‘Open Your Eyes’ Fotofestival in Zurich Shines Light on UN Sustainability Goals

![]()

Open Your Eyes is an outdoor photo festival in Zurich, Switzerland, until October 15, 2023. It is an effort to inform and understand the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) through photography.

The magic of photo storytelling converts the city into an outdoor gallery reflecting the UN’s message of no poverty, good health and well-being, gender equality, affordable and clean energy, responsible consumption and production, climate action, life below water and on land, and nine more goals.

We want to avoid what photographer Nick Brandt calls ecocide. “This is the murder of our home, of planet Earth – by us humans.”

The photos on display are not meant to illustrate the 17 SDGs but rather to make comments in the style of Hungarian-American photographer and Magnum founder Cornell Capa’s “Concerned Photographer.”

“The theme [of Open Your Eyes] was not decided by me or any art director,” Lois Lammerhuber, artistic director, co-founder and award-winning photographer from Baden, Austria, of magazine stories, tells PetaPixel. “It was decided by 193 member states of the United Nations. So, they assigned the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. It was approved and adopted by them.

“To have the environment of theory, brought together with the content of the SDGs, driven by world-class photography, in particular half of it is from TPS, The Photo Society, [a group of about 200 Nat Geo photographers] which means National Geographic heroes [photographers], the best of the best, the most talented. And I could even have, on display, a few works, which have been done 20 years back, 30 years back, and which emerge into a timelessness.”

Documenting Chernobyl and Human Degradation in the Soviet Union

Gerd Ludwig, part of the leading team of the NGO and festival who has been photographing for 50 years, feels he has opened eyes to the human environment in the former Soviet Union.

“I was basically the man on the front lines for National Geographic in the former Soviet Union for nearly 20 years,” Ludwig tells PetaPixel. “My first assignment for National Geographic, in the breakdown and fall of communism, was a seven-month assignment traveling in Russia, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine.

“It was a mixture of human and political degradation. The story was called Broken Empire, also the title of a subsequent book. I pictured the obvious changes in the former Soviet Union over the next 30 years in three major republics that stood for three different developments — Mother Russia, Kazakhstan, and then there was Ukraine, which was a split between East and West.

“When I first came to Chernobyl in 1993, seeing a post-apocalyptic world shocked me. But one must realize that this is often portrayed in a sense that is not doing it justice. We call it ruin porn. A lot of people just see the beauty in this. But I feel that it was very important not to get fascinated by a certain beauty that it has, but to show the horror behind it.

“I did not only focus on the environment itself, but also on the victims — those 500 to 800,000 including liquidators that were part of the cleanup. I photographed some radiation-be-damned people who returned to the zone to live their lives after being evacuated to anonymous city suburbs. As one person put it, they wanted to live on their own contaminated soil instead of dying of a broken heart in an anonymous city suburb.

“And I went deeper into the reactor itself than any Western photographer. I was in situations inside the reactor where I could only stay 15 seconds at a time. [He was pulled out by the safety supervisor when he was waiting longer for his flash to recharge.]”

Photographing Things That Are Not “Googleable”

Photographer Randy Olson founded The Photo Society a dozen years ago, which has a membership of about 200 National Geographic photographers. 60% of the photos displayed at the festival are from TPS, which, along with ETH, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, are partners in the exhibit.

“We’ve all got our kind of areas that we’re concerned about,” Olson tells PetaPixel. “Mine is extractive industries, and how that affects pristine ecosystems and indigenous cultures. But everyone, you know.

“What happens when you’re trying to pull gold out of all these places? There’s no place you can get gold anymore without hurting the environment. How do they affect people in ways that you can’t Google? You can still do work and find out things that are not Googleable. And that’s how I view my job.

“You know, I don’t want to go out and do things that anyone else can just look up on the internet. Much of the work with these extractive industries isn’t reported because they have the infrastructure to defeat mainstream media. And they’re spewing misinformation because they’re in news deserts… losing 60% of newsrooms and 80% of (news) photographers.

“The way AI will work out is that authenticity will come at a premium. Now AI is creating all this fake stuff, which is being leveraged… I see it as an extension of the loss of the professional (photo) journalist with a code of ethics.

“I’ve gone on a lot of expeditions with scientists — their knowledge goes very deep. Mine goes horizontally, and it’s more vignettes (which) are the most powerful way to get people’s attention. (What) I need to figure out through them which vignettes are the most compelling. And then I need to work as hard as possible to combat compassion fatigue and show that this could happen to you just like it’s happening to others.

“It’s a very different approach than science but the same mission. They know their stuff. We, as photographers, know our stuff, and we’re trying to collaborate using the best of our knowledge sets to achieve the same goal.

“I’m not real hopeful [that climate change can be completely reversed] because it’s not whether man is good or bad. But that man is innately selfish. If you think of our background, [it] is not even going back as primates, just as hunter-gatherers, we competed with each other. Who can kill more small animals with their hands and feed their families better? This kind of selfishness for survival, I think, continues in our more modern culture. And it’s a big problem when you ask people to be selfless to solve these problems. That’s, to me, a real uphill battle.”

“Nobody reads them [reports from scientific organizations]. They’re not mainstream. During that plastic story… it’s mostly how plastic gets into river systems, is unmanaged, and gets into the ocean and on our beaches. There were all sorts of scientific journals about how much plastic there was and what it would do to us. And no one was aware of it.

“The kind of catchy marketing line that came out from environmentalists was there would be more plastic than fish in the ocean by 2050. And that finally got people’s attention.

