Kodak DCS: Why the Revolutionary Digital Camera System Failed to Catch On

![]()

Sometimes, having an original idea isn’t everything. Innovation can strike at the wrong moment, fizzing out before it has a chance to materialize.

Let’s wind back the clock to find out where the Kodak DCS came from, what it tried to do, and why it never found the success it was going for.

Origins: Steven Sasson and the Digital Camera

The year is 1975. The global camera market is expanding at an unstoppable momentum, powered both by advancements in technology as well as manufacturing.

The 35mm film SLR rules as both the most desirable camera design for consumers as well as the most versatile tool for professional photographers. Higher up the ladder, 120 medium-format film is the benchmark by which image quality is measured among fine art studio photographers and esteemed members of the press.

Though the most recognizable camera companies during this time include mostly Japanese names like Nikon, Canon, Olympus, and Fujifilm, there is one huge American corporation towering above the rest: Kodak.

Not just the world’s most successful and profitable producer of film, darkroom supplies, and equipment, Kodak was also number one in camera sales for most of the 20th century.

They did this not with a professional 35mm SLR system as the mainline Japanese brands, but instead with a whole fleet of inexpensive compact cameras, like the famous Instamatics and Brownies.

The global success of this business strategy gave Kodak a truly enormous R&D budget, a budget that it happily poured into dozens of ‘special projects’ to discover and develop new photographic technologies.

Steve Sasson, at the time a freshly graduated electrical engineer, was one of the hundreds of scientists tasked with such a project. In his case, it was to find a practical use – any use – for the recently invented charge-coupled device, or CCD.

Sasson soon realized that by manufacturing a light-tight box containing a CCD and equipping it with an optical lens, you could emulate the functionality of an ordinary film camera. By hooking the CCD up to a storage medium, the resulting images could be digitally recorded.

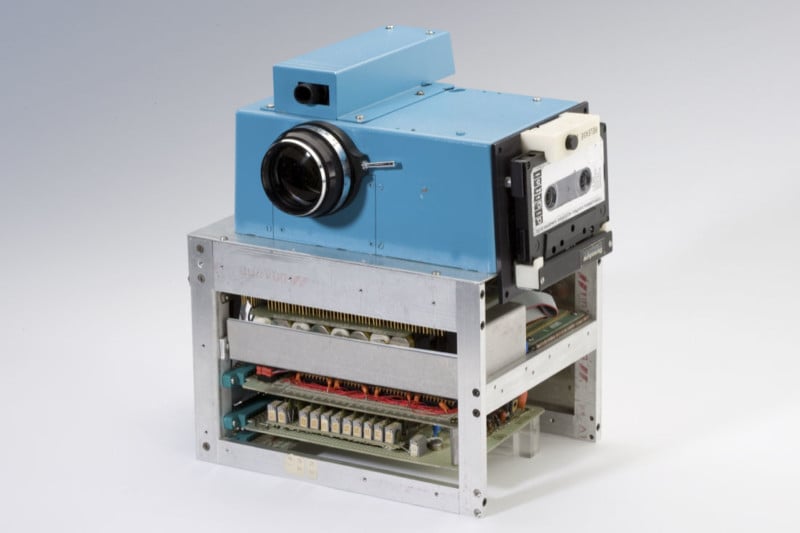

By the end of the year, Sasson had managed to produce a small prototype of his concept. This prototype used a lens from a Super 8 movie camera, ran on nickel-cadmium batteries, and featured an experimental CCD built by the Fairchild corporation that measured 100 by 100 pixels. That’s an imaging resolution of 0.01 megapixels, to use today’s lingo. For storage, Sasson’s prototype used cassette tape.

With no moving parts and performance far beyond the few previous digital camera experiments of the 60s and 70s, Sasson’s device was the first digital camera that was entirely self-contained and that could take, record, and store images without the need for bulky, stationary equipment.

Despite that, his project remained on the fringes of Kodak’s R&D radar, and his invention was hardly publicized at the time.

The First Kodak DCS

Though Kodak was reluctant to acknowledge the huge precedent that Sasson’s invention set, company management was well aware of the future potential of digital photography as a technology.

As the 70s drew to a close, Kodak allocated more and more funds to an outgrowth of Sasson’s original project. As before, the company used CCDs – first those loaned by industrial conglomerates like Fairchild, later ones built in-house by some of Kodak’s many internal divisions – to study and extend the possibilities of recording images electronically.

Sasson himself remained intimately involved in these efforts and was partly responsible for some of the great fruit they would soon bear.

The Megapixel Sensor and Where it Led

By the early 80s, Kodak’s project leaders reached a major milestone. For the first time, they managed to create a functioning CCD imaging system that rendered images at one million pixels.

Despite these monumental advances, Kodak kept its digital camera research under wraps for most of the decade. One reason for this seems rather quaint today: sales of compact film cameras were just far too strong.

Higher-ups at the company feared that the fresh and relatively untested digital technology could backfire and eat up the profits that these more established products were generating.

However, there was also a more grave justification for maintaining all that secrecy. Some US government clients, reportedly including the military, expressed serious interest in the megapixel sensor project and demanded prototypes of digital photo equipment that could be used for espionage and covert operations.

Kodak presented a series of such prototypes starting in 1988 – the first truly portable digital cameras. These were built using modified Canon F-1 bodies hooked up to a large external hard drive wired to the camera.

Each digital camera prototype Kodak produced during the late 80s was relatively unique, and none of them ever achieved serial production.

Only one of these early megapixel Kodaks, the HAWKEYE II, saw real service in a notable role. As part of the STS-44 mission, it was taken up to Earth orbit in 1991 and became the first digital camera ever to take a picture from space.

It’s worth noting that starting with the HAWKEYE series, which was the first of these prototypes to be targeted not just to government agencies, but also to commercial customers, Kodak’s digital cameras received the tagline of “Imaging Accessory”.

Many historians, and even some contemporary commentators felt that this was a deliberate PR move intended to dissuade the public from the notion that digital photography was here to take over pre-existing media entirely. Again, much of this had to do with Kodak’s fears as a business.

The Kodak Professional DCS

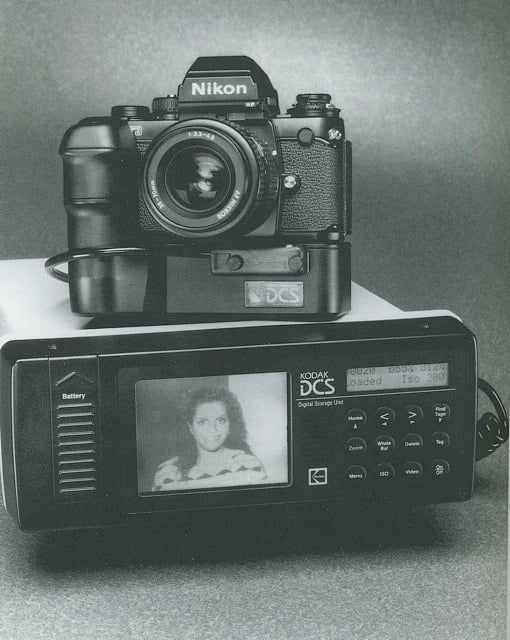

In 1991, the first commercial fruit of Kodak’s series of digital camera prototypes would be presented to the public. Named the Kodak Professional Digital Camera System, or Kodak Professional DCS, it was by our contemporary standards a monstrous and intimidating beast of a camera.

For the early 90s however, it was an incredibly streamlined and downsized, portable digital imaging setup that wowed the press with its capabilities and features.

Like the prior prototypes it was directly based on, the Professional DCS took a Nikon SLR and built a digital imaging solution around it. In this case, Kodak used a beefed-up Nikon F3, Nikon’s third professional single-lens reflex (SLR) camera body.

By taking out the film chamber, replacing it with a 1.3-megapixel digital sensor, and permanently attaching a power winder-data back combo to the body, Kodak achieved all the necessary technical capability without drastically altering the original camera’s ergonomics.

This was important for Kodak, as the intent of the Professional DCS and its planned successors was to win over market share from experienced photojournalists. Making the transition from film to digital easy was imperative in order to convince that demographic that the high price – a cool $20,000 upon launch – was worth paying.

