Nat Geo ‘Pictures of the Year’ Celebrates Photography’s Enduring Impact

![]()

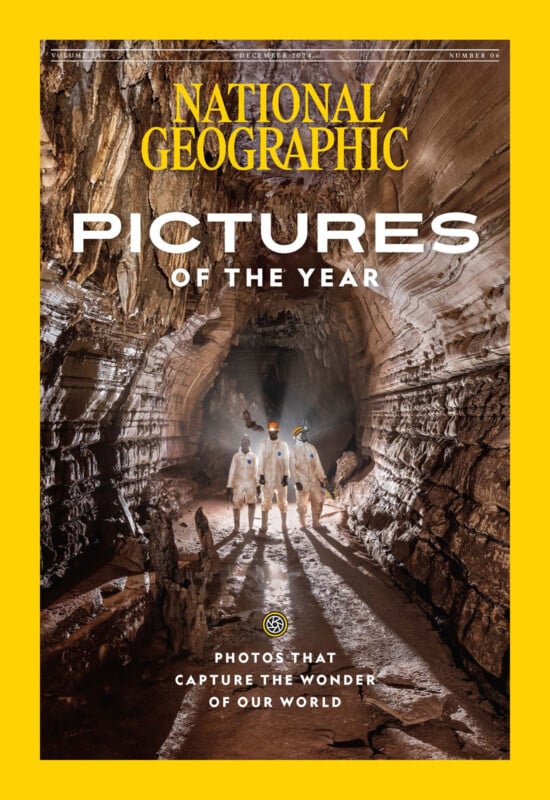

National Geographic‘s annual “Pictures of the Year” issue celebrates the incredible adventures that Nat Geo photographers embark on each year and the remarkable, vital photographs they bring back.

Like last year, PetaPixel chatted with National Geographic Director of Integrated Storytelling Sadie Quarrier about “Pictures of the Year.” Additional topics discussed include the state of photography, and the vital work photographers do to tell the world’s most important stories.

Nat Geo‘s Team Sorted Through 2.3 Million Photos This Year

Last year, Quarrier and her team had the daunting task of filtering through two million photos to make its final selection. This year, the team had 2.3 million images to work through, eventually settling on 20 to highlight in the “Pictures of the Year” issue. As Quarrier explains, it’s a team effort.

“I wouldn’t be able to do this without the help of the talented Photo Department staff who are editing through epic numbers of images shot on various assignments that they’re responsible for. Beyond the photo editors, there were at least twenty others involved in pulling this cover story together: a photo coordinator, designers (print and digital special build), writer, text editor, copy editor, researcher, color correction experts, programming officer, project lead, Editor in Chief, and more.”

‘You think maybe it’ll finish in 10 minutes,’ photographer Babak Tafreshi says, but their takeoff ‘continues for two hours.’ | Photo by Babak Tafreshi for National Geographic)

As for her essential role, Quarrier says she looks beyond the expected criteria, like great light, compelling compositions, and powerful moments, and seeks out “surprising and arresting images that make me want to know more.”

“The final choices are the ones that were still resonating with me weeks later,” she says. “They sparked my curiosity, surprised, delighted, or enlightened me in some way.”

‘Pictures of the Year’ Celebrates Images for Different Reasons Than Typical Issues

National Geographic features many beautiful photographs throughout the year. Photography is a critical part of publication, and it has always been. However, in typical situations, the images support a story or are presented as a large series. For “Pictures of the Year,” an image must stand on its own.

“For ‘Pictures of the Year,’ first and foremost, the image has to be unique, surprising, and compelling. If there’s deeper meaning and/or an interesting backstory that gives the image significance beyond the visual aesthetic, it becomes a much richer candidate,” Quarrier says.

I always consider each picture on its own, removed from the context of the story it was selected from, and ask myself if it stands on its own. By contrast, when editing for our traditional stories, we need a range of images to weave a strong visual narrative, so not every picture has to be, or is deserving of, center stage.”

The Changing Landscape of Visual Storytelling

While “Pictures of the Year” always puts still photography on a pedestal, National Geographic‘s broader approach has become more multimedia in recent years. The company is heavily involved with television content on cable and streaming platforms, and even stories on the website have become more reliant on dynamic presentation.

Quarrier believes this changing landscape is “one of the most exciting aspects of visual storytelling today.”

“I love that we can share our stories–captured in multiple mediums — on so many platforms and thus cater to a wide range of audiences. I treasure our print magazine, and this ‘Pictures of the Year’ issue will sit on my coffee table for the next year. But I also love seeing our digital version of these images come to life on the screen as you scroll through.”

Speaking of these digital versions, there is much to love this year. Beyond the images being presented in beautiful, vibrant glory, there are even opportunities for readers to go “behind the scenes” for different photos, like a look at how acclaimed photographer Babak Tafreshi captured a fantastic image of bats in Texas (seen above) and how photographer Prasenjeet Yadav used remote cameras to photograph elusive black tigers in India. These unique stories behind the featured photos, including some behind-the-scenes videos, provide valuable insight into the technical challenges and artistic decisions photographers make in the field.

“Our video and social teams combined behind-the-scenes videos of the photographers in the field with their final images to create really insightful, fun mini experiences for four of our images. This mixed media approach gives our audience deeper insights into how a photograph came together. It’s personal and works well on social platforms,” Quarrier adds.

While video is, as she puts it, “very seductive,” Quarrier will “always deeply value the ‘moment’ when a photographer has captured something really special, stopping time.”

“There’s a reason they call them enduring moments.”

National Geographic and Conservation

Many ecosystems around the globe are in serious trouble, and photographers have unique skills to help tell vital stories and, hopefully, help stem the tide of destruction.

“For more than 100 years we have used strong visual storytelling to inform our audiences and bring conservation issues to the forefront. We have long banked on the fact that compelling images are an excellent way to make audiences care, open minds, and perhaps even inspire action,” Quarrier says.

Many of the “Pictures of the Year” selections are related to conservation and the health of our planet and its inhabitants. For example, Ami Vitale’s image of a person holding a rhino fetus is a particularly impactful image deeply tied to conservation issues.

“I’m very moved by National Geographic Explorer Ami Vitale’s iconic image of a researcher’s blue gloves holding a 70-day-old rhino fetus, the first ever conceived through in vitro fertilization,” Quarrier remarks.

I’m mesmerized by this tiny creature, and there’s an incredible backstory — only two adult northern white rhinos remain on the planet and both are females.”

An international team of researchers in Kenya is trying everything they can to save this species from extinction. While it’s a bittersweet image, I also very much see it as a future breakthrough moment for science and a hopeful image for a species and all of us! The symbolism of the weight of a species being held in a researcher’s hands is not lost.”

Quarrier adds that Vitale and her work on the rhino story will be featured in an upcoming Nat Geo show, “Explorer: Rhino Resurrection”.

National Geographic‘s ‘Pictures of the Year’ Show the Incredible Impact of Photography

“I thoroughly enjoy curating a terrific set of images to make this annual package as great as it can be,” Quarrier concludes. “I want people to be transported to places and situations they would never normally see. The world and our daily lives can be kind of stressful at times, and I hope these images offer a nice reprieve.”

The complete “Pictures of the Year” story is available online and in the December issue of National Geographic, available on newsstands now. Six of the images are also detailed through a special behind-the-scenes digital experience.

Image credits: All photos courtesy of National Geographic. Individual photographers are credited in the image captions.