The Most Influential Women in Photography History

![]()

As with many fields, photography has not always given women their due. But in truth, photography would not be what it is today without the pioneering work of countless women.

Diane Arbus and Sylvia Plachy serve as pioneers of street photography. Meanwhile, Margaret Bourke-White and Lee Miller brought back images from World War II. Sally Mann and Vivian Maier captured the intimacy found in homes and families. The likes of Dorothea Lange, Nan Goldin, Cindy Sherman, and Carrie Mae Weems have served as documentarians and activists who have shared harsh realities and whose work has led to widespread change. It’s possible to trace a line from the pioneering work of Anna Atkins to the living legend that Annie Leibovitz has become, following a string of women who have forged paths even before they were allowed to do so.

This list, though certainly not comprehensive, is a testament to the work many women have contributed to photography.

Diane Arbus

Thanks to her illustrious and fearless career, Diane Arbus could be considered the mother of street photography. Arbus embraced grit before grit became passé. It’s why her career looms over the history of photography, even serving as inspiration for her counterparts throughout this list. Annie Leibovitz told The New York Times she found Arthur Lubow’s biography of Arbus “riveting and illuminating.”

Arbus pioneered flash photography, using it to highlight her subjects. Her street photography combines posed environmental portraiture while evoking candids, making her work stand out among the genre.

“Some people like to think of [Arbus] as cynical,” PetaPixel quoted photographer Edmund Shea saying. “That’s a total misconception, she was very emotionally open. She was very intense and direct, and people related to that.”

In her personal life, she and her husband Allan Arbus were a photography power couple, but she still stands tall behind the lens on her own. She suffered from depression and ultimately died by suicide, but her legacy lives on.

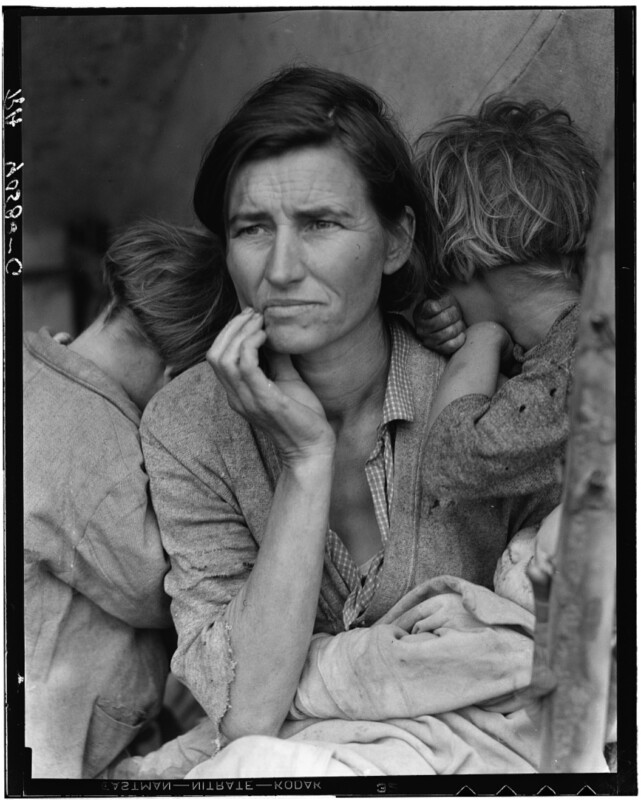

Dorothea Lange

Dorothea Lange is most known for her work capturing a broken American spirit during the Depression Era. Arguably her most famous photograph, “Migrant Mother,” depicts a matriarch, worry written across her face and surrounded by her family. A 1950s-era gelatin silver print sold for $31,250 in a 2022 auction. Many of her works are on view at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. now through Sunday, March 31.