The original DCS was a lot more than just a souped-up, digitized F3 with an integrated motor back, though. Permanently hard-wired to the modified film camera was a huge piece of hardware that Kodak called the DSU, the Digital Storage Unit.

This DSU included an LCD screen for reviewing your images, an internal hard drive for storing them, and a standard SCSI interface for transferring your files to a compatible computer. You could even connect an add-on matching keyboard to edit, transfer, and process your digital photographs “in the field”!

Of course, this system had its limitations. Relying on the hard drive meant that buffer size suffered and real high-speed shooting was very difficult – Kodak claimed a maximum FPS of 2.5, but that was generous. It also made the Professional DCS a true pain to carry around, the Nikon F3 body being about twice as hefty in most dimensions as the analog version and the DSU adding a few dozen pounds’ worth of bulk on top.

Imagine having to carry both your DSLR, a permanently attached battery grip, and a compact printer at the same time, and you might get close to what using the DCS felt like in 1991!

Kodak did try to make this obvious flaw a little bit more manageable for working photographers by bundling the kit with a fitted pouch that allowed you to wear it around your hip or on your back to better distribute the weight. Nonetheless, it’s self-evident that the original Professional DCS was hardly as usable nor as flexible as contemporary film SLRs.

Despite all that, the Professional DCS sold in modest, yet surprisingly healthy numbers. About 1,000 units left Kodak’s dealerships in the three years that it was available on the North American market.

Not a bad performance for an innovative trailblazer based on prototype technology!

The DCS Takes Off

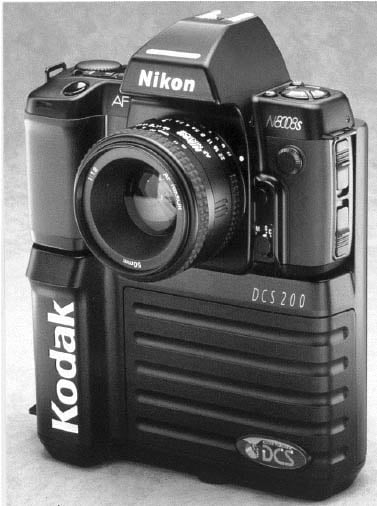

Not too long after the original DCS, Kodak introduced a follow-up model with the Professional DCS 200 in 1992. Instead of a direct replacement, the DCS 200 was intended as a complement to the original DCS (promptly renamed DCS 100, if only unofficially).

Kodak never intended for the DCS 100 to sell in huge numbers, and its designers were well aware of the design’s limitations and prohibitive price tag. Hence, the plan from the very beginning was to release a “little sister” model shortly after the DCS 100 to claim the lower end of the professional photography market and compete where the DCS 100 could not.

The DCS 200 did this in a number of innovative ways. Based on the lower-weight Nikon 8008s instead of the pro-grade F3, it consisted of a power winder, sensor, battery pack, and hard drive compartment just like its sibling.

However, where the DCS 200 differed is in how it arranged these components. Forgoing the separate DSU, the DCS 200 was the first digital camera that neatly integrated all its essential components into one, permanently attached digital back.

It did this by exploiting the rapidly advancing hardware specifications of the time. Downsizing in storage from traditional 3.5-inch to the newly-released 2.5-inch SCSI hard drives freed up tons of internal space and allowed engineers to move the hard drive bay into the camera back itself.

These smaller drives initially couldn’t hold quite the same capacity as their larger siblings, and Kodak’s initial kit topped out at a meager 80 megabytes. At 1.3 megapixels (with a default output resolution of 1012×1524), that means the camera holds enough space for about 50 image files. Not much, but considering the DCS 200 gave the option of near-limitless hard drive upgrades and the use of external storage packs not unlike a DSU for extra space, many customers did not mind.

Instead of lead-acid batteries like the original, the DCS 200 was fed by regular AA alkalines, further saving on weight and bulk while also increasing efficiency.

All these refinements resulted in a camera that cost exactly half of the DCS 100’s retail price at “only” $9,995 while offering much more flexibility and portability to the bulk of professional photographers. Sales more than doubled, indicating demand was building up for the digital revolution.

