Seeing Versus Shooting as a Photographer

![]()

The photographer Dorothea Lange once famously said “A camera is a device that teaches you to see without a camera.” I always loved this quotation. Once you get good at shooting, you start to see the world like a photographer — you notice things, you notice light, you look slower, you take pictures in your mind. The camera saves them, but even without one, you see differently.

Stopping Time

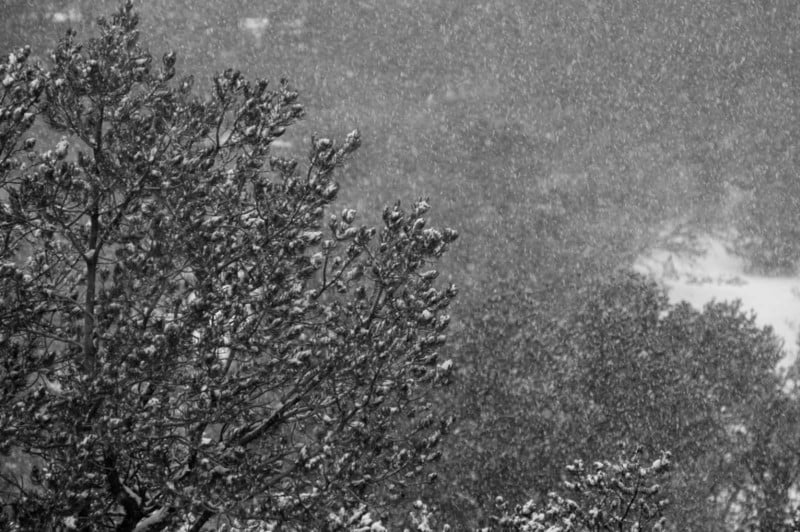

You look out at a breathtaking vista, sunlight scintillating on the lake or autumn leaves flitting in the breeze — and you take a picture… and upon examination, the photo just feels flat. Your eye is processing the delightful motion in a billion sparkles, but in freezing that motion, you see it’s not the sparkles but the changing sparkles that are so delightful. This can be difficult to capture. I find this equally true with the magic in a snowfall or rainstorm — it’s very tricky to capture the scene the way you experienced it because the magic is in the motion and depth.

Once you recognize that a still photo will never recreate motion the way you saw it, you have a few creative options. The first is to slow down the shutter speed. You can get closer to the experience by allowing those moving objects to change while the picture is being taken. It will produce some blur or streaks and that is one way to feel the motion. It takes experimentation in the moment to determine how long a shutter speed to use, which of course depends on how fast the objects are moving and how far away you are from them, and ultimately, how steady you can be for how long. Snow is slower than rain.

Of course, it’s always a game in photography — how long do you leave a shutter open — how much of a slice of time do you want to encapsulate? because as time increases the slice becomes a volume of time that you’re flattening. Michael Kenna’s gorgeous scenes are quiet and devoid of humanity in part because his shutter speed is slow, and thus the volume of time in the photo might be hours, freezing only those things that are unchanging.

Beginners in photography explore freezing a live-moving 3D scene into a 2D slice, but where time is a variable. That’s novel and weird. And fun.

At the other end of the spectrum, you stop time and the image looks very different from how our mind experiences a moving moment. A stopped raindrop is actually hard to see. So when something catches your eye, you also have to recognize what it is about this scene that makes you want to save it—because it’s often something about motion and time, and these are more difficult to save than light.

