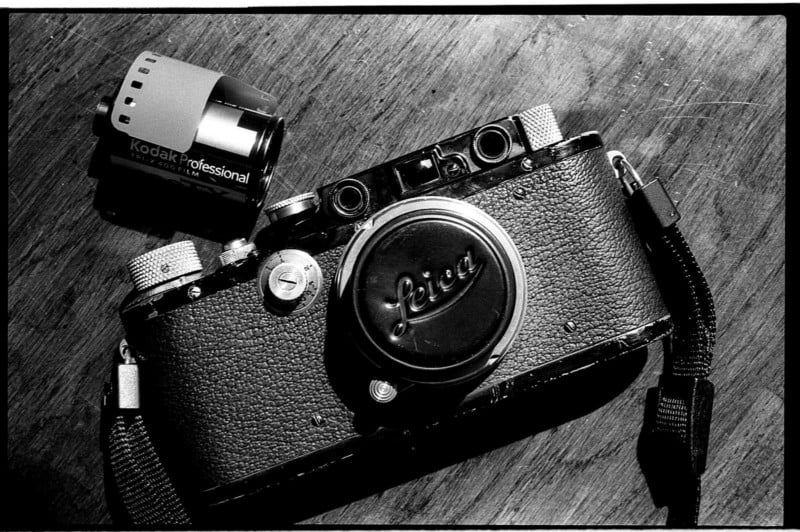

Barnack Quirks: An Intro to Shooting with Early 35mm Leica Cameras

![]()

If you’re primarily a digital photographer with an itch to return to your roots or a film photographer who appreciates the tech as much as the image, Barnack Leica’s are a fun way to see what it was like to take photographs almost a century ago with one of the world’s most innovative and celebrated camera designs.

Barnack Leicas offer an invaluable perspective on photography from the obvious historical standpoint but also in terms of internalizing the fundaments of photography – which have never changed.

What I and many others find particularly amazing about these little wonders is that they set the standards for what we expect modern cameras to be. Therefore, using a Barnack can often feel oddly intuitive.

The reward for using these ancestral relics can often be some very emotive and surprisingly effective photography.

All is not roses and sunshine with Leica Barnacks, though. Like any device this old, Barnacks also exhibit many quirks that one must learn to overcome and/or embrace in order to find fulfillment in using them.

Loading

Loading a Barnack is probably the first challenge that new users face. Unlike the conventional hinged rear door that dominates single lens reflex and newer rangefinder camera design, Barnacks require that film not only be loaded from the bottom of the camera but that the leader of the film is trimmed to fit into a removable take-up spool.

Because 35mm film was originally just cut down motion picture stock, photographers had to load 36 exposures worth of a larger film reel it into canisters and trim the leader themselves. Modern, pre-packaged 35mm comes with a shorter leader than Barnack Leica’s were designed for and therefore they should be trimmed to these early specifications.

Next, you’ll begin removing parts of the camera! Take the bottom plate off the camera body then pull the take-up spool out of it.

Some folks remove the lens at this point also – in order to ensure a properly seated leader. Some photographers slip their business cards inside their Barnack to properly guide the film into place. Granted, none of this should be necessary if the film leader is properly trimmed but everyone’s got their own way of doing it!

Whatever method works best for you, plan on growing a third hand so that you don’t misplace the bottom of your camera, the reel, the lens, or the film!

Tiny View and Rangefinder Windows

Along with film loading, new users often find that the diminutive and separate view and rangefinder windows take some getting used to.

The original Leica I’s of the 1920s were simple viewfinder cameras without any built-in focusing aid. The entire body is not much larger than it needs to be in order to hold a 35mm film cassette. Oscar Barnack wanted to maintain this essential form factor when rangefinder focusing was added to the Leica II in 1932. With priority given to comfortably sized controls, the rangefinder assembly is perfectly flush with the tops of the advance and rewind knobs.

The view and rangefinder windows, though tiny, should be bright, clear, and easy to use effectively. And because the view and rangefinder windows are separated, instead of combined like on newer rangefinder cameras, the photographer is able to concentrate wholly on composition or on focus, one step at a time.

Adding an accessory viewfinder such as the 5cm brightline SBOOI is a popular way to make composing Barnack photos more enjoyable, though probably no more accurate!

To focus, one must align the tiny double image seen through the rangefinder window. In the 1930s this type of focusing was called “automatic” but today, it’s considered to be about as manual and basic a focusing device as one can find!

Knob-wind

Two prominent features of Barnack cameras are the knurled rewind and advance knobs that punctuate either side of the top plate. Most film photographers are accustomed to advancing their film after each photo by using a lever and rewinding at the end of the roll with a crank. While Barnacks pre-date these now-common features, they do boast double exposure prevention – another “automatic” innovation.

If you’ve ever shot a Holga or other simple medium format camera, you have probably wound the advance knob too far or not far enough which resulted in overlapping or fewer images. Barnacks do not allow this to happen. Turn the film advance knob until it comes to a hard stop. You’re at the next frame and the shutter is also charged.

These features seem basic now but remember, Barnacks were designed at a time when advance knobs just freely spun and shutter charging was done as another separate step.

Shutter Speed Dial

Because of its gearing, the shutter speed dial visibly rotates as one advances the film. Then, as a photo is taken, the dial rapidly spins back in the other direction, contributing a little “whoosh” to the whispery “clink” of the shutter release. This quirk is rather endearing and provides a front-row seat to the humble mechanical nature of the Barnack Leica.

Whimsical as it might be, it’s important not to touch the shutter speed dial while taking a photo, or the shutter timing will be interrupted. Also, one should be mindful to advance the film first and set the shutter speed second. Else, an unintended shutter speed will be selected. Some say that setting the speed before advancing can damage the camera but I have never found this to be the case.

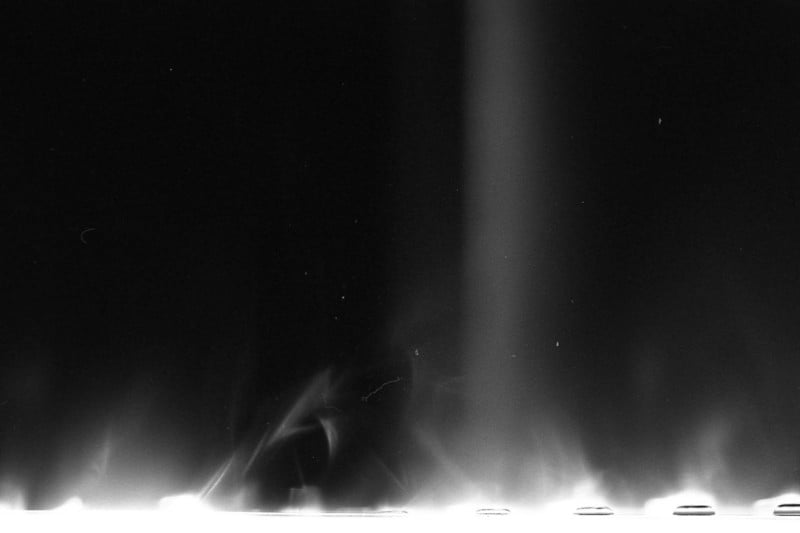

Light Leaks

Some say that Leicas are the best-built cameras in the world. But Barnacks can exhibit elusive light leaks since they were not designed with fast modern film in mind. It seems that leaking around the shutter curtains is fairly common as felt baffles age or fall away entirely. The cloth shutter curtains themselves can admit stray light if they are not perfectly adjusted and flat. Missing or loose body screws and areas where the vulcanite covering is chipped off can allow light to strike the film also.

Even ace Leica repair tech Youxin Ye told me “IIIc is not a very well-sealed camera. Leica improved the seal after IIIf. For light leaks, we can only do the best, no one can give you a guarantee on this. Bear in mind the age of the camera and technology in that era.”

Barnack photographers deal with these issues by ensuring that their camera has been recently and fully serviced by a qualified technician like Ye. And then we keep our cameras out of the sun for long periods when shooting 400 and faster speed film. It’s also wise to make a habit of keeping the lens covered between photos when possible.

Sunburn

Perhaps the most notorious quirk with Barnack Leica cameras, as well as any other cloth-shuttered rangefinder, is their proclivity to being damaged by direct sunlight. You see, unlike rangefinders with metal shutters or SLRs with a flipping mirror, once the lens cap is removed from a Barnack, sunlight can be magnified by the taking lens and literally burn a hole through its delicate cloth shutter curtain.

This can be prevented by keeping one’s lens covered or stopped down and pointed to the ground when not in use.

No wonder you don’t see a lot of sunrise photos taken with old Leicas!

Sprocket Holes

Another fun character trait of old Barnack Leicas are the appearance of sprocket holes within the bottom of the image frame.

Along with trimming the film leader, this is another vestige of the early days of photographer-rolled 35mm film.

Barnacks were designed to use a slightly taller film canister than modern disposable ones. When using the modern ones, the film can actually slip out of position, causing the sprocket holes to fall into the image plane. The images from some cameras are worse than others but the holes can simply be cropped out in editing if desired. On the IIIc and newer models, there is a small protrusion on the baseplate that keeps the film from falling out of alignment. Owners of earlier models will sometimes add a spacer to the inside of the baseplate where the film canister sits. The idea is to raise the film up high enough inside the camera so that the sprocket holes remain outside the image area. However, many photographers enjoy a signature of their format gracing their photos!

Flare and Glow

Most photographers alive today grew up with multi-coated camera lenses and have been blissfully unaware of how dramatic an effect this seemingly small innovation has had on our photographs. Most lenses made before the 1950s do not feature any anti-reflective UV coating or just a single, thin layer of it on the front element.

In addition, early lens glass was physically soft and scratched easily during cleaning. This left few well-used lenses unharmed. Lubricants used to facilitate the smooth movement of aperture blades evaporate and settle on the inner surfaces of old lenses. Balsam is a natural cement used to adhere optical elements together that can separate with age and exposure to heat.

By the late 1960s and particularly into the 1970s, multiple layers of anti-UV coating became standard and optical cements and lubricants were better suited for extended use.

So you might be surprised to see that early Leitz lenses that fit Barnack cameras tend to flare considerably and highlights feature an angelic glow. But contrast and apparent sharpness can be increased by getting these vintage lenses serviced. And then by using a correctly sized lens shade and contrast filter. A higher contrast film and developer help too.

Barnack photographers also become accustomed to using their lenses in such a way as to avoid excessive flare. If you’re after a modern look when using an old Barnack, you can also shoot with a 21st-century Cosina Voigtlander LTM lens that has multi-coating.

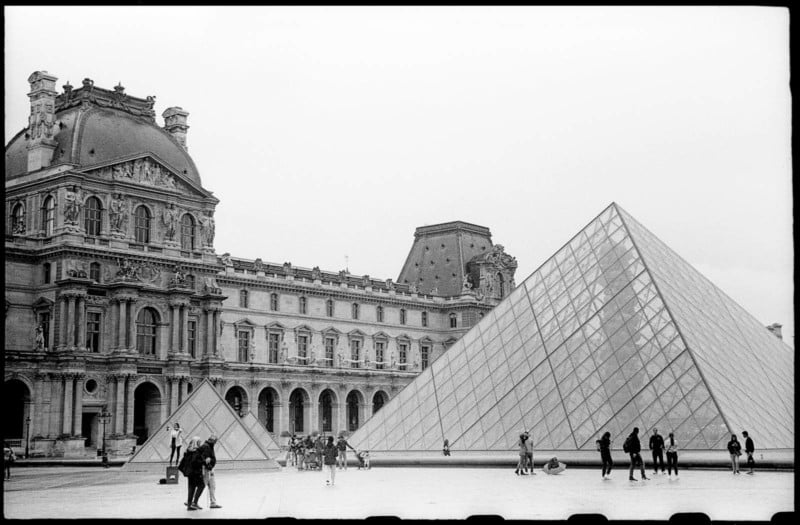

Once You Get Past All That…

At this point, you might be wondering why anyone would go to all this trouble to use a Barnack. And that’s the thing, if you see all this as trouble, yeah, this might not be a good camera for you. But if you see all these quirks as fun, well, you might really enjoy and get a lot out of using an old Barnack Leica.

They say that the camera doesn’t matter, only the photographer. But I think the camera has a little something to do with the results too.

Once you get the hang of it, a Barnack makes for an excellent conversation-starting daily carry, an artsy travel camera, or a family heirloom that unites generations.

An old Leica Barnack can also be a portal into a time when cameras and photographs themselves were unique, laboriously hand-crafted, tangible objects that both stopped time and transcended it.

Shooting a Barnack might just help you find something in your photography that you didn’t even realize was missing: more of yourself.

About the author: Johnny Martyr is an East Coast film photographer. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. After an adventurous 20-year photographic journey, he now shoots exclusively on B&W 35mm film that he painstakingly hand-processes and digitizes. Choosing to work with only a select few clients per annum, Martyr’s uncommonly personalized process ensures unsurpassed quality as well as stylish, natural & timeless imagery that will endure for decades. You can find more of his work on his website, Flickr, Facebook, and Instagram.

Image credits: Header photo © Kameraprojekt Graz 2015 / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0