Interview: Conversation with Tintype Artist Keliy Anderson-Staley

Keliy Anderson-Staley is an assistant professor of photography at the University of Houston. Her work has been exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian, the California Museum of Photography and the Portland Museum of Art, and is currently on view at the Houston Center for Photography.

Her book of portraits, On a Wet Bough, is forthcoming from Waltz Books. She is represented by Catherine Edelman Gallery.

PetaPixel: First off, Keliy, talk about the influences — either current or from the past — who have really helped to shape your work.

Keliy Anderson-Staley: There are many photographers whose work I love, but my most direct influences come from the world of portraiture.

One is Mike Disfarmer, who I started looking at a lot when I was living in Arkansas (where he worked as a small town portrait photographer in the 30s, 40s and 50s). His studio practice was a little rough around the edges, but he had a distinctive style that transcended his practice as a local portrait photographer. I am particularly struck by his emphasis on the ordinary, on the plain, on the slightly odd.

Portraiture struggles sometimes to be taken seriously as an art form, so the artists who really elevate it to that status are ones I really admire: Felix Nadar, Julia Margaret Cameron, Malik Sadibe, Dawoud Bey, Diane Arbus, Carrie Mae Weems and Thomas Ruff.

PP: You’re well-known for your tintype photographs. Why decide to work with such an antiquated process? Why use tintype specifically, rather than, say, the daguerreotype or calotype processes?

K.A-S: When I made my first tintypes more than ten years ago, I had already been working with other historic processes. In college I had also experimented with Liquid Light (a paint-on silver emulsion) to print images onto baking pans, so I was always interested in thinking about the photograph as something other than just an image on paper. I was predisposed to fall in love with this process — with its messiness, with the hands-on nature of the process, with its implicit history.

I’ve tried daguerreotype. It’s a laborious and dangerous process, and I don’t love the resulting mirrored surface — they are hard images to see except from certain angles. Tintypes, on the other hand, have a real solid presence on the wall, and the eyes stare out at you.

I do love other historic printing processes, especially cyanotype and Van Dyke brown. I’ve used them for specific projects, but I keep coming back to the collodion process, especially to make portraits.

PP: I saw those baking pan images on your website, and they’re unusual, compelling, and fascinating pictures. What was the idea behind them?

K.A-S: The pans were part of my thesis project as an undergraduate student at Hampshire College. The project is titled an “Incomplete Family History.” I was working with the baking pans because of their connection to domestic life, family and my identity as a woman. They were all rusted (I collected them over several months at junkyards and thrift stores), so I was able to evoke ideas of time, decay, and the fading of memory.

The images were family pictures from my mother’s albums that I re-photographed on black and white film and exposed onto the pans using liquid silver emulsion. The pans are meant to be installed in a grid, with one pan almost completely rusted through. This pan represented my biological father who I had never met.

On a personal note, I just recently connected with him, and will be making a tintype portrait of him when I meet him for the first time this summer, so this project has come full circle.

PP: What is it about you, or your outlook on the world, that draws you to working with alternative processes in the first place? Especially now in this digital age when there are endless amounts of ways to make photographs? Does this preference for antiquated processes carry over anywhere else in your life?

K.A-S: Well, I’m not an old-fashioned person, and I didn’t start working with this process because I have any aversion to modern photography or digital processes. I am really interested in photographic history, though, and this process has been a way for me to engage with that history conceptually.

I like photography from every era, and there is a lot of great work being done digitally. For me, I think the key is to find the process that works best for what you want to say visually. I also grew up off the grid in a log cabin in northern Maine, without electricity or plumbing, so I am used to doing things the hard way.

PP: Can you tell us about the history of the tintype process, along with the ‘why’ and ‘how’ it was developed and utilized?

K.A-S: The wet-plate collodion process was invented in 1851 by Frederick Scott Archer. The daguerreotype had been invented in 1839. The first collodion images were on glass, but the tintype was invented shortly after (1853), and there is some debate about whether it was an American or a Frenchman who first used a metal (iron) plate.

In terms of the spread of photography as a mainstream medium, tintypes were crucial. They were cheaper than daguerreotypes and less vulnerable to damage than ambrotypes and glass negatives. Photographers set up studios all across the country. People were fascinated by photography and a lot of people thought they should have at least one photo portrait. Even children who died were photographed in postmortem tintypes.

The ubiquity of the process in that period is revealed by the fact that you can find piles of tintypes for sale at nearly any antique shop in the country today.

PP: We live in an era that’s saturated with a vast multitude of image-making methods, from different film and digital technologies, and with all the variations and modifications that come with them. How does it affect us psychologically when we see an image that looks like it was made over a hundred years ago, even if it was made yesterday?

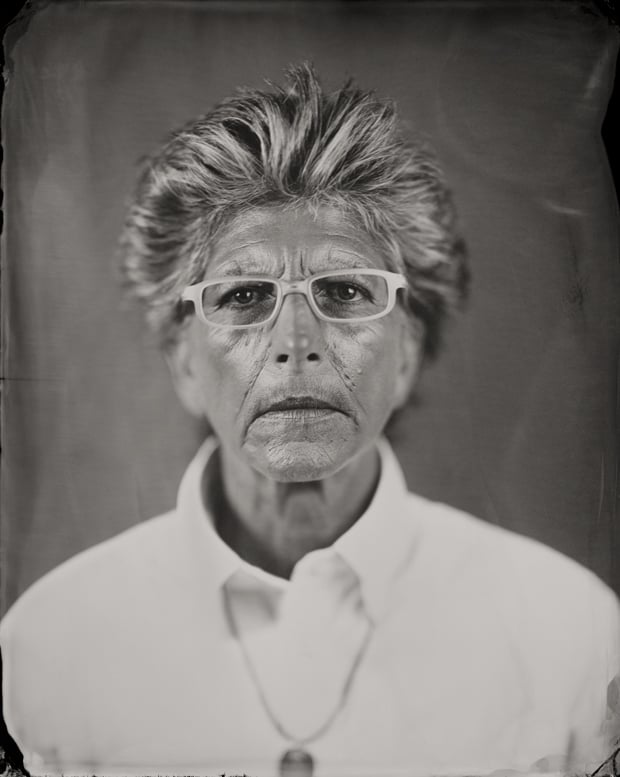

K.A-S: Not only is every photographic process ever invented still currently in use, but portraiture, in particular, is everywhere. Because of this saturation, I think it is pretty rare that we pause to really look at a face and examine it, the way we might standing in front of a portrait by Vermeer or Eakins.

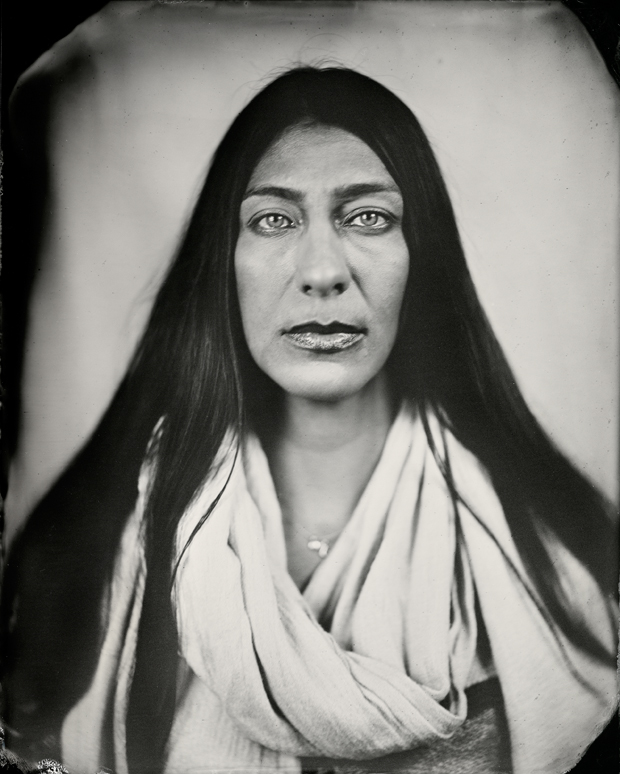

On some level I think just the seeming antiquity of the tintype image can be jarring. Even the people sitting for the image are frequently surprised by it — they recognize themselves, but also often say they see their grandparents.

The tintype, because it is a positive image, creates a mirror image, so the sitter is seeing himself or herself as they look in the mirror — this is truer to how they know their own face than any other photograph they’ve seen of it. The anachronistic nature of the contemporary tintype forces us to look more intently, to receive it as a portrait, something formal and special.

PP: Let’s talk about your portraits. Who are the people you photograph? What are you looking to draw out of them, and how do you hope viewers connect with your finished pieces?

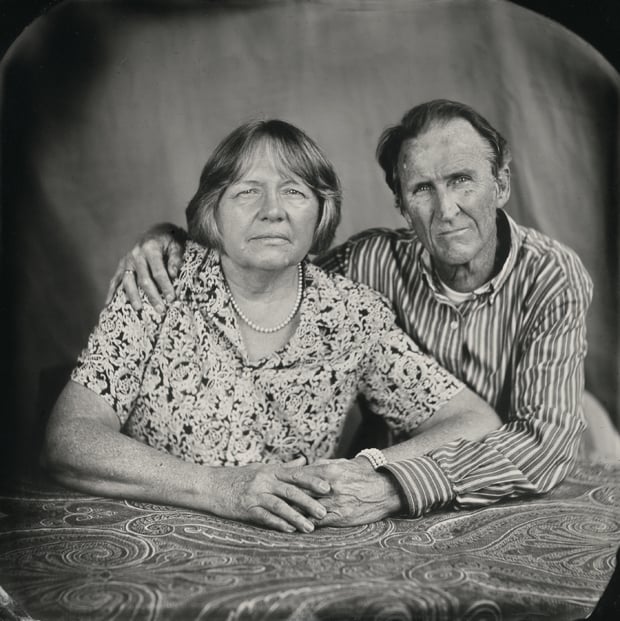

K.A-S: I photograph anyone and everyone, and I’ve photographed at universities and art institutions all over the country (the California Museum of Photography, the Southeast Museum of Photography in Florida, the Print Center in Philadelphia, Light Work in Syracuse, Morris Museum of Art in Augusta, Georgia, the Houston Center for Photography, a studio I had for years in Queens, the Art Expo on the Navy Pier in Chicago.) I’ve photographed at least 1500 people in wet plate since 2004, and I’m really grateful for all the people who have participated in my project.

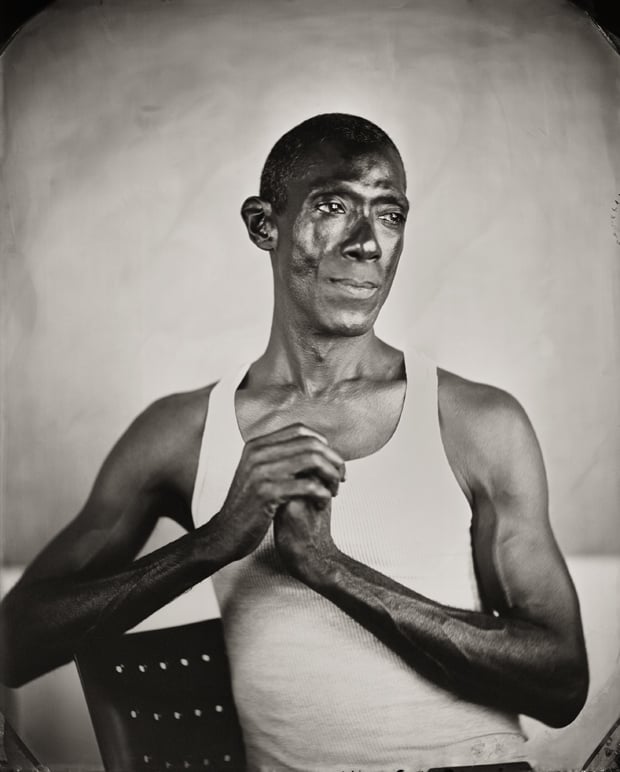

Collodion is an immediate process, like digital or Polaroid, but the image itself captures more than a single instant. The exposures are multiple seconds long, and this duration gives the subjects of the portrait a greater presence — at least I think I see something more present in the portraits. The eyes in each of these portraits stare out intently at the viewer. There is this kind of defiance in each face, a demand to be seen, a challenge to stare back.

