New Multispectral Film Scanner Is a Breakthrough for Analog Photography

![]()

Saskatchewan-based Film Rescue International (FRI) develops and digitizes old film, whether it’s rolls of precious family memories or vital historical archives in museum collections. To deliver the best possible results in an increasingly challenging, stagnant film scanning industry, FRI built a cutting-edge multispectral film scanner.

Multispectral Film Scanning: The Film Rescue Eye

Film Rescue International’s founder and owner, Greg Miller, first alerted PetaPixel about the multispectral film scanning project last fall. At that time, he was exploring how best to achieve his goals, whether through a partnership with an existing company or by building something from scratch. FRI opted for the latter option.

In the months that followed, Miller met Mattia Stellacci from the Technische Universität Berlin on Reddit, and the project to build a purpose-built multispectral photographic film scanner using available components entered full swing. Stellacci is a brilliant computer scientist with extensive experience in analog photography and film scanning.

![]()

After a considerable amount of time and money, the system is now ready. It comprises a Phase One IQ4 150MP Achromatic digital back, a Qioptiq Inspec.x L 105mm f/5.6 float lens, which is moved with extremely precise motors to both focus and enable scanning different film formats, up to 4×5, and vitally, a seven-channel multispectral light array. The lights, RRGBB plus infrared, illuminate the light table. There is a broad spectrum white channel for live view, and if desired, black and white scanning, although other colors could also be used for that, Miller says.

We’ll discuss the Film Rescue Eye — phonetically similar to Film Rescue International’s “FRI” acronym — system in more detail shortly.

As an aside, Miller says he floated the idea of calling it “POAM,” pronounced like poem. It’s an acronym for Phase One Achromatic Multispectral. In any case, Miller lauds Stellacci’s unique combination of multispectral scanning, how film is supposed to look, and engineering expertise. Miller says the new system would have been “impossible” to build without Mattia.

Why Multispectral Scanning Matters for Digitizing Film

As multispectral scanning pioneer Giorgio Trumpy (University of Zurich and NTNU) explains in a research paper co-authored with Barbara Flueckiger, by combining a monochromatic sensor and a multispectral light source with precisely-controlled red, green, and blue wavelengths, it is possible to digitize color photographic film with excellent color accuracy that requires minimal editing. Stellacci cites this paper, “Light Source Criteria for Digitizing Color Films,” as instrumental.

Many photographers who digitize at home use a digital camera with a traditional Bayer pattern filter array, which enables the camera’s monochromatic image sensor to capture color data. While this approach can be effective, it often requires photographers to manually fine-tune and color correct their digital scans.

Bayer pattern sensors are explicitly designed to digitally mimic human vision and capture images of the world that look “right” to human eyes.

“The core purpose of a digital camera is to optimize every single aspect from the hardware and software stage to match the human perception of color,” Stellacci explains.

However, that doesn’t align with how film works. For scanning color negatives, for example, it is not about what human vision sees on the light table, Stellacci explains, but what the photographic paper would see. The Film Rescue Eye’s RGB lights are finely tuned to match the spectral sensitivity of the photographic paper traditionally used to print color photos from film, essentially turning the digital sensor into a highly sensitive, extremely performant digital “paper,” albeit one that is significantly higher-resolution, versatile, and secure.

Basically, color negative film was not designed to be viewed directly, but rather to work in conjunction with photographic paper. Likewise, digital cameras are designed to match human color perception, not mimic film.

“Film has a certain way that it wants to be seen and a digital camera has a certain spectral response which is built into the Bayer pattern filter, and those don’t exactly align,” he explains.

Trumpy and Flueckiger’s research highlights a vital distinction between “information” and “appearance” purposes in digitizing film.

Stellacci emphasizes that it matters considerably whether the objective is to capture the appearance of the film medium at the time of digitization, or whether instead, the focus is on capturing as much information as possible that is stored in the film’s dyes. Stellacci believes, after considerable research and experimentation, that when the focus is on acquiring as much information as possible, the appearance aspect follows in kind.

And while Stellacci admits that all the required information is still there when scanning film using a Bayer pattern digital camera, it is not an optimized process, and it can take extensive work to achieve the desired results. This is not an ideal situation for a commercial enterprise like Film Rescue International.

With their new multispectral scanning system, Miller and Stellacci say they meet the film on its level, both in terms of the raw photographic data and the spectral response. They have created a system that “scans the film the way it wants to be seen.”

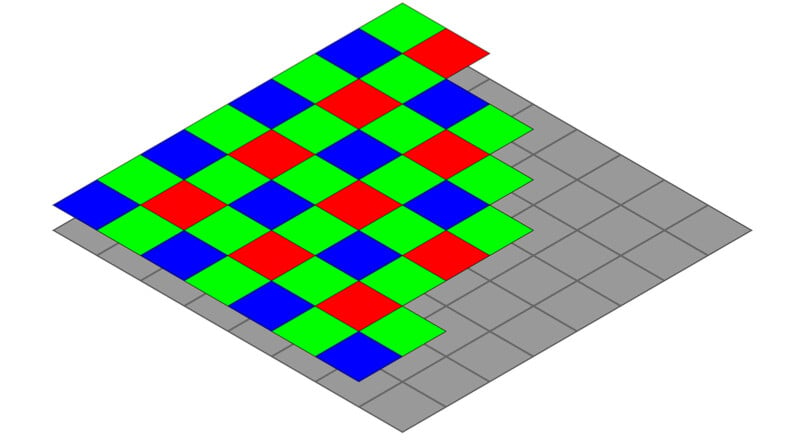

With a Bayer pattern sensor, each pixel captures only one color channel, and the sensor is comprised of 50% green pixels, 25% red, and 25% blue — human eyes are more sensitive to green. To ensure digital photos appear correctly, files are demosaiced to interpolate the missing color information, generating a full RGB image. Again, for digital photography, this is entirely fine.

However, for precise color reproduction when scanning film, there are issues. Colors shift, there are limitations in color resolution, and risks of false color effects and artifacts exist.

Color negative film records an image with cyan, magenta, and yellow dyes, which each absorb certain ranges of wavelengths of light. The precise behavior depends on many things, not the least of which is the film stock itself. Color print photo paper is made to be an ideal match.

‘… scans the film the way it wants to be seen’

When digitally scanning the legendary Kodachrome film, a commonly encountered film stock for Film Rescue International’s business, all these problems add up to present unique challenges.

Kodachrome routinely exhibits a blue color cast during scanning, as well as color fringing, halos, and other artifacts, all of which must be manually addressed, which is a time-consuming process.

However, the multispectral film scanner eliminates all these problems.

“It’s giving pleasant images really quickly,” Miller says. “What I’ve seen out of this machine is Kodachrome as Kodachrome should look.”

Miller tells PetaPixel that it is significantly easier to edit files from the new multispectral scanning system than any other system he has used.

“I’ve been having so much fun with this scanner.”

‘Kodachrome as Kodachrome should look.’

Stellacci credits this to the multispectral film scanner’s ability to capture massive amounts of information, which he says enables the color to “fall into place.”

![]()

The IQ4 150MP Achromatic sensor has no Bayer pattern filter — so it is a monochrome sensor — and it can capture a massive range of light data in each and every pixel. Each primary color channel, red, green, and blue, is captured in full for all 150 megapixels. Each exposure captures one specific color channel, and these frames are then combined to create a full-color image with extreme color accuracy.

But why not use a dedicated film scanning system instead? Film Rescue International has these, of course, but the highly specialized sensors in these machines are no longer in production. When a sensor malfunctions, it must be replaced with a used one, and sometimes these are not much better. This problem extends to other vital components of the scanners and will only worsen over time. Even routine service costs thousands of dollars, and the people who can do it are retiring. It is simply not a sustainable situation.

