Film is Alive!… But it May Have a Terminal Illness

![]()

The defiant cry of the nostalgic hipster that’s become a hashtag: #filmisnotdead. But why? It’s 2019, people — the digital camera reigns supreme; why won’t this analog trend die? Rationalism abandons the old way in recognition of the new’s superior efficiency. The combine harvester supplanted the scythe, clocks replaced the sundial, and electric lights extinguished the candle.

Kendell Jenner wears a Contax T2 on The Tonight Show and suddenly every teen girl and her dog wants a film camera. But I’m not a sociologist — I am a photographer and a lab operator, and I have a few insights into why film has risen from the deathbed and another reason why it might very soon go back to it.

Why Film is Still Kicking

Ever since I started photography, I have always had the luxury of choosing either film or digital. In fact, I had two cameras when I first started: a Nikon D40 and a Pentax ME. Both were serviceable, and being that I only shot amateurish street photography, landscapes, and portraits, both cameras did essentially the same thing.

Most of the time I shot at shutter speeds less than 1/1000s and with ISOs rarely higher than 1600. Arguably, the Pentax did a better job, using a 50mm f/1.8 prime lens compared to the plastic-fantastic kit 18-55mm on the D40, and it offering full frame resolution with a quality scan.

Yes, I could take more photos with my D40, but that did not guarantee better shots. In fact, I would generally waste them, receiving the instant gratification of the LCD compared to the slow contemplation and cost associated with C-41.

Comparing image quality, a middle of the road digital camera and basic film scans offer roughly the same resolution. I rarely ever print over 12×18-inches large anyway, so the difference is academic. And provided I have used the right film and exposed properly, I can get a decent print up to A1 size without too much grain.

Quality wise, there is not a vast difference between digital and film for most everyday applications other than the ability to review images instantaneously. The greatest advances in digital photography — faster and more accurate autofocus, low light performance, internal stabilization — generally only make great breakthroughs in areas outside of the everyday experience of photography, like astrophotography, sports, news journalism, and professional shooting.

The processing and storage of digital are both unlimited and far easier; but what if you only shoot a few hundred pictures a year? Is this so important? In focusing on the professional demand, we neglect the importance of the consumer market.

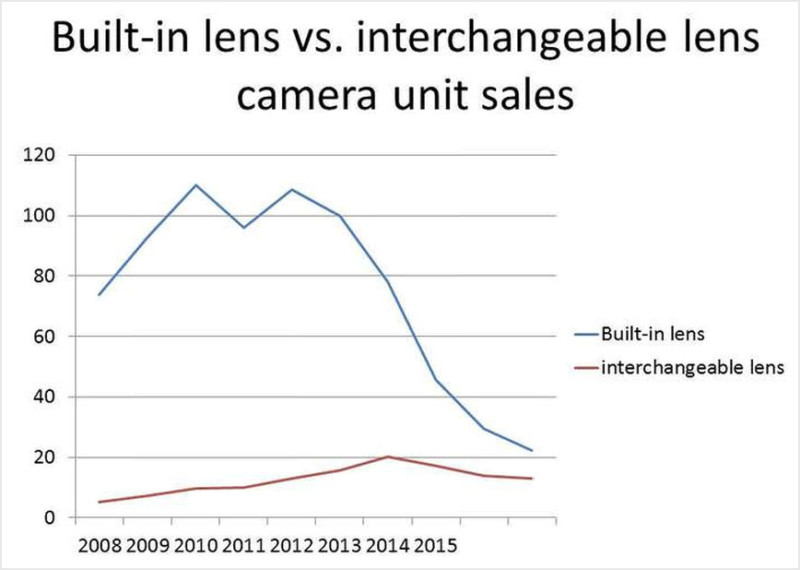

The consumer digital market has hit its peak and is rapidly decreasing; pros want the latest and greatest digicam, phones have all but replaced the compact camera.