In this sense, each person is given a something like a voice, even when they are in a crowd of tintypes, hung salon style as I often show them in my exhibitions. In this way, I hope my images challenge the non-democratic uses of this process in the nineteenth century (the ethnographic studies, typological racial portraits, and the exoticization of others).

PP: For you, is there a secret to making a compelling portrait? Or is it just experience? Or persistence?

K.A-S: A good portrait makes us want to look at a stranger. We can’t really know a person through an image, but a strong portrait should tell us something about them, make us feel that we know them in some way. My portraits are odd, though, in the sense that they don’t always look like the person, in that features may be distorted or blemishes exaggerated, and they can look “off” in some way, even when they are beautiful.

Ideally, in the studio, I will take several photographs of someone before I am sure I have one I want (this process only lets me make a few over the course of a couple hours — the plate needs to be coated in collodion, sensitized for three minutes in silver nitrate and then developed and fixed before I can move on to the next image). I am often set up in places where people come through quickly and are waiting for a turn, and I only have one chance to make an image of them.

In these cases, experience is crucial. The exposure time needs to be estimated, and it changes with the sun, of course, if we are outside, but different skin tones and hair require different exposure times, and one plate can vary from the next by seconds. So, I need to know what I want, how I want the person to pose, and to be sure to get it on the first try.

There is a degree of persistence, too. It can take a lot of effort to make sure everything comes together just right. Even with years of experience, things go wrong with the chemistry or equipment, and it can be a struggle sometimes to troubleshoot the problem. But that is part of why I love this process. When everything comes together and I get a great portrait, I have a surge of adrenalin and just keep shooting.

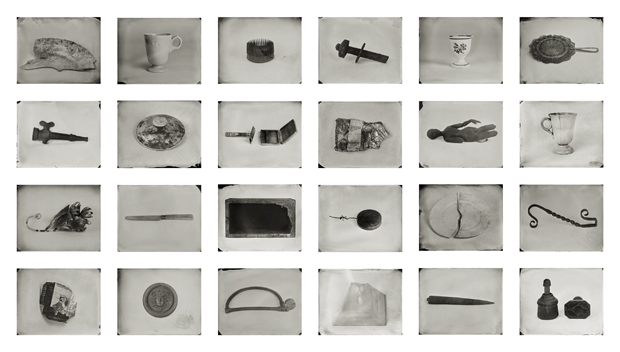

PP: You’ve also made still-life tintypes in a series called ‘The Winslow Homer’s Studio Project.’ Give us a brief introduction to Winslow Homer, and how did you come to photograph the objects in his studio? What was your goal?

K.A-S: This was a project I did on commission for the Portland Museum of Art in Maine, where the painter Winslow Homer lived and had his studio.

Homer was one of the more important nineteenth-century painters. Like Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner, who photographed the Civil War in tintype, Homer documented the war, but he was sending back drawings from the frontlines. The Portland Museum renovated Homer’s studio in Prouts Neck, Maine, and had a retrospective of his work in 2012. They commissioned several photographers working in 19th-century processes to photograph his studio and the ocean view he made so famous in some of his iconic seascapes.

I made some landscape tintypes, but I also thought it would be really interesting to photograph some of the objects they had found in the studio while renovating it (Homer used it as a home and workspace). I photographed the objects as I photograph people — each is a kind of portrait with a shallow focal plane and the subject isolated against the backdrop.

Many of them are quite mundane, though — crumpled cigarette packs, broken plates. There is also a chance none of it actually belonged to Homer — including the artist’s mannequin I photographed — because his family lived in the house for decades after his death.

I was really interested in this ambiguity. The museum had elevated these objects to the status of relics, cataloging them and labeling them in the museum collection, but this was only because of their connection to an artist whose hand may not even have touched them. It was a great opportunity, and I would love to do something similar at another institution.

PP: I heard through the grapevine you’ve just published a new book. What can you tell me about it?

K.A-S: Yes, my book On A Wet Bough, is available for pre-order now from Waltz Books, a small independent publisher dedicated to producing high quality photobooks.

The first edition of On A Wet Bough is a hardbound book limited to 1,000 copies. The book features 85 of my tintype portraits, drawn from ten years of my work in portraiture. It was hard to edit the project down to just 85 images, but I think we were able to put together a really compelling sequence of portraits.

PP: Thank you for your time Keliy