Further Improvements to the Formula

Throughout the mid-90s, Kodak would dish out further DCS models at a rapid rate. There was the AP NC2000, designed for press photographers and released in 1994. As the name implied, AP News sponsored this model and provided it as a standard kit to many of their staff.

The “News Camera 2000” (yes, that’s its real name) would play a significant role in ushering in the age of digital news photography, despite its modest production run of about 500 units.

Other standout Kodak DCS cameras from this time period would include the DCS 460, part of an all-new 400-series lineup. While most of these models were sort of refreshed previous-gen DCSes, now based on the Nikon N90 body (also known as F90 in some regions), the flagship 460 was different.

It sported a newly-developed high-resolution sensor that topped out at a radical six megapixels, offering image files measuring 2036 by 3060 pixels across. Instead of hard drives, the 400 series also introduced the use of much more compact and convenient flash cards, initially in PC format.

This sensor cemented Kodak’s image as the leader of the pack when it came to digital camera development, and it sold well: The DCS 460 alone shipped over 5,000 copies, the entire 400 series at least twice that much.

The Kodak-Nikon Relationship

One curious thing to note about these early Kodak DCS cameras is how exactly they related to the Nikons that they were so obviously based on. Because Kodak did not enter into an official partnership with the Japanese giant until later on, all the cameras it used for conversion into digital devices were bought by the company on the retail market.

“I believe [Nikon] were surprised when we announced the DCS,” says James McGarvey, who led the development of pro Kodak cameras for 17 years, in an interview with NikonWeb.com. “We bought F3’s through normal dealers (I don’t remember who), and since the quantity was small before the product launch, I doubt if Nikon was alerted to anything ahead of time.

“I remember that we were packing the F3 back door in the kit with the DCS, since we had it and a user might want to use the body with film at some point. Nikon told us we couldn’t do that as we were not an authorized dealer. We could incorporate the F3 in our product, of course, but not ‘resell’ cameras!

“Generally, though, I believe Nikon was happy with the situation, since they were selling F3’s and the first commercial digital camera was carrying their lens mount. I don’t remember any complaint other than the door issue.

“I don’t think we told Nikon ahead of the DCS 200 launch, either, but they did help us with the following cameras.”

As they were left mostly unaltered, Kodak’s Nikon-DCS cameras all still sport the “Nikon” nameplate on the top of the reflex mirror housing. To avoid possible brand identity issues, Kodak began using a very large, white “KODAK” print on the digital backs and grips of all the DCS cameras starting with the DCS 200.

Even as the official Nikon partnership went ahead, future DCS cameras would continue being physically labeled in the same way, indicating their origins: camera bodies by Nikon, sensors and digital tech by Kodak.

Toying with the Canon EOS System

At a certain point, Kodak realized that tying their DCS line exclusively to one camera brand was a risky move. Hence, between 1995 and 1998, they went on to release a line of cameras in parallel to their 200 and 400 series using the same digital backs but connected to Canon EOS bodies.

Against expectations, the EOS DCS cameras sold just as well as their Nikon-based counterparts. Part of the reason for that might have been that they were developed from the ground up in cooperation with Canon, featuring custom firmware and certain hardware optimizations that the original DCSes lacked.

The peak of this Canon-based model line came in 1998 with the DCS 520. While not offering the world-class high resolution of the previous DCS 460 at only 2 megapixels, it seamlessly and very ergonomically integrated its digital back into the camera body, also offering top-flight burst shooting performance at over 3.5 frames per second.

Prized among news photographers of the time, it retailed for $14,995. In opposition to previous DCS models, the camera was triple-branded: “Canon” on the prism, “KODAK” on the grip, and “KODAK PROFESSIONAL DCS 520” where the digital back connected to the camera near the tripod mount.

Unlike the ever-evolving partnership with Nikon though, Kodak wouldn’t stick with Canon for long. The Japanese company was the one to cut ties according to most reports; arguably, they were planning their own entry into the DSLR field soon and didn’t want to rely on third-party tech to do so.

Enter Nikon D1

In 1999, a new challenger dramatically entered the field that Kodak had single-handedly dominated for an entire decade. Instead of a radical newcomer like Olympus or Pentax as many analysts had predicted, the first non-Kodak, independently developed digital SLR system came from none other than Nikon themselves.