Lange, born in New Jersey and raised in New York City, settled in California after college, where much of her photography career blossomed. Though known for her rural scenes, Lange also cut her teeth on the streets of San Francisco, capturing people contending with illness, homelessness, and poverty. She then focused on capturing the stories of farm workers before spending her time in the 1940s photographing the U.S.’s Japanese internment camps. Never one to shy away from the dark parts of American history, Lange also photographed striking laborers, life under Jim Crow laws, the lives of Indigenous people, and took portraits around the world.

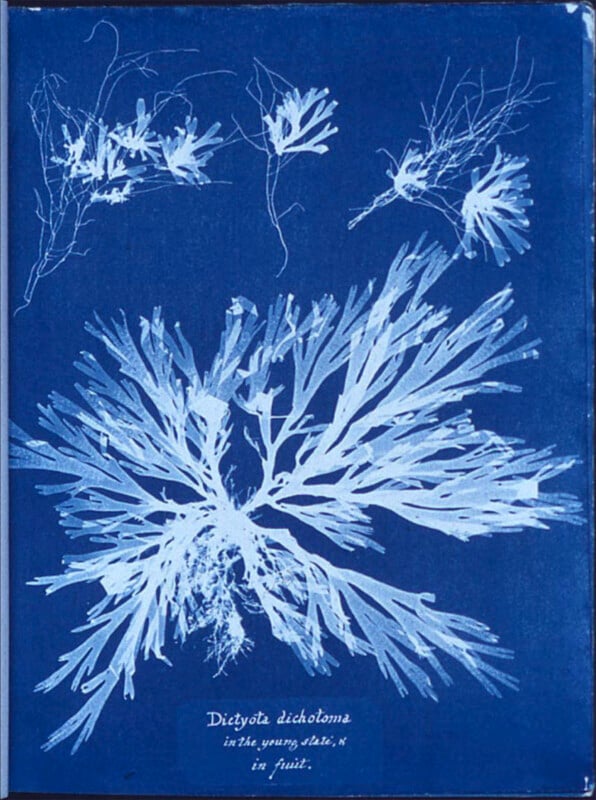

Anna Atkins

Working in the mid-1830s, Anna Atkins was a pioneer on multiple fronts, both in photography and science, specifically in botany. Although the work she’s famous for didn’t involve a camera, she is often thought of as the first female photographer, pushing the boundaries of a medium that was only recently invented.

Atkins relied on the cyanotype process, a cameraless method of making images that involves placing objects directly on a material with a light-sensitive coating. She combined this photographic method with her work as a botanist, creating simple yet beautiful cyanotypes of her collection of British algae. Eventually, Atkins self-published her images in “Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions,” which was the first book illustrated with photographs. She went on to release multiple editions and expanded her subject matter to flowering plants, feathers, and more.

Atkins’s photographic work was groundbreaking not only because it used a new medium but also because it established photography as an accurate scientific tool. She operated in not one but two male-dominated fields at a time, pushing boundaries that were limiting women’s participation in photography and science.

Margaret Bourke-White

Like many others included here, Margaret Bourke-White pushed past boundaries, redefining what women could. She has many firsts to her name, including serving as the first female war correspondent accredited by the military, the first woman allowed to work in combat zones during World War II, Life magazine’s first female photographer, the first Western photographer permitted into the Soviet Union, and the first photographer for Fortune.

Bourke-White’s career was varied but began in industrial and architectural photography, where she, in part, aimed to end the bias against women in Cleveland’s steel mills. In the 1920s and 1930s, like Dorothea Lange, Bourke-White captured images of the Dust Bowl and Great Depression, creating iconic images that became synonymous with that period. This work elevated the status of documentary photography to an art form.

Throughout her career, Bourke-White photographed many pivotal moments in the 20th century, capturing unique insights into historical events and figures. These ranged from the Great Depression to the horrors of the Holocaust and World War II and documenting the iconic photo of Mohandas K. Gandhi in 1946. She broke gender barriers while setting new standards for war photography and photojournalism.

Nan Goldin

Some photographers remind people why the medium is so important, placing the need to document life at the very forefront. Nan Goldin is one of them. Goldin was a crucial documentarian of the LGBTQIA community as HIV/AIDS ravaged its members in the years after the Stonewall Riot rallied them. She further captured the effects of the opioid epidemic, becoming an activist for the cause as a founding member of P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) and coming forward with her addiction struggles.