It seems that the consumer just wants something light, cheap and unobtrusive to take happy snaps, which leaves either their phone or a nice, simple point-and-shoot film camera for special occasions.

During my time working in the minilab (2016 to 2018), I saw a huge uptick in the number of young people bringing in 35mm rolls or disposable cameras. We went from developing around 20 rolls a day to 80+ at a time when even more competing labs were opening. The majority of our sales were to the under-25 crowd, whose interest in film was because it did what it needed to do and not much more.

It is practical to them, but also fun with its inherent mysteries and spontaneity. A recent report can testify to my own anecdotal experience: “About a third of new film shooters are younger than 35, and roughly 60% of film users say they started shooting film in the last five years.”

The rise in popularity is evident in the increasing cost of film cameras, that has gotten so ridiculous that heavily used second hand mjus sell more than what they did when they were new.

![]()

Technological advances outside of photographics have altered the way people share photos. In this regard, digital photos from a camera can be more time consuming and arduous to share for the amateur shooter- requiring the pictures be imported to their computer, edited and then moved back into their phone to be shared.

At my lab, Dropbox changed the game for us. People found new convenience in the scans being emailed directly to them, with the pictures available straight on the camera roll, ‘filter’ preapplied. All it needs is a #filmisnotdead hashtag and it’s Insta-ready. Film processing is costly, but it’s also like outsourcing the file management of digital so you can concentrate on the photography part of photography.

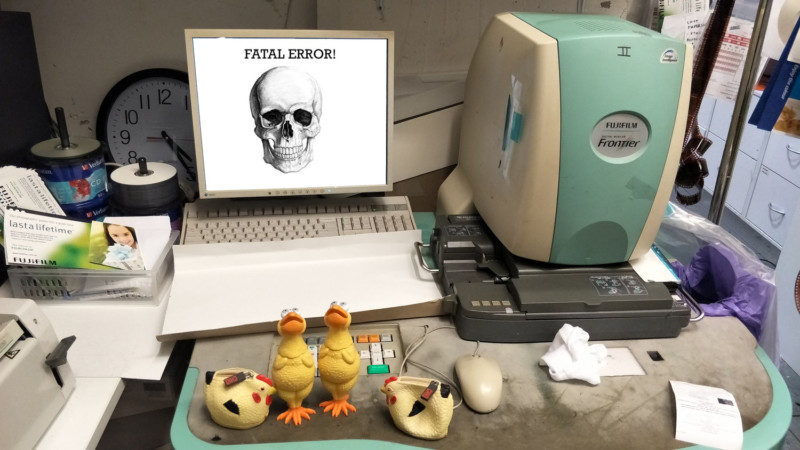

So the niche seems to be deeply carved out for film photography and the manufacturers, at least in the short-to-mid term. The real prognosis for analog is ironically tethered to the lifespan of certain digital cameras: the minilab scanner, which is slowly going extinct.

Why Film’s Death Clock is Ticking

Professional minilab scanners are key to film’s continued survival. Yes, you can scan with any digital camera or flatbed just as well as a dedicated film scanner, provided you know what you’re doing and build a good mask to hold the film flat. But the efficiency of a scanner like the FP-3000 is unrivaled, and essential for a lab to remain profitable.

Fuji has long discontinued production of these machines, and their assembling plants have long been shut down. Parts are available, but get fewer and more expensive every year, and most of these are being stripped off old, dead machines. When the motherboard or power supply goes, that machine is ready for the scrap heap, because these parts are no longer in production either.

I don’t know what it’s like for Noritsu labs, but I have a feeling it’s a similar story. Without professional film processing, there’s not really much appeal to film at all, and processing at large volume depends on dedicated film scanners. Unless someone starts making new scanning machines that can be both as efficient and deliver similar image quality, the long-term future of film looks bleak.

About the author: James Cater is a digital and analog photographer, film lab operator, and model. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can find more of Cater’s work on his website and Instagram. This article was also published here.