Depending on which stories you believe, this radical upset was either a carefully planned succession, agreed upon by Kodak and Nikon behind the scenes long beforehand, or a dramatic stab in the back.

Either way, the Nikon D1 made serious headlines when it came out. Here you had a camera that required absolutely no learning curve from the professional photographer – being almost identical in dimensions to the film-based F5 – while also offering compatibility with all existing Nikon lenses, accessories, and software.

Furthermore, the D1 offered performance previously unheard of in digital cameras. Its 2.7-megapixel sensor was good for 4.5 FPS of burst shooting at a record-setting shutter speed of up to 1/16,000s, ticking all the boxes for press photographers of the time.

Kodak did actually have a competitor cooked up just in time for the D1, further indicating that this sudden move was anything but unexpected. The Kodak Professional DCS 600 series, headed by the 660 model, was released within a few months of the D1 and was likewise based on the Nikon F5.

However, its body was heavier and bulkier compared to the D1. And even though it used the higher-resolution, award-winning 6MP sensor from the 460, the DCS 660 stood no chance in direct competition with the D1, which cost a third as much at only $4,999 compared to the $14,995 MSRP of its very similar Kodak sibling.

The DC: Doing What Kodak Knows Best

In parallel to the DCS 400, 500, and 600 models, Kodak also spent some of its considerable budget on the development of more consumer-oriented digital cameras.

Point-and-shoots and disposable cameras were selling in crazy numbers throughout the late 90s, so much so that Kodak was actually recording record growth and profits from 1995 to the year 2000, despite the immense cost of its digital camera research program.

This made the company highly optimistic about the potential of cheap, easy-to-use, mostly automatic digital cameras for amateur photographers.

Almost all of Kodak’s entries in this field were branded DC, simply Digital Camera. The entire lineup, which included over twenty different models, was released at a rapid pace between late 1995 and 1998.

The bottom-line DCs, like the DC10 and DC20, sported sensors with less than half a megapixel in resolution, in addition to very basic prime lenses with relatively slow apertures. On top of that, they only included a minuscule amount of flash memory for saving about a dozen pictures at a time. And you had to transfer these to a computer to view them since the cameras themselves came without any LCD screens.

Of course, the point of these entry-level cameras was to severely undercut the competition in terms of price. And that the DCs did, coming in at an MSRP of as little as $365 for the bottom-level DC20, at a time when there were few serious competitors in the digital field far below $500.

More advanced models, such as the DC200, offered megapixel sensors, rear LCDs, and additional controls like AE lock and manual focus override.

Ultimately, what doomed the Kodak DC series is that, unlike with the DCS, the company couldn’t rely on many years of effective monopoly to rule the market.

Before long, dozens and dozens of competitors sprung up all over the low end, from established manufacturers like Nikon and Canon as well as electronics companies that previously had little of a connection to photography, like JVC, Panasonic, and Sony.

This tight competition eventually swallowed the Kodak DC. Even after a rebrand to Kodak EasyShare during the early 2000s, Kodak’s entry-level digital cameras didn’t manage to turn their fortunes around.

The Demise of the DCS, and Kodak With it

Following the release of the Nikon D1, the Kodak Digital Camera System entered a period of decline that it would never recover from.

On paper, this might come as a surprise, since Kodak did not choose to swiftly abandon their product in the face of tough competition. If anything, the opposite was the case.

