What is a JPEG? Everything You Need to Know

![]()

JPEG is, by far, the most popular image format for digital photographs and images in the world. An overwhelming majority of photos are stored and shared in this format, typically with a .jpg or .jpeg file extension, because it was a necessity of the early internet to keep file sizes smaller to enable faster transfer speeds.

Table of Contents

How Does JPEG Compress a Photo?

![]()

JPEG uses a discrete cosine transform technique to compress photographs. This same compression method is used in many different types of media, including digital images, video, and audio. Since light and sound exist in nature as waveforms, it makes sense that using frequency encoding is the best way to process this type of data.

JPEG compression favors the frequencies that are most important to human eyes. Since the eye is less sensitive to high-frequency variations, those areas retain less accurate representations, and an 8 by 8-pixel block is used to segment an image into regions with similar colors and brightness.

![]()

Information can sometimes be compressed with no loss, such as when using the popular ZIP format to send archived bundles of files over the internet. This can greatly reduce the size of documents and other sparse files that have a large amount of redundant data. Photographs are, on the other hand, typically densely packed with unique information that is difficult to break into repeating components for lossless compression.

That’s why lossy compression is needed to achieve dramatically smaller files. While no changes can be tolerated when decompressing an application or document, visual changes in an image might make little perceptible difference. This is the idea behind JPEG – to reduce the file size with minimal impact on image quality when used for sharing photographs for viewing.

Why is JPEG So Popular?

The early internet was incredibly slow by modern standards. Images were measured in kilobytes, not megabytes. Early dial-up modems used for the internet had a data rate of 56 kilobits-per-second. That means a 10-megabyte JPEG photograph would require at least 23 minutes to completely download. Clearly, image dimensions were very restricted to minimize file size and prevent several minutes of time spent waiting for a page to display content. Many web pages relied almost entirely on text.

![]()

Internet speeds have greatly increased but so have the resolution of images and amount of code required to display a modern website. Add to that the fact that JPEG is deeply embedded into internet standards and it’s easy to understand why it is still the predominant format decades later. There are alternatives and in the near future, JPEG might begin to be replaced with a more efficient format.

How Much Space Does JPEG Save?

The amount of space saved by using JPEG compressed images instead of a RAW file or TIFF is enormous, particularly when considering the pace with which images are being uploaded to the internet. Any reduction in file size and bandwidth for a single photograph can be multiplied by hundreds of millions since that’s how many images are shared on social media daily. Even in personal use, JPEG can cut the amount of storage used by 90%.

For a single 10-megabyte photograph, 9 megabytes of storage space can be saved, the upload will be faster and more efficient, and most importantly, every download will benefit from this reduction in power and bandwidth. A popular image that is viewed a million times will collectively save 9 terabytes of bandwidth. It’s easy to see how quickly this adds up to have a massive impact on the internet.

The Downsides of Using JPEG

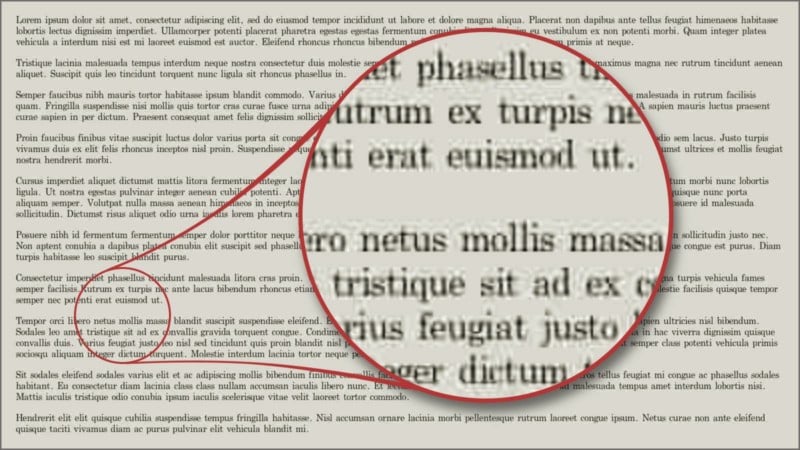

The purpose of a JPEG image is critically important in determining if it’s an appropriate format to use or not. Since JPEG is optimized for saving photographs, it tends to compress high-frequency data more strongly. In nature, one edge tends to blur into another and that is even true in photographs of manmade structures. Light reflects, bounces, and diffuses to such a degree that gradations occur, softening edges.

By comparison, computer-generated images can be unnaturally crisp with a large amount of fine detail. A page of text is a perfect example. Using JPEG compression on screenshots would be a bad idea since it would not be able to compress the data well without adding a large number of artifacts.

While viewing a photograph that is stored as a JPEG might be an ideal experience, editing the same image file could result in noticeable artifacts that were not present in the original photograph. Worse still, if a JPEG image is edited and saved again in JPEG format, the compression artifacts will continue to add up with pixelated images and block-shaped noise becoming overwhelmingly obvious.

![]()

This loss of image quality every time the JPEG image is recompressed is something known as digital generation loss. This is what it looks like when a JPEG is rotated and saved lossily 0, 100, 200, 500, 900, and 2000 times:

To minimize the issues of generation loss, images should ideally be edited losslessly before JPEG compression is used at the final step to export a web-ready file.

Finally, JPEG images don’t support transparency. While this isn’t relevant for a standard photograph, it is a useful addition when compositing photos, and being able to store a photo with a high-quality mask or alpha channel is very useful.

Alternatives to JPEG: JPEG 2000, HEIC, and WebP

JPEG is the leading internet image format and virtually every modern device supports saving and viewing images with this encoding. Its efficiency was surpassed several years ago, but it’s difficult for any new format to gain enough support to become as widely adopted as JPEG. That is slowly changing and it might not be long before JPEG is considered a format to avoid.

Every alternate format discussed in this section offers better compression at an equal or higher quality when compared to JPEG and allows including transparency as part of the image. In every case, widespread support is the only drawback to use.

WebP has risen to become a serious challenger to the dominance of JPEG. While the format might sound unfamiliar, WebP was released by Google as an open-source format in 2010. Providing an alternative and improvement over JPEG, GIF, and PNG images, WebP is the do-everything image format that seems likely to supplant JPEG someday as the first choice for the internet and possibly even for other uses. A photograph can be stored in WebP format using either lossy or lossless compression.

![]()

JPEG 2000 is a newer JPEG standard that was completed in the year 2000, as the name implies. It uses a wavelet compression method that is more versatile and can contain multiple resolutions and varying signal-to-noise ratios. This variability makes decoding an image in this format more complex and it hasn’t been widely adopted as a photography format. Its primary use, thus far, has been in a compressed video format known as Motion JPEG.

Apple made HEIC the primary photo format for the iPhone in 2017 with the release of iOS 11 and every Apple device with updated software can save and view images in this format. The format was developed by the MPEG standards committee and is not exclusive to Apple, although the iPhone maker is largely responsible for its success. It offers higher quality while taking up less space. While HEIC use is possible in Windows and Android, it isn’t as common. For photographers that use an Apple iPhone, iPad, and/or Mac computer, nothing special has to be done to use HEIC, making it an easy choice as a JPEG alternative.

![]()

JPEG’s Many File Extensions: It’s Not Just .jpg

JPEG files usually have a file extension of .jpg, however, .jpeg is not uncommon. Other extensions include .jpe, .jif, .jfif, and .jfi. These are all exactly the same and it’s usually okay to change the file extension. Since .jpg and .jpeg are the most popular, however, it’s probably best to use that ending to avoid any compatibility issues with apps that don’t recognize lesser-used extensions.

JPEG images can also be contained within other file types, such as PDF and Word documents. When a JPEG is loaded into an image editing app it is decoded for use. Saving as another format typically removes the JPEG encoding and the image will be recompressed or left uncompressed, according to the format that it’s saved in. This does not automatically remove any artifacts created by the JPEG compression or restore image data that has already been lost.

Who Made JPEG and Why?

JPEG was finalized as a digital image standard by the Joint Photographic Experts Group in 1992. This joint committee is part of larger international standards organizations, ISO/IEC and ITU-T. The work on standardizing photographic quality graphics began in 1983 and began narrowing in on JPEG as a good candidate soon after. The DCT compression algorithm at the core of JPEG and many other media formats was developed by Nasir Ahmed, an electrical engineer, and computer scientist.

The JPEG digital image standard was created for use in early computers which were primarily text-based at the time and images had a very limited number of colors and low resolution. JPEG began to change that and its growth was perfectly timed to assist with another new technology that exploded in the late 1980s. The benefit of JPEG image compression to bring photos to the internet is immeasurable and is also a great aid to photography in general despite its flaws.

Conclusion

JPEG format is both wonderful and terrible in equal parts and which side takes precedent is largely within the control of the user. If used wisely, JPEG can prevent wasting resources, both storage space and bandwidth benefit greatly from the use of compressed images. If care isn’t taken, however, and the format is abused, the resulting photographs will lose their integrity. Careful touch-ups done at or near pixel-level can remove JPEG artifacts and artificial intelligence can aid the process, however, the best use of JPEG is for archiving and internet sharing.

Original photographs are best stored in a higher fidelity format and, for important images, an uncompressed format should be considered since it allows the most freedom to use those photos in a variety of ways in the future.

Image credits: Header illustration by Videoplasty.com and licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0.