Synecdoche: The Essence of Photography

![]()

I was struggling through Caesar in 10th grade Latin class when I first heard the term “synecdoche” (although the term is from the Greek) — it’s a figure of speech where a part of something is used to represent the whole. Today, familiar synecdoche include “threads” to mean clothing, as in “dig these new threads I’m wearing.” Or “boots on the ground” when talking about soldiers. Or “she got a cool set of wheels” to mean a new car.

Around that same time, I was falling deeply into photography, and it always seemed to me that a photograph was a synecdoche too. And understanding that rhetorical device helped me evolve in the way I captured subjects in photos. So while a synecdoche is certainly a literary form, I’ve always felt its application was broader.

Visual Synecdoche

The world is all around us, in 360 degrees, all the time, rich in visual data, and a photograph is a tiny little rectangle we use to clip out a small bit of visual space. We don’t show everything, we show this frame. And we expect that small frame to represent more than just that slice.

But even more than that, the way the photo slices up visual space to represent things can be somewhat poetic. When we shift from “obvious” to “obscure” sometimes we’re moving from a headshot to something oblique.

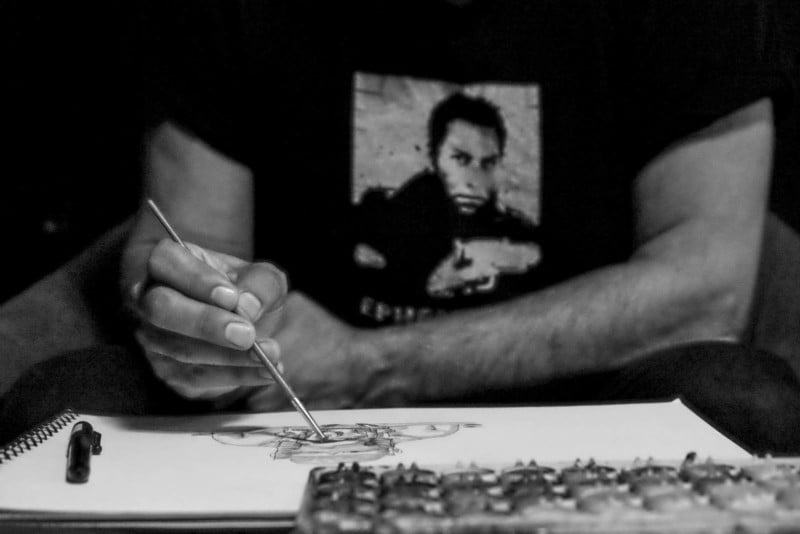

Here’s a photo of Adam Savage holding his amazing replica of the Maltese Falcon. It’s a decent iPhone snapshot, a standard kind of documenting portrait. But to create a more interesting portrait of him I didn’t need his face shot, fully lit, clearly representing everything going on — that could feel like too much, too typical, too obvious; I could take a photo of his hands, just a bit of the statue peeking out. That’s a synecdoche. Or a profile. Or a shadow. It doesn’t have to be a big complete document, it can be just a part, and I use that to represent the whole.

It wasn’t a huge cognitive leap, of course. I was familiar with classic photos like Alma Lavenson’s self-portrait (just her hands around her camera), and even Kertesz’s portrait of Piet Mondrian, just his pipe and glasses (which I might argue is more metonymy*, but we’re splitting hairs.)

Here are other of my portraits that are more poetic as visual synecdoche.

Photos can represent our intended subjects directly, but they can also be synecdoche, and represent them more obliquely.

Temporal Synecdoche

Photos also slice a teeny fraction of a second from the infinite continuum that is time. I take this 125th of a second and save it, and use it to represent all these seconds, all these moments — of the party, of the vacation, of my afternoon. This is also a kind of synecdoche — a split second representing an event.

It works on a larger scale too. I’m on vacation, and I don’t need to photograph everything I see, every day of the vacation. I’m not a journalist covering the event. This isn’t my job. I’m in my life. I don’t have to live behind the camera and experience everything through that filter. My photos sample the time I’m away.

I could take a few photos one day, and they could represent the entire vacation — a few fractions of a second and they signify two weeks in Paris. When you want to see my photos from the trip, I don’t show you all 3000 shots I took; I cull that set down to 20… or 3… and these get posted to Instagram or pasted in a scrapbook. They represent.

This is how photos become iconic. Think of all the great news photos that may have started as a snapshot of something — like the flag being raised on Iwo Jima by Joe Rosenthal — the image of that moment has come to represent something quintessentially patriotic, a kind of synecdoche.

I used to believe that the editing process involved searching for the quintessential photo shot of something, the iconic photo. I’ve come to believe that any number of shots might be a good representation of a person or event, and the fact is that the selection process is what makes one image iconic. Like being on the cover of Life magazine or being shown in a museum. There are many right answers, but you pick one, and that spotlight raises a photo to a new level.

Synecdoche is the essence of photography; image-makers are constantly selecting bits of space and time to describe their experiences. It’s the defining attribute of the art form. And once you fully grasp this concept, it liberates your picture-taking to be more inventive and poetic. Try it.

*Metonymy is similar, but it’s not a part of the thing representing the whole thing, but some other associated object — like saying “The Crown” to mean the queen. In photography, this would mean the portrait didn’t really have any of the person in it, but just their stuff. We do this all the time in visual storytelling — it’s a cut-away shot that adds texture and flavor.

P.S. If you enjoy this way of approaching photography I encourage you to take one of my workshops through the Santa Fe Photographic Workshops. There are periodic 3-week online programs (6 sessions), and this summer there is an in-person 1-week intensive that should be fun for any creative amateur, maybe if you’ve plateaued, feel like you’re good at picture taking, but want to push yourself. Anyway, Thanks for listening.

About the author: Michael Rubin, formerly of Lucasfilm, Netflix and Adobe, is a photographer and host of the podcast “Everyday Photography, Every Day.” The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. To see more from Rubin, visit Neomodern or give him a follow on Instagram. This article was also published here.

Image credits: Header photo from Depositphotos. All other images copyright © 2021 MH Rubin.