Brain Ignoring Details

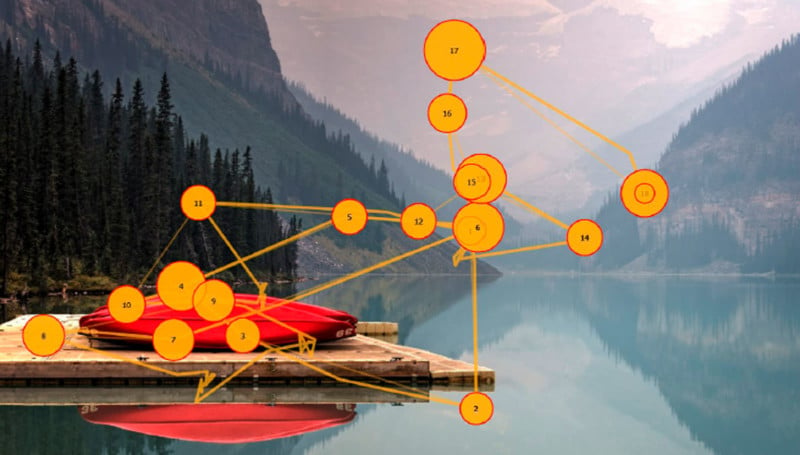

There’s something wonderful about the human visual system, and how it scans a scene — called a saccade — stopping momentarily at one fixed point, then zipping to another, and sewing bits together into a seamless whole with imperfect and changing information.

The content that is not specifically picked up in this saccade is filled in by our brains — what fits with the rest of the fuzzy peripheral data we have, sometimes what we expect to see there.

This is made obvious when you take a picture — you might imagine it’s just a picture of that cool tree, but your brain is ignoring lots of cluttering objects in the distance and foreground. The camera, on the other hand, doesn’t ignore anything. What began in your head as an elegant image of a beautiful tree becomes a cluttered snapshot where the tree is hardly magical. It’s an optical illusion.

The practice is training yourself to notice things inside your camera frame, and coming to understand how they’ll look when shot with different settings.

Left vs Right Brain Seeing

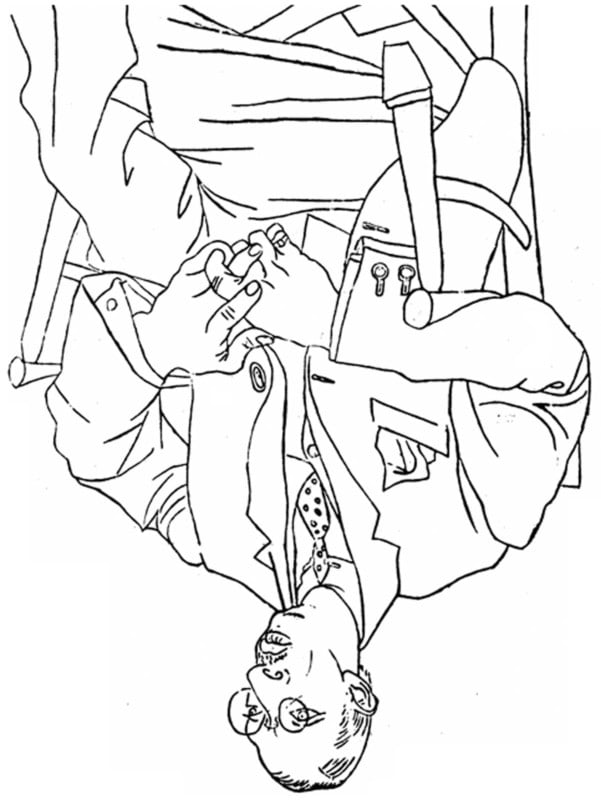

In her book Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, artist Betty Edwards asks students to copy a line drawing of a guy in a chair. The drawings are horrible. Then she has them turn the drawing upside down and do it again. This time, the drawings are fantastic. It illustrates the way we process information: we don’t draw what we are seeing, we’re drawing what we know.

If my brain sees an eye and nose, it tries to draw its iconic understanding of an eye and a nose, instead of drawing the light and dark right in front of my face. When the drawing to be copied is turned upside down, the brain doesn’t recognize anything, and has no option but to draw the lines it sees. Which is in fact how artists draw.

Photography has some similarities. When we look at the world, we often see things — nouns, collections of objects. We’re seeing with the left logical side of our brains, and it makes photographic composition difficult. Photographers also learn to see with the right side of the brain, the side that doesn’t see bounded things so much as noticing patterns of light and dark.

While we can’t turn our scenes upside down, it’s possible to practice “beginner’s mind” (an idea from Zen Buddhism known as “shoshin“). It refers to having an attitude of openness and lack of preconceptions when studying a subject, even when studying at an advanced level, just as a beginner would.

Composition

In the real world, as you look around, you do not compose little vignettes out of the things before you. There is nothing natural in this activity.

If anything, when you look around, your brain is always creating a sort of internal 3D model of the spatial orientation of things around you. See the bowl on the table: as you move your head and all the objects move around in your visual field — your brain assembles all that data into a model. When I take a picture I’m keenly aware that I have to pick a single vantage point, and from every vantage point I see a slightly different arrangement. By what criterion would I choose one over another?

And now that I’m looking at the bowl, which is the subject I’m interested in, I notice there are reflections in the window on the other side of the room. That stuff doesn’t interest me, but it should, it might be in the frame. As I put a frame around the bowl, thinking about how much context I want, or what various objects might mean in juxtaposition here. So I move a bit here and there and make decisions about having more of this in frame or less of that in frame.

Lenses and Perspective

We’ve all had the experience of seeing something looming before us, snapping a photo, and that big object of our attention is rendered small in frame, way smaller than it felt in real life. This is an optical property of lenses and linear perspective.

Adobe researcher Dr. Aaron Hertzmann has done some brilliant writing on this issue and fully outlines the problem. As he says, “Theories of perception and photography often tend to be all-or-nothing. Either linear perspective and cameras are correct, and cameras don’t lie. Or, there is no objective reality and everything is made-up. The reality is clearly far more complex. Our artwork employs all sorts of complex nonlinear structures, and our brains are able to understand and interpret them.”

So barring new computational photography solutions, a photographer’s best option is to experiment with lenses and focal length in the specific scene you’re shooting and make the determinations in the moment of how to distort the view in a way that “feels” most like what you want to portray. And it further supports the fact that all photography is an artistic creation, a function of the mood and intent of the photographer, and never an “objective” reality.

Candid Photographs

It happens to everyone: something great is going on and you go to take a picture and the moment ends. Pulling a camera out in a social scene is going to change the situation before you, in a very Heisenberg-effected kind of way (which says that the very act of observation directly alters the phenomenon under investigation). Your pictures can feel stiff.

To get around this effect, your observation needs to be limited: As much as cameras certainly change the moment, I believe there can be a short period when a camera arrives in view without causing much scene altering. If the camera stays out longer it has significantly more effect on people in front of it — feeling uncomfortable, feeling watched, or judged.

You are invading the space you’re in, simply by inserting a recording device in there. You’re sitting with friends, with your kids, at work or on vacation: you pull out a camera to capture something, and if you want an authentic scene, you have to be unobtrusive and fast.

These six situations (individually and together) can be frustrating for novices who feel that “my photos never quite capture the scenes as I see them.” It’s not you, it’s me,” er, it’s the camera, the act of picture taking, and overcoming these psychological obstacles is easily done with practice.

P.S. If you enjoy this way of approaching photography I encourage you to take one of my workshops through the Santa Fe Photographic Workshops. There are periodic 3-week online programs (6 sessions), and this August there is an in-person 1-week intensive that should be fun for any creative amateur, maybe if you’ve plateaued, feel like you’re good at picture taking, but want to push yourself. Anyway, Thanks for listening.

About the author: Michael Rubin, formerly of Lucasfilm, Netflix and Adobe, is a photographer and host of the podcast “Everyday Photography, Every Day.” The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. To see more from Rubin, visit Neomodern or give him a follow on Instagram. This article was also published here.

Image credits: Header photo is “Selfie, 1981” by Michael Rubin.