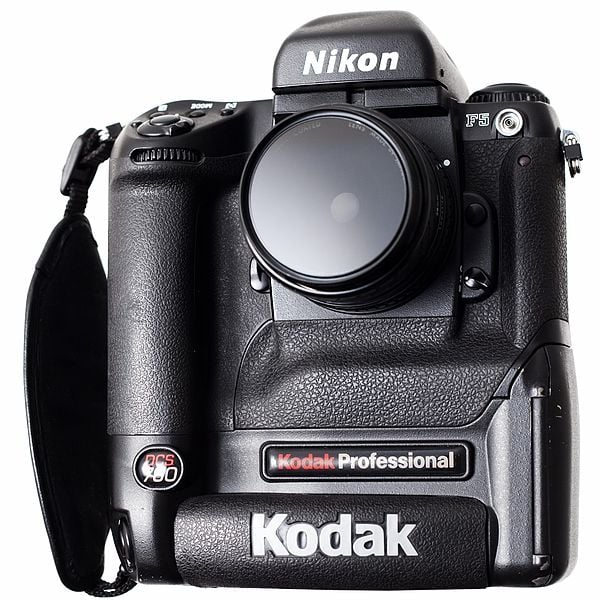

In 2001, the company released the Kodak Professional DCS 700 series, championed by the DCS 760. Though decked out with brand-new digital guts on the inside, the 700 was built out of the same Nikon F5 bodies powering the previous model.

Starting at $4,995, with a price tag of $7,995 for the top-of-the-line DCS 760, the 700 range proved popular both with photojournalists as well as wedding and event photographers. The F5 body was, by the turn of the century, an accepted industry standard, and Kodak’s electronics traded blows fairly with Nikon’s steadily improving D1 series.

Even in terms of price, the company managed to compete, though Nikon’s options were still the more affordable of the two, strongly leading in sales as a result. And increasingly, digital shooters wondered why they should spend thousands of dollars more for a camera that was bulkier than any D1 whilst sporting the exact same button layout, lens mount, and “Nikon” script on the pentaprism housing.

Canon Enters the Ring

Further complicating things was the arrival of Canon’s first DSLR flagship that same year, the EOS-1D. Sporting much faster burst shooting of up to 6 FPS and better high-ISO results than the Kodak while also being less bulky, it managed to steal significant amounts of customers away from the DCS brand.

Kodak knew that they were facing an uphill battle trying to face off against Nikon and Canon as well as other professional camera brands preparing their entry into the digital sphere. Hence, they quickly prepared a follow-up flagship model that would vastly outperform anything the competition could offer, in the hopes of retaking the proverbial crown and guaranteeing upward sales momentum for the DCS line.

The Kodak Professional DCS Pro 14n: Last of Its Kind

That new flagship came in late 2002 before the dust of the DCS 760’s release had even fully settled yet. In a break with prior tradition, the camera was called the Kodak Professional DCS Pro 14n.

The timing of the Pro 14n’s release was near-perfect, ensuring that it would land on store shelves with a bang. Canon had just brought out their most serious contender in the pro digital SLR field yet, the EOS-1Ds.

Upon release, the Canon stole the limelight. Its high-resolution CMOS sensor was unlike anything else digital camera reviewers had handled before, and it offered both crisp sharpness as well as low noise even in tricky lighting conditions. It was also the first production DSLR in the world to sport a full-frame sensor, offering the same perspective and depth of field as traditional 35mm film.

Though it couldn’t shoot as fast as the original 1D and retailed at a much higher $8,999 upon launch, both Canon and the press felt that this was justified given the Canon’s class-leading performance and high-tech build.

Nikon, surprisingly, lagged behind considerably. Offering no major releases for 2002, the company kept relying on its now somewhat long-in-the-tooth D1X and D1H bodies.

This was truly the perfect environment for Kodak to come in, burst onto the scene, and change the paradigm entirely in its favor. In a way, that is what the company achieved with its Pro 14n.

Offering a state-of-the-art CMOS full-frame sensor developed in-house, the DCS Pro managed to outclass its Canon rival by a solid three megapixels for a total count of 14, a world record at the time for a production DSLR.

The body was much sleeker than any DCS camera before it, being based on the Nikon F80. Using advanced manufacturing techniques and modifying the original camera body far more than on previous models, Kodak managed to considerably slim down the DCS, bringing it solidly in line with the competition.

Perhaps as a deliberate jab at their former partner, the Kodak DCS Pro 14n was also the first in the series to feature no Nikon or any other third-party branding anywhere on the body.

But the most stunning aspect of the DCS Pro was not the fact that a gigantic corporation like Kodak had managed to produce such a machine. Rather, it was that they could justify selling it at such a low price.

At $4,995, the Pro 14n’s MSRP undercut both Canon’s and Nikon’s offerings by literal thousands, ensuring that all eyes were on Kodak by Christmas of 2002.

