Webb Wears Two Hats to Photograph the Sombrero Galaxy

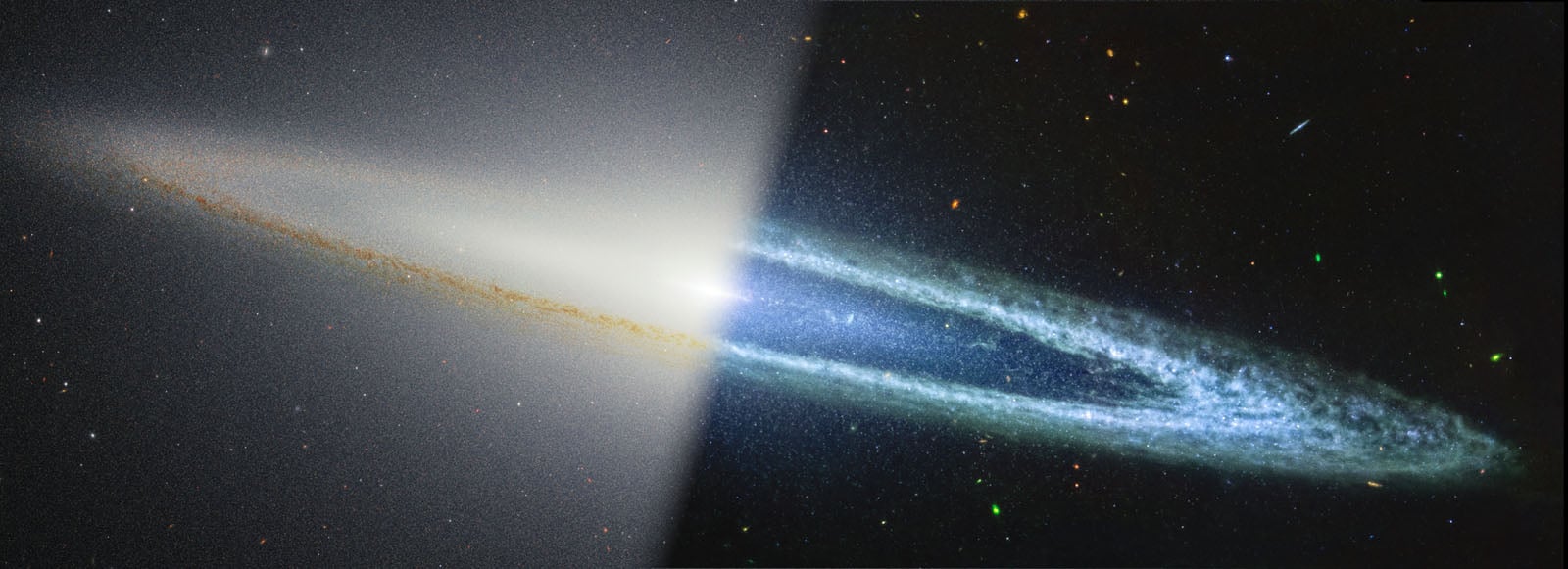

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) first photographed the Sombrero galaxy late last year. Months later, the $10 billion space telescope has set its sights back on the galaxy, this time at different wavelengths of light, completing a mind-bending photo of Sombrero’s galactic disk.

Last November, Webb imaged the Sombrero galaxy using its Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI). This image shows the galaxy’s core glowing in spectacular detail, an element that is impossible to see in visible light images like the ones captured by the venerable Hubble Space Telescope. At mid-infrared wavelengths, Webb can peer through much of the galaxy’s cosmic dust and debris, allowing scientists to detect and study carbon-containing molecules in the galaxy. These molecules, called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, can indicate the presence of star-forming regions.

However, the Sombrero galaxy, also known as Messier Object 104 (M104), is a “peculiar galaxy” that is not a particularly busy star-forming galaxy. The galaxy’s rings produce less than one solar mass worth of stars annually, less than half of what the Milky Way galaxy does.

While it’s essential to peer through some of Sombrero’s dust to better study the galaxy, it’s also important for scientists to see the dust in great detail to better understand how the complex combination of stars, dust, and gas is organized and how it formed and evolved. That’s where Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) comes in.

“The powerful resolution of Webb’s NIRCam also allows us to resolve individual stars outside of, but not necessarily at the same distance as, the galaxy, some of which appear red. These are called red giants, which are cooler stars, but their large surface area causes them to glow brightly in this image. These red giants also are detected in the mid-infrared, while the smaller, bluer stars in the near-infrared ‘disappear’ in the longer wavelengths,” NASA explains.

As is always the case with Webb’s photos of deep space — the Sombrero galaxy is 30 million light-years away — there are many very distant galaxies visible in the background. The redder they are, the farther away they are. It’s a treasure trove of galactic goodness.

Image credits: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI