A Long-Term Review of the iPhone 12 Camera

![]()

I use my phone like most people. I scroll through my social media feeds, order from overpriced delivery apps, and even make the occasional phone call. But in 2021, there’s one feature alone that decides how much I’ll spend on a phone: the camera.

The iPhone 12 launched four and a half months ago, to a flash flood of reviews. When you only have a week with a review unit, even with the best synthetic photography benchmarks, you end up with a first impression. Smart cameras call for real-world trials to understand their strengths and weaknesses.

Over the last four months, I’ve taken my iPhone to deserts and snow, mounted it on motorcycles, hiked into the wilderness, and gone swimming with it. I was left with a lot of photos and some interesting findings, and I’m excited to present a real-world review of the iPhone 12 lineup.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

iPhones 12

Fall 2020 saw four new iPhones with differences ranging in size, features, and finish:

![]()

I’m privileged to work on a camera app, as we have to acquire every variant of every iPhone model each year. This review will focus on the two extremes: the iPhone 12 Pro Max and its tiny cousin, the iPhone 12 mini.

It’s easy to fall into the mistake of grading and comparing an iPhone on its year-over-year improvements. Most people do not upgrade their phone every year. Similarly, it’s not great to benchmark an iPhone against a full-frame professional digital camera.

A 40+ megapixel, full-frame sensor camera will win against an iPhone in hardware-based image quality. That’s just physics. What the cameras in our phones are fighting for, however, is a total equation where good enough meets ease of use, flexibility, and portability.

If I’m going on a once-in-a-lifetime trip, I’ll carry along a big camera. If I’m getting married, I’ll hire a professional photographer with a big camera. But what about a weeklong vacation? Watching your children growing up? Practicing photography, and observing the ebbs and flows of everyday life? I find myself carrying cameras less, and shooting with my iPhone more.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

It’s a Hard(ware) Thing

Almost every modern camera refresh is one part evolutionary, and one part revolutionary. Hardware tends to evolve, with incremental sensor and lens improvements. Short of a surprise breakthrough in hardware, companies focus on revolutionary software to make the most of light gathered in sensors.

![]()

We dove into the hardware changes when the iPhone 12 launched, but it’s worth a quick recap.

The baseline iPhone 12 camera is truly a slight evolution. The main camera (we’ll call it ‘wide’) has a slightly larger aperture, moving from f1.8 to f1.6. That works out to 27% more light than the previous generation. Meanwhile, the Max-sized phone saw a larger evolutionary leap (so to speak) with a 47% larger sensor. Apple chose to not add megapixels on this bigger sensor, but pack in larger photo-sites, which makes for better low-light photography. Apple claims an 87% improvement in light collection, and it sure looks it.

This larger wide-angle camera includes a sensor-shift-based stabilization system. While other iPhones move the lens when stabilizing the shot, the 12 Pro Max moves the entire sensor assembly for better stabilization. It’s like the world’s tiniest gimbal.

The iPhone 12 Pro Max also received a 65mm equivalent telephoto lens, the longest lens ever put in an iPhone. This enables sharper shots of faraway subjects, but it’s a subtle improvement over last year’s 52mm. Prior “Pro” models ranged from 26mm to 52mm — you might know this as 1x to 2x — and the 12 Pro Max’s 26mm to 65mm equals 1x to 2.5x.

The presence of any sort of telephoto lens is the most obvious difference between the Pro and Non-Pro iPhones. If you have an on an older generation iPhone with a telephoto camera, and you’re tempted to downsize to an iPhone 12 Mini for the ergonomics, David Smith has a great check for whether you’ll miss it. Create a smart album in your Photos app, and quickly scan for images taken with the telephoto lens.

I’m trying out the XR, but was curious how much I’ll actually miss the telephoto lens.

I realized I can check using a smart album in Photos on the Mac. For me the telephoto was used in only 16% of my iPhone X photos. pic.twitter.com/N3YRjp4cFL

— David Smith (@_DavidSmith) October 29, 2018

It turns out about half of my photos on the iPhone 12 Pro and Pro Max are taken with that longer lens.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

I think it’s the telephoto lens— not the larger sensor, faster aperture, or even ProRAW— that makes the iPhone 12 Pro Max the photographer’s phone. You are forced to be creative; to choose what’s in the shot. You can make a background loom dramatically, capture flattering portraits, and take some distance from your subjects. The Max’s telephoto camera is now blessed with a sensor that has quite a nice output and even supports ProRAW.

Manual focus with the telephoto lens makes it even more fun, with its beautiful, ‘natural’ bokeh. There’s even more of it now with the slightly larger aperture. (You need an app like Halide to use manual focus)

Sadly, the telephoto camera remains the only camera on your iPhone that doesn’t support Night Mode. These beefy new iPhones still just crop part of your Wide camera image and pass that off as a capture from your telephoto lens. Even the Ultra-wide lens now supports Night Mode. I really hope we’ll see this done ‘properly’ in the next iPhone.

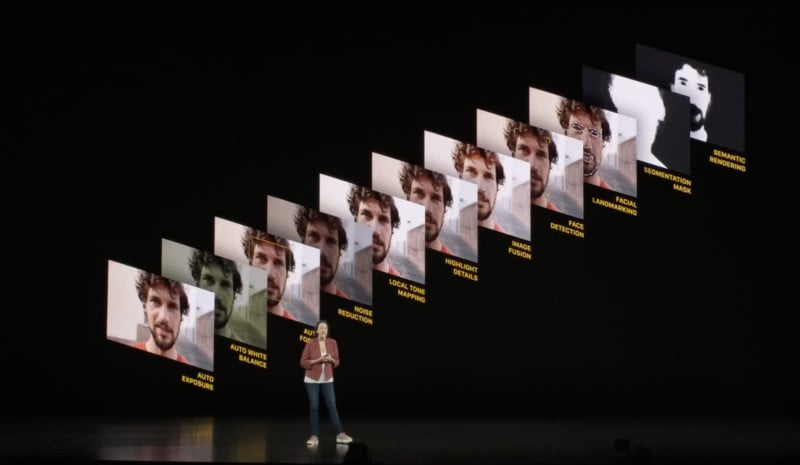

The Pipeline

If there’s any hardware revision to be excited about year over year, it’s not the camera, but the processor and memory of your new iPhone. Apple makes the fastest mobile chips hands-down, which unlock new tricks to create images previously impossible in sensors the size of your thumbnail.

Apple now actively markets their smart photography pipeline. They give brand names to algorithms, like Smart HDR and Deep Fusion. These complex technologies use all the power of the latest chipsets, such as real-time machine learning that selectively enhance details in areas, guesses white balance in night shots, detects subjects, and more. It’s no exaggeration to say that the iPhone 12 is the smartest camera Apple has built yet. Does it result in a better shot?

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

For casual photography, yes. Earlier generations (cough, iPhone XS) struggled to retain detail after aggressive ‘smart’ noise reduction. Apple’s new smart technologies generate much more natural images. Whether it’s people or animals, detail is retained in skin and hair.

Contrast this with the many Android phones that enable problematic effects like skin-smoothing, by default. Making automatic ‘enhancement’ of your image opt-out sets a scary precedent.

Will future phones make you skinnier, and give you bigger eyes? Our ideals of beauty matter, and while photography is subjective, an automatic ‘lens’ on the most-used cameras of our time will greatly affect society and those in it, especially impressionable young humans. I have no doubt that Apple considered ‘beautifying’ effects to remain competitive, but I’m happy to see them remain absent.

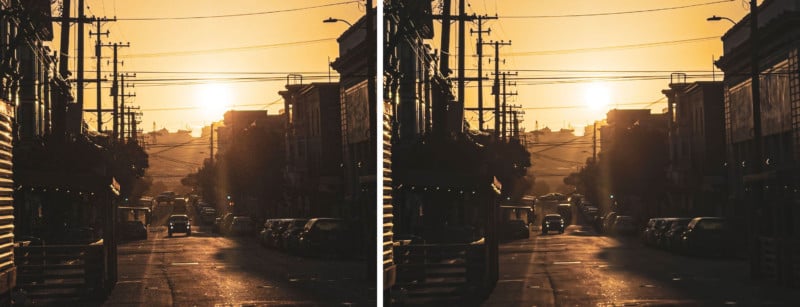

While the iPhone does a lot of processing, it’s conservative in its… editorial decisions. It’s not afraid to let you take a bad photo: color saturation and contrast are fairly neutral, with its white balance skewing towards taking warmer images. I don’t mind that: I think that’s a ‘look’ that we’ve come to expect from Apple.

The only time that I found the smart image processing on the iPhone noticeably bothersome is when skies get overly tinted blue. It’s clear that the iPhone can now easily detect and segment the sky in a shot, and it applies nice smooth noise reduction to it to get wonderful gradients. But even cloudy skies tend to get a blue cast that isn’t as neutral as you’d like.

Meanwhile, some Android phones make such aggressive changes that they’re accused of adding a fake moon.

Low Light

iPhone 12 collects more light, so it takes nice photos when the sun starts to set. I found that I got a lot less noise in my RAW files and more detail in my non-RAW files quite consistently. Once the sun goes below the horizon, the camera app can also manage to take photos without Night mode. The benefit to this is more detail (less noise reduction), and the ability to take low-light Live Photos.

It’s not really news that the iPhone 12 is the best low-light camera Apple has built yet. With the introduction of Night mode, Apple brought a very robust computational-photography-based long exposure option to the masses (I love a good computational long exposure tool).

You’ll find that you can take Night mode shots on the new iPhones in surprisingly dark conditions. Coming from an iPhone that lacked night mode can be kind of mind-blowing, and even larger digital cameras will feel some envy seeing an iPhone do hand-held ’10 second exposures’.

I add quotes there because while Apple gives you a nice duration setting, it always attempts to get a sharp shot. Night Mode is a classic Apple solution: ease of use through no real configurability. Getting light trails or soft effects is impossible, as it prioritizes getting a ‘sharp frame’ and then stacking additional detail onto it.

You can, however, let the iPhone get steady enough on a surface (hey, the sides are flat now) or on a tripod to select an exposure time of up to 30 seconds.

In a pitch-black night moonless night in New Mexico, that can get some really impressive shots:

Here are 10, 15, and 30-second exposures with an iPhone 12 Pro on Night Mode. This is impressive!

Now, does this stack up against a larger camera yet? I wouldn’t say so. What is harming Night Mode the most for serious photography is its inflexibility. Support for ProRAW helps a lot — that adds more detail and adjustability to the heavily processed output.

But as developers of a camera app, we’d love to have a Night Mode API to add options like how much frame blending is done, what level of noise reduction is applied, and more. Doing a ‘true’ long exposure like this:

Is just not possible right now as the iPhone will optimize to get those cars sharp. That makes perfect sense: Night Mode is optimized for most people, who will likely take photos of friends in a dim restaurant, or the moon over the city. You want sharp shots. But as always, taking away options to make a feature accessible and easy to use also comes at an expense of utility to those that are pursuing creative options beyond what the camera prescribes.

Let’s hope for a Night Mode API in the future.

LIDAR and You

iPhone 12 Pro has a particularly interesting looking shape on its camera mesa which does not protrude, unlike its camera lenses. Underneath this opaque reflective disk lives a sensor that does something very cool. It senses depth.

![]()

The LIDAR sensor debuted in the 2020 iPad Pro. Under that disc on the iPhone 12 Pro lives a similar, but slightly smaller unit. These sensors work by emitting light in a pattern of dots and measuring the time it takes for a photon from these dots to reflect off a surface and travel back to the sensor. You’ll also see these sensors referred to as ‘Time-of-Flight’ sensors for this reason, and it’s not just you — this is absolutely mind-blowing technology. Light travels very fast: these sensors are kind of a miracle.

In operation, it looks something like this (the LIDAR sensor projects a fairly wide-spaced dot pattern that covers your subject):

And if you were to be on the receiving end, something like this (what ‘you’ see when you are being blasted with the LIDAR):

The pattern of dots exactly fits the coverage of the iPhone’s ‘wide’ camera, to speed up autofocus. This is very useful in low light, when autofocus scans for whether your subject is close or far away. Normally, a camera looks for sharp edges to figure out focus, which is difficult in low light. With LIDAR, it instantly senses the subject’s distance, allowing you to shoot right away.

This is similar to how the Face ID (or ‘TrueDepth’) sensor housed the iPhone “notch” works. Here’s FaceID in action, shot in infrared:

Unlike FaceID, LIDAR fires its ‘dots’ once per second when in regular camera modes, and even when recording video. In portrait mode, it fires much faster. The intensity of the projected light is quite intense; in the above video, the LIDAR dots are about as intense on the subject as a car headlight. This is likely so it works in daylight.

You can test LIDAR’s efficacy easily: just cover it with your finger. You’ll notice it doesn’t make a huge difference in daytime. At times, it’s even a hindrance, as the LIDAR beams reflect and scatter off transparent surfaces. Shooting out of an airplane window or through a sliding glass door sometimes makes your iPhone slow to focus, as it confuses transparent surfaces with opaque ones. When that happens, just cover the dot with your finger, and your iPhone will fall back to conventional focus based on edges in the image.

The iPhone 12 Pro’s LIDAR sensor is designed to map things at a large scale, and in motion. This is very evident with the prototype app we built for the iPad Pro: when moved, the LIDAR sensor will work to map a sort of 3D mesh of its environment. With some machine learning and data from the cameras, it can turn this into a fairly crude 3D model of say, a room. It can map features like tables, doorways, and windows OK. It’s far too crude for say, 3D scanning smaller objects, though.

LIDAR-Powered Portrait Mode

In Apple’s announcement event, the LIDAR feature was hailed as something usable for a new dual-mode computational trick: Portrait mode Night mode — or Night mode Portrait mode, if you prefer. (Apple officially calls it ‘Night mode Portrait’)

![]()

Night mode combines several images to get a crisp shot in low light; Portrait mode uses multiple cameras to create a depth map that can let the iPhone assess its distance from various regions in the image to create a somewhat convincing shallow depth of field effect. There are two significant challenges for the camera here: determining what is in focus and generating a good map of depth in the shot.

I am perhaps unique in that I barely ever use Portrait mode. I just don’t find myself enjoying it. Too frequently, the effect of Portrait mode is still too artificial-looking, and I’m not a huge fan of the camera restricting it when I am too close or far from my subject.

For the sake of this review, I tested the latest Portrait mode on a few shoots and got a few shots that I was happy with:

![]()

![]()

How does it stack up? It’s still not as nice as a ‘proper’ camera, but far more flexible than having to tote around a big camera and lens for a similar shot:

![]()

Portrait mode doesn’t seem very optimized for shooting objects that aren’t people or pets, so you’ll find that it occasionally just doesn’t blur parts of the scene. That makes it challenging to use for creative setups like the shot above, where it will simply not blur the foreground.

It stacks up great against other phones, though: Even without LIDAR, Portrait mode on the iPhone 12 mini is significantly better than previous generation iPhones. If you are coming from an iPhone XS or X, it’s a major leap. The ability to adjust depth (in real-time or after the shot) is great, and Portrait Lighting creates more flattering portraits even in bad light.

In the past, the Portrait AI would improperly mask parts of your image, leaving segments of your image sharp or blurry when they shouldn’t. This jarring mistake seems much rarer.

Initially, I hadn’t tested Portrait + Night mode very much. In the few tests I did, though — comparing it to a regular camera and the iPhone 12 mini, which is unequipped with a LIDAR sensor, it works outrageously well:

This is also a testament to the utter computational magic on display here.

The image on the right was taken on Sony’s latest and greatest full-frame camera, the A1. At wide-open (1.4) aperture, ISO 12800 and 1/15th of a second, it captured a decently usable shot in this very dark setting. That an iPhone can take a photo like that here is nothing short of incredible. LIDAR comes in clutch.

I can hear you wonder: “does this really use LIDAR that much?” and the answer, as tested with an infrared camera, is yes:

In very low light, the Night mode Portrait feature actually goes from rapid blinking to ‘holding’ the LIDAR projection for a moment at higher brightness to ensure it gets sharp frames and, presumably, a better depth map. I would imagine detecting depth with the two cameras is much harder when there isn’t enough light to really see any parallax.

So yes, LIDAR is definitely nice to have in this camera. In addition to being a better night-time portrait taker, the autofocus is actually quite fantastic if you’re shooting some action-y scenes. ProRAW or not, the iPhone doesn’t really take fast RAW shots, so getting sharp focus or action in focus is essential. The LIDAR sensor makes short work of focus when opening the camera to get a shot.

ProRAW

On that note, let’s talk about Apple ProRAW.

ProRAW came out a little after the iPhone 12 Pro Max and Mini hit the market. At Lux, we were quite excited when ProRAW came out, despite some worries from folks that we would be threatened in some form because the stock camera app would be getting some type of RAW capture.

A rising tide lifts all boats! Apple introducing a special1 RAW format for the iPhone camera means a commitment to RAW shooting, and the more people know about RAW, the more people might be interested in a better camera for iPhone.

We’ve previously written a lot about ProRAW — so if you want an explainer about RAW and how it works, and how ProRAW is unique I recommend reading that, followed by Austin Mann’s excellent article on it.

I will just touch on ProRAW and its capture experience here.

ProRAW is a powerful new tool in the iPhone photographer’s tool chest because it brings some of the ‘smarts’ of the iPhone camera pipeline to the flexible RAW format.

Smarts? Essentially, your iPhone takes many shots in rapid succession and intelligently blends them to fuse together a great shot. Some shots are under- and overexposed, to get more detail in the shadows and recover highlights. iOS also uses machine learning to identify areas that should get more or less noise reduction, to retain the most detail.

One of the most mind-blowing examples of the ‘smart’ photography in the iPhone camera is that you’ve probably never actually taken a photo on your iPhone. The iPhone has done it for you.

The camera is essentially always taking photos when it is open, keeping a rolling buffer of shots. When you tap the shutter button, it can go back and grab a frame from right *before* you pressed the screen, giving the impression of a zero-shutter-lag camera. What’s more, because of the rolling buffer, it can quickly check several shots and choose the least shaky one when you’re moving to ensure you got the best shot.

To some, this feels a bit… wrong. You can’t quite place your finger on it, but it starts to enter an uncanny valley of sorts. At what point do you lose agency as a photographer? Is it you, or the camera that is calling the shots and making the creative choices?

Enter RAW. RAW files are often loved by photographers because they’re also (often) lossless and give you far more data than the typical output format of your camera (JPG or HEIC) which enables enormous freedom when editing your shot later.

But on iPhone, I really came to love RAW because it skips (almost) all of the processing and just gives you the image as it is. With RAW on iPhone, you take the photo, and there is no recombination of frames happening to get you a different result.

On iPhone XS, this was immensely beneficial — noise reduction on these cameras was aggressive and could really remove some detail. Since then, iPhone sensors have gotten bigger and better, which means less noise. But processing also increased, as cameras got smarter each year.

This year, RAW got smarter. ProRAW brings that advanced image pipeline — the merging of frames, selective detail enhancement, and more — to a virtually lossless, scene-referred format.

ProRAW output is excellent. While the ‘regular’ RAW files out of the iPhone 12 cameras are already excellent, with far lower noise than seen in previous cameras and tons of detail, the benefits of ProRAW shine when shooting in tricky conditions when available light would introduce a lot of noise to your shot, or when merged frames can give lots of extra dynamic range.

I don’t seem to be alone: in some quick polling on our Twitter, we found that most iPhone 12 Pro users opt for it, despite it being much slower to capture.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Only iPhone 12 Pro and Pro Max get ProRAW, and not only because they have ‘Pro’ in the name. They have much more RAM than their unprofessional, less RAW-savvy siblings.

Note: It has to be mentioned that with an app like Halide, you can still shoot RAW on the non-Pro iPhone 12 and 12 mini to great effect — but even we developers cannot bring ProRAW to these phones.

ProRAW doesn’t end there: it brings RAW to modes and even cameras that do not normally support any type of RAW capture. The ultra-wide camera gets RAW, and so does Night mode.

ProRAW is an excellent tool to add to the iPhone camera, but like Night mode, it is somewhat lacking in flexibility. It can be aggressive in noise reduction, particularly when using a process like Deep Fusion which merges many frames to get a good result.

The Gripes

That’s all a very positive overall impression of the iPhone 12 series, but what remains a legitimate photographic issue on these phones?

Apart from inflexibility in the images you can capture — which is largely negated by apps like Halide that give you extra control — the iPhone suffers from a few camera issues that will probably be solved with upgraded hardware in the future.

Flaring on the ultra-wide and wide cameras is not just noticeable, but outright bothersome when shooting into light. In the above image, you can see the telltale iPhone ‘green orb’ flare that is a result of internal reflections in the lens. This can be fairly unobtrusive as in that shot, but when shooting many bright point sources of light head-on, can outright ruin a shot.

I will give this to Apple: It’s very, very challenging to eliminate this in optics, but it’s still a nuisance when shooting on an iPhone.

Then there’s noise reduction.

Noise reduction is something I never really enjoyed on iPhones, and I find it really bothersome that ProRAW does not give granular control over how much is applied to a final image. When shooting in dark conditions with the iPhone’s less light-sensitive cameras, you can get muddled images that would’ve looked nicer with some grain. It’s almost like a watercolor painting:

This looks fine at first glance, but even slightly zoomed in:

![]()

Ouch. I would’ve probably preferred the noise. Unfortunately there’s no way to see what that would’ve looked like, as native RAW is simply not available on the ultra-wide camera.

Conclusion

iPhone 12 is, at its core, a showcase of how much software really matters in cameras nowadays.

Five years ago, we would have likely looked at the camera improvements on the iPhone 12 by focusing on what is new under that camera bump. While an improvement in the lens is nice, we would’ve probably shrugged it off as a minor improvement. Evolution.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Apple did something smarter than trying to do the impossible with the limited space they had in the physical world: they spent a cycle refining, redesigning, and hugely investing in the software that gets more out of the cameras. What they achieved is truly impressive. But what I find equally impressive is the pitfall they avoided.

One of my dearest friends is a type designer. That means he designs typefaces for all sorts of things: he created the custom typeface we use in Halide, for instance. But he once had a job creating a family of typefaces for the local newspaper.

I asked him what truly defined success in the design of a typeface like that, and he just smiled at me and said, “when people don’t notice the typeface at all.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

Smart image processing, magical multi-frame combination, deep fusion, night mode: the best camera is the one that is not just on you, but gets out of the way. That takes a great photo, yet does this smart enough to make you feel like you actually took it. A camera that takes better photos but remains neutral — allowing the photographer the flexibility to edit it afterward to make it fit their mood and artistic vision.

Great cameras let you fail.

Apple largely succeeded in doing that. I have no doubt that the temptation for their camera team is immense: they have the most powerful chips in the industry, the greatest freedom to create a camera that can simply do no wrong: that can over-process any image to look good to most people.

Yet, the iPhone remains truthful. It’s a true tool for photographers while democratizing photography for a vast population with technologies that make challenging conditions easier to shoot in. It processes your images more, takes better photos for every user, and even offers substantial options for the pros — without sacrificing authenticity.

It’s a photographer’s phone. And it’s a great camera.

1 Based on open standards: ProRAW shoots into a regular DNG format, which is fantastic.

About the author: Sebastiaan de With is the co-founder and developer of Halide, a groundbreaking iPhone camera app for deliberate and thoughtful photography. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can connect with him on Twitter. This article was also published here.