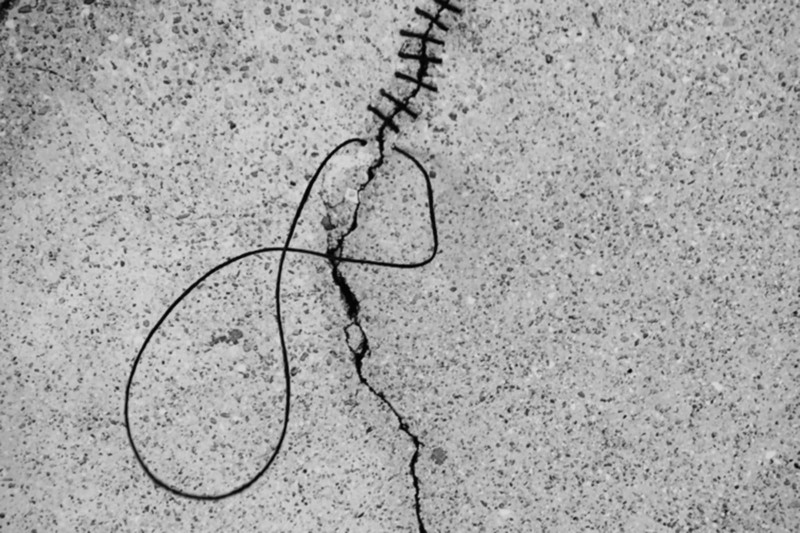

A good crack is an enormously satisfying thing, like a lightning bolt or a branch of an old oak tree. It has something to do with fractals, the mathematics of randomness, and something that had interested me since college days and they first came to light in the 1980s. Over the subsequent decades, I photographed thousands of cracks — in stone, concrete, plaster — with an eye on that fractal nature. It’s hard to describe what made a crack great.

Here are a few memorable ones:

You get the idea. I had a bunch. It embarrassed my kids when they were out with me and I had my camera. I’d see one and have to stop, and my 14-year-old daughter would step away so as not to be seen with me. Passersby would stop and ask me what I was looking at on the ground. “Dad, please! Let’s go!”

She threatened to get me a t-shirt that said “Don’t Call The Police, I’m a Professional.”

I’ve thought a lot about cracks. Cracks are gentle reminders of our impermanence, of the steady drumbeat of entropy. We cling to the Earth as if it were static, and act surprised when it is not. We all break under the alchemy of time, the pressures of life. Cracks are snowflakes, unique fingerprints of our modernization, and each tells a story if we only stop moving and look down. They’re so ubiquitous they’re invisible. But not to me. They’re part of my photographic mantra to slow down and pay attention.

A friend gave me a little book on wabi-sabi in 1994, which deeply affected me. It perfectly articulated the joy in all these imperfections. But it wasn’t until 2015 I first learned about kintsugi, the Zen art of repairing broken ceramics with gold. I liked how the artform cherished flaws, highlighting the cracks, and transforming the mundane into the precious. This felt like an important human lesson.

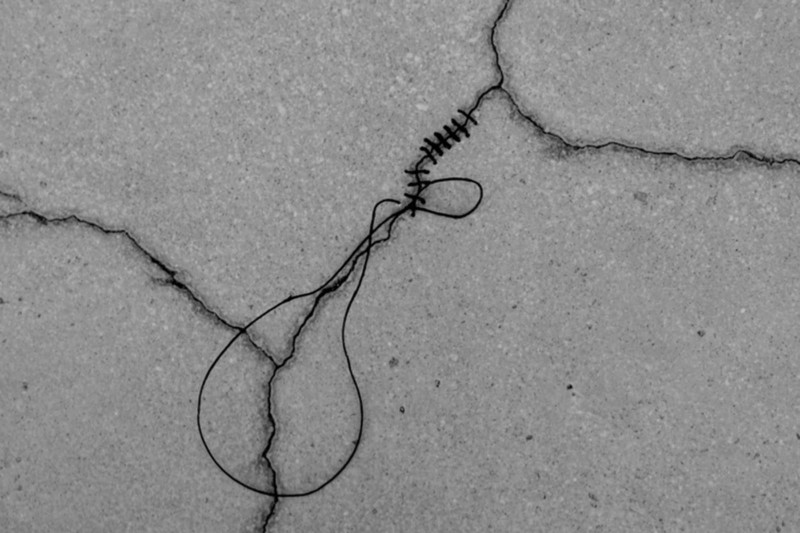

But my crack exploration was reborn that year when I made the connection between these beautiful fractals, the Zen aesthetics, and the Jewish concept of tikkun olam — literally translated: “to heal the world.” Tikkun olam reminded me that the world is broken in myriad ways and it is my obligation to fix it.

So I made very large prints of cracks I liked, and I got a needle and thread and began to suture them up. This was my work to heal. They looked a little bit like my head after my brain surgery. I wasn’t that into how they looked when done, but I really enjoyed sewing them. In particular, while I sat in my living room and pushed the needle through the photographic paper, I loved the way the thread twisted, and the shadows cast on the paper while I worked. So I grabbed my camera, thinking I’d document the process.

While suturing up the cracks is tikkun olam, it is also kintsugi. The world, even broken, is precious and worthy of reverence, maybe more-so. We heal the world not because the cracks are bad, they are the very essence of humanity; we heal the world because it is our job.

What I discovered was that the process of sewing them was more interesting than having them sewn. And the images of me working seemed more enigmatic than anything I could have imagined, almost “Uelsmann-y” surreal. And that became my project — not to create a mixed-media object, but to make a photograph to document my sewing up of cracks. Tikkun olam isn’t the healed world, but our work to fix it. This is my response.

More of my photographic explorations are on my website and on Instagram.

About the author: Michael Rubin, formerly of Lucasfilm, Netflix and Adobe, is a photographer and host of the podcast “Everyday Photography, Every Day.” The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. To see more from Rubin, visit Neomodern or give him a follow on Instagram. This article was also published here.