“I took the pictures in this book so that nostalgia could never color my past. I wanted to make a record of my life that nobody could revise: not a safe, clean version, but instead, an account of what things really looked like and felt like and smelled like. I don’t think I could, at this age and in this body now, live the life that I lived then. It took a certain level of fearlessness, a wildness, quick changes—of clothes, of friends, of lovers, of cities,” Goldin said in an essay for Aperture regarding her 1986 photobook The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. The same can be said for her work as a whole.

Most recently, Goldin, along with fellow listee Vivan Maier and two other noted female photographers, was inducted into The International Photography Hall of Fame, or I.P.H.F., during the 2023 awards.

Cindy Sherman

Cindy Sherman is best known for playing multiple roles, both in front of and behind the camera. Through her photographs, she transformed herself into an array of characters that critique societal and cultural expectations of gender, identity, and the role of images in contemporary life. She distinguished herself from other photographers for her unique use of self-portraits, posing in front of her own camera for staged photographs.

Sherman’s best-known series, “Untitled Film Stills,” blurred the lines between fiction and reality, questioning the construct of identity. This body of work, in particular, made her a cornerstone of postmodern art. In her self-portraiture, she crafted scenes that resembled film stills or historical portraits without ever revealing her true self. These self-portraits explore themes surrounding the objectification of women, the stereotypes perpetuated by media, and the fluidity of identity.

Just like Madonna, Sherman continuously reinvents her image and engages with contemporary issues, keeping her relevant and influential to this day. Her work has inspired countless others to explore and critique societal norms, explore the complexities of identity, and examine the power dynamics in visual culture.

Sally Mann

There’s no denying the impact of Sally Mann’s work on the field of photography throughout her more than four-decade career. Her images capture intimate, emotional moments in a haunting, ethereal manner. She developed her distinctive style using large-format cameras and analog processes, including wet plate collodion.

Although she has produced many impactful works throughout her four-decade career, her 1990 series “Immediate Family,” which documented her three children, propelled her career and garnered widespread recognition. The nudity and provocative poses proved polarizing and sparked debate, but they showed Mann’s artistic fearlessness and dedication to creating thought-provoking images.

In her photographs, Mann tackles challenging themes surrounding family, childhood, mortality, and the landscape of the American South. In the introduction of “Immediate Family,” Mann wrote that “many of these pictures are intimate… but most are of ordinary things every mother has seen. I take pictures when they are bloodied or sick or naked or angry.”

Beyond their stunning beauty and mastery of light and composition, Mann’s images raise worthwhile questions about artistic license and the complexity of public versus private photos. The questions Mann has posed through her photography remain as vital today as they were then.

Lee Miller

Though she began working in front of the camera as a model, Lee Miller is best known for her work as an indomitable photojournalist. She trained under nearly impossible circumstances — in London and Paris during the outset of World War II.

Miller photographed the Blitz of London and witnessed human rights violations committed by the Nazis. She positioned herself at the frontlines to capture necessary images at a time when female war correspondents were not allowed to do so.

But if her arc as a model turned war photojournalist doesn’t make it clear Miller lived many lives, her work does. Miller’s photographs also span the portraiture of other artists, film stars, and the fashion industry in the years after the world. Miller lived in numerous cities, including New York City, London, Paris, and Cairo. She also collaborated and crossed paths with the likes of Man Ray, Pablo Picasso, and Jean Cocteau.

Miller defied convention and expectation at every turn. In 1945, she took a self-portrait in Hitler’s bathtub, coincidentally on the same day as his suicide, and slept in his bed. This was recaptured by fellow listee Annie Leibovitz for Vogue, referencing the upcoming biopic on Miller starring Kate Winslet, which is slated for theatrical release in September.