The only problem? Christmas came and went, and the shiny Kodak was nowhere to be found. Due to problems in manufacturing and quality control, the first batches of the brand-new model wouldn’t actually be sold until well into the following year.

By that time, Nikon had already prepared their next flagship, the D2H. Packing a crop sensor optimized for speed rather than resolution, the D2H became a runaway hit with the demographic that had originally been the most loyal source of sales for Kodak DCS cameras – sports shooters and press photographers.

When it did arrive, the Pro 14n had to compete instead with the Canon EOS-1Ds among portraitists, and architectural and studio photographers. In that field, the Kodak’s value for money was highly praised, as was the stunning resolution from its full-frame sensor.

However, the Canon didn’t lag far behind, and it offered those enticing three whole frames per second of continuous burst shooting. The Kodak topped out at 1.7fps with a very high power draw, a dealbreaker for plenty of wedding and event photographers. Low-ISO performance also lagged behind the competition despite the innovative sensor technology.

In the end, the DCS Pro 14n failed to grab the market share that Kodak had intended it to, and the decision was made to discontinue the whole DCS line as a result.

Kodak would actually end up releasing two more models afterward in 2004, the DCS Pro SLR/n based on a Nikon F80 and the Kodak DCS Pro SLR/c based on the EF-mount Sigma SA9. Though these cameras addressed many of their predecessor’s shortcomings, in particular by using a revised imaging sensor that offered far better low-light performance, the damage had already been done.

Like the 14n, the Pro SLR/n and Pro SLR/c only sold in modest numbers and did not see more than a short year of production.

Kodak’s Downfall, Post-DCS

As the DCS vanished over the course of the 2000s, Kodak lost the one chance it had at a pole position anywhere in the camera market. With the digital revolution accelerating, sales of its once ubiquitous film-based point-and-shoots were drying up.

Instead of Brownies and Instamatics, young people were increasingly going for Panasonic Lumixes, Canon PowerShots, and others. On top of that, film itself – Kodak’s main business for the past century – was losing market share at a rapid rate.

All of these factors combined with the 2007-08 financial crisis made for a perfect cocktail of disaster for the once-invulnerable photographic giant. Kodak would file for bankruptcy in 2012, emerging in the year after as the two-faced shadow of its former self that we recognize it as today.

While Eastman Kodak continues to manufacture film for the motion picture industry, the UK-based Kodak Alaris tries to continue the former company’s legacy in photographic film supplies.

The idea of designing another range-topping camera system, let alone one that could compete with the best of Canon, Nikon, or Sony, is not even anywhere near the table anymore.

What We Can Learn From the Fall of the DCS

Though Kodak’s Digital Camera System was the first of its kind, combining tried-and-true Nikon optics and ergonomics with stellar digital sensor technology for its time, it did not become the smash hit that many continue to say it deserved to be.

Initially, it seemed a wise choice for Kodak to build the DCS out of retail Nikon camera bodies, a design strategy that would be absolutely unthinkable today. While it guaranteed that Kodak did not have to design a costly proprietary lens lineup for its cameras, it also meant that the company eventually ran itself into a dead end.

As soon as Nikon and later Canon and others began making their own DSLRs, the flaws of the DCS stuck out to the public.

With each of its many subsequent iterations, the DCS struggled with inherent flaws or disadvantages against its contemporary rivals. Perhaps because Kodak spent the vast majority of its R&D budget on the sensor technology, which was indeed cutting-edge, quality-of-life issues such as ergonomics, battery life, and day-to-day usability did not receive the same kind of treatment as they did from others.

Today, much of the technology we use in our DSLRs and mirrorless cameras can be traced back to the advancements of the Kodak DCS.

In fact, if it hadn’t been for the original Professional Digital Camera System, it’s hard to imagine that sites like PetaPixel would exist today!

For that reason, it’s important to remember everything that the Kodak DCS did right and the pioneering influence it had on the early digital camera landscape. At the same time, the story of the DCS should also serve as a fair warning to future generations of engineers, camera designers, and of course manufacturers and photographers themselves.

Image credits: Header photo © Kodak