While Stellacci emphasizes that no part of the new Phase One Multispectral System, which Film Rescue International calls “the Pièce de résistance of modern film digitization,” is itself unique, the combination of all its elements is special. It represents a uniquely large step forward in digital film scanning, a field that has not experienced much groundbreaking technology in recent years, or even decades. It combines all the best, modern digital imaging technology into an easy-to-use, reliable, and exceptional system unlike anything else out there.

Pragmatism in Multispectral Film Scanning

Mattia emphasizes the importance of pragmatism for a project like this. He has been working on the project for the past few months, but has years of rigorous academic experience with film scanning. He says he created a film scanner with 80 different spectral bands, but “a lot of them, you don’t need.” He has also worked with systems using cameras with much smaller sensors, which then require tiling and additional motion components.

By eliminating dozens of spectral bands, the digitization process is dramatically simplified. And by using a camera with a massive sensor, tiling is entirely unnecessary (the Phase One Multispectral System scans at over 10,000 DPI for a 35mm frame). Furthermore, while academic research is not necessarily concerned with practical applications, Stellacci worked diligently to develop a system for Film Rescue International that would be efficient, consistent, and capable of operating within a semi-automated workflow.

![]()

The infrared light source is an important component, too, as it enables the use of software that can automatically remove dust and scratches.

The workflow is quite straightforward, although the hardware and software working behind the scenes are extremely sophisticated. Once the film is prepared for scanning — FRI does wet scanning — it goes into the appropriate holder above the multispectral lights, the Phase One camera, lens, and software work together to achieve optimal focus and exposure. Once setup, scanning each frame across all the color channels takes less than 10 seconds.

Stellacci aimed to eliminate as many bottlenecks as possible, from preparing the film for scanning to capturing the images and final output. The software he wrote to run the system provides all the controls Miller needs, ensuring that everything is seamless and the results are immediately excellent, with virtually no need for manual color correction.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Even if a Bayer pattern camera can ultimately achieve the same results as the Phase One Multispectral System, it requires extensive hands-on work. Although, for his part, Miller believes the Phase One Multispectral System offers better results than his new Bayer pattern Phase One scanning system, regardless of the adjustments he makes to the files.

Another benefit of the new system is that it can easily scan any format the FRI team can build a carrier for.

“This was a limitation with our Fuji SP-3000,” Miller says. “If you wanted to do any odd sizes, you had to jerry rig it into the system and you also couldn’t scan anything larger than 6×9 centimeters. We will be scanning everything from Minox to 4×5 as we get carriers built. There will be almost 30 carriers as we will a crop carrier and a slight overscan carrier for all formats.”

Incredible Film Scanning Performance

While Miller admits that many people want cheap, fast film scanning, he knows there’s an archival community that seeks the highest quality possible. He believes that’s where the Phase One Multispectral System comes in.

Given the cost of the Phase One IQ4 150MP Achromatic back itself, let alone everything else that went into the system, it is evident that Miller and Film Rescue International have put significant money into their endeavor. It is a big swing.

![]()

“This is the work I love doing,” Miller says, hopeful that Film Rescue International can capture a small part of the archiving market that wants the best quality available. “I love scanning people’s old negatives from the 40s, 50s, 60s, and 70s.” He says the older photos are typically so interesting, as photography was still relatively inaccessible, and people were so careful with how they shot every single frame.

When digitizing old film, whether they are family memories or significant historical moments, Film Rescue International’s Phase One Multispectral System is a future-proof, modern solution with incredible resolution and color rendering. The system meets FADGI standards, too, of course.

“We’ve strived to be at the top of the market for lost and found film processing and having a scanning system where we can say, in all honesty, ‘This is it, as good as you’ll get anywhere,’ is really important,” Miller says. He believes the new system cannot be beat.

“While all of the images in this article could be marginally improved with a digital edit, I felt it was important to present the scans just as they came out of the scanner, and for that, the results are exceptional,” Miller says.

‘This is the work I love doing.’

After seeing the system in action, carefully inspecting the very early results, and speaking to the minds behind the machine, Miller’s confidence is well-placed. Film Rescue International and Mattia Stellacci have created something truly remarkable.

Image credits: Film Rescue International