Carrie Mae Weems

Carrie Mae Weems has a career spanning five decades in photography, video, installations, and public art campaigns. Her innovative storytelling technique expanded the scope of photographic art, pushing the boundaries of the medium and creating layered narratives that invite viewers to engage with broader social and historical dialogues.

Weems’ art brazenly calls attention to historical biases that shape our perceptions and guide our actions, exploring concepts related to African American identity, culture, and history. For example, in her “Kitchen Table Series,” she combines text and images to delve into the complexities of the personal and political realms of the lives of Black women. This series, along with much of her other work, portrays subjects that are traditionally marginalized in mainstream art.

Beyond her art, Weems also has an upstanding reputation as an activist and mentor. In 2002, she co-founded Social Studies 101, a program to mentor local youth in creative professions. She has also collaborated with groups on anti-violence campaigns in response to gang violence.

“There are days, especially when we’re editing, when we just leave the studio in a shambles, or we’re just too mentally exhausted to look at another image of someone being shot,” Weems explained in an interview with The New York Times. “But as much as I’m engaged with it, with violence, I remain ever hopeful that change is possible and necessary, and that we will get there. I believe that strongly, and representing that matters to me: a sense of aspiration, a sense of good will, a sense of hope, a sense of this idea that one has the right, that we have the right to be as we are.”

Annie Leibovitz

Annie Leibovitz remains a go-to for high-profile portraits. In recent years, she’s photographed everyone from Olympic gymnast Simone Biles, soccer players Lionel Messi and Christiano Renaldo, Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, and the late Queen Elizabeth. She’s behind numerous iconic Vogue covers and campaigns for luxury brand Louis Vuitton. Though she’s faced controversy, especially for her portraits of people of color, Leibovitz is considered one of the most successful photographers of all time, at least according to The New York Times.

Lately, Leibovitz seems more focused on passing on her education both through her first-ever Master Class and through a recent partnership with Ikea. Leibovitz contributed the “At Home” photo series for the Swedish furniture company, which extended to a mentorship with six young photographers.

Considering Leibovitz remains as busy as ever, her career is a work of living history.

Sylvia Plachy

Though born in Budapest, Sylvia Plachy is a New York City photographer through and through. Her street photography of the famous and infamous metropolis has earned her recognition through publication in outlets like The Village Voice, The New Yorker, New York Times Magazine, and Fortune.

“For many years, she relied on her eyes to fill in where she didn’t understand the language,” the U.S. Department of State says in her listing on Art in Embassies.

Her work documents New York as an ever-evolving city throughout the decades, capturing everyone from the wealthy elite to often forgotten sex workers in equal measure. Her weekly column for The Village Voice, “Unguided Tour,” was a cultural knockout for the photographer, capturing the interest of locals and fans worldwide. Her work from the column is on display now through April 14 at the Brooklyn Public Library’s Central Branch as part of the exhibit “It happened in New York: Photographs by Sylvia Plachy.”

Vivian Maier

As is the unfortunate case of many artists, especially those who are women or non-binary, Vivian Maier didn’t see a great deal of recognition for her work when she was alive. Thankfully, the years since have at least shined a great light on her photography. Maier was adept at street photography and her turn as a “nanny photographer,” capturing the private moments within the household where she worked. No matter the setting, Maier was a master of evoking the human spirit in her photographs, a skill that has forced history to reexamine her artistry.

Upon her death, more than 150,000 of her photographs were found, including those she took of suburban life, which had not been previously shared. This led to a legal battle over ownership that ultimately opened up accessibility to a great deal of Maier’s previously unseen work.

Her work has been explored in the documentaries Finding Vivian Maier (which was nominated for an Oscar) and another from B.B.C. . She and fellow listee Nan Goldin were inducted into The International Photography Hall of Fame, or I.P.H.F., during the 2023 awards, along with two other distinguished female photographers. Additionally, her work will be on display at the photography museum Fotografiska New York beginning May 31.

Featured image credits: The portrait of Annie Leibowitz in the featured image, seen at the far right, was captured by photographer Robert Scoble.