“Well, most mothers love their children. If you can tap into that with your skill set, like the main photograph used in that plastic story over and over in various museums, is a mother and child on a field of white plastic that they’re sorting. She’s teaching her child how to do this when he grows up.

“I’m no Eugene Smith, but what he did with his stories, like Minamata, which is not a pretty story, people being poisoned by mercury, is he felt he always had to have some iconic image that everyone could relate to universally. The mother in the bath with the twisted-up kid is recreating the pieta [a picture of the Virgin Mary holding the dead body of Jesus Christ in her arms], which is universal. Anyone who looks at that photograph will get that kind of connection.

“So even though what I was doing was not as powerful as what he was, I’m taking clues from his playbook and trying to go for universal human situations that everyone can relate to.

“In a story like plastic waste, the big dilemma is how pretty do you make it? It’s trash. But you’ve got to make it pretty enough and universally human enough that people will pay attention. But if you make it too pretty, you’re destroying the whole idea of why you’re doing the story in the first place.

“Nick Nichols exhibiting here [is responsible for getting] more parks in Africa, I think, more land than they’ve had before for parks.

“Photography exists in a kind of popular culture. And it can explain things faster than scientific papers that mostly scientists read. There isn’t a scientist that reaches 5 million on social [media] the way the nonprofit [The Photo Society] I started does or the million I reach. Between that and my own kind of thing, I can reach 6 million. And back in the print era, there weren’t scientists with that kind of megaphone, either.”

The Reality of Climate Change through the Extreme Ice Time-Lapse

James Balog, an environmental photographer based in Boulder, Colorado, has been at it since 1980.

“I was also a more traditional working photojournalist [earlier],” Balog tells PetaPixel. “But I had this vision that the best work I could do would focus on the collision between people and nature. And that a lot of it I would have to do outside the assignment system in the magazine system if I wanted to do the right thing.

“It was always a struggle. I would do the assignments to make enough money to survive. And then, whatever tiny little profits I had, I would use to go off and do my personal work.

“The Extreme Ice Survey (EIS) has had the most impact nationally in the US as well as globally. It is the study of glaciers receding because of climate change. It hit the world at the right time when people were thinking about that and wondering about it.

“It revealed something that you couldn’t see. People had been wondering about whether this climate change thing was real. Or were the scientists hallucinating? The EIS suddenly provided this first tangible, visual evidence of how the world was changing because of heat.

“EIS started with a New Yorker assignment in 2005 and continued with the National Geographic assignment in 2006. It then turned into the time-lapse work known as the Extreme Ice Survey in 2007.

“And then we did this documentary film, Chasing Ice, in 2012. It hit New York City less than a week after Hurricane Sandy. The media and cultural capital of New York was all aflame with the anguish of dealing with Hurricane Sandy, and these pictures came along talking about water and melting glaciers and climate change. And it fit into the zeitgeist of the time.

“Leonardo DiCaprio ran it out on his social media, and we were getting millions and millions of followers in a matter of a couple of days — it was incredible.

“Most people have never been and never will be to a glacier. But the pictures make it tangible, real, and alive. And that’s, that’s the power and magic of photography.

“The Moving Picture,” the cinema, also has a powerful effect. And I’ve always thought I could do that through cinema and film. But it occurred to me last night that photography is unique because it’s a moment.

“Cinema is a constructed story. And so, the viewer can always mentally pull back and go, ‘Yeah, I don’t know, the guy invented the relationship in that scene’… But in still photography, it’s much more precise. It’s like a stiletto, a knife going into the world and saying, I got that right there. That’s it, period. And it’s the decisive, singular capture of time. That makes still photography incredibly emotionally potent.

“I think there is potential for a broad swath of the human race to use their cameras on iPhones or by whatever other means they have to tell the story of what’s happening right now. We’re doing a series of pictures that we expect to go on for 100 years in Iceland. Most of those pictures will be made by tourists visiting the edges of these receding glaciers, and they will put their iPhones in these cradles and monuments that we’re setting up. They will help us make a visual record of those glaciers retreating.

“Human eyes have never had a chance to record everything around us. Because there haven’t been as many cameras, and that gives us, as a species, an opportunity to record more than we ever did before.

“It will be possible to reverse the environmental damage only over a very long time with an amazing amount of work. I think the immediate reality in front of us is that a lot of damage will continue, creating chaos in our immediate and near future.

“However, it’s better to do what we can to retreat from our bad habits than to do nothing. We’re doing it for the people who will inherit this earth. I try to show people that we have an ethical obligation not to completely screw this place up and leave a burning wasteland where there used to be green grass and beautiful trees.

“I started on this quest in 1980, not knowing I would be on it for the next 43 years. And in the beginning, I defined all of this in my mind as being about the collision between people and nature — about these two opposite things. And what I’ve come to realize in recent years is that we are not two opposite things. People are part of nature. We are an element within nature, just as the earth, air, fire, and water are. I’ve unpacked that in my most recent book, The Human Element.

“What we’ve not understood is that we are part of nature. We’re not separate from nature… the more we know that, the more we realize that we’re hurting ourselves when we damage things like blue whales or receding glaciers or forests.

“Digital Photography has been a tool to help with this mission. It’s made time-lapse, practical, and possible. We could never have done it if we had just been in the film age.”

AI has Created More Imagery than in the Whole of Photography

“I’m not a photographer, but I work in photography,” Lars Boering tells PetaPixel. I’m an advisor. And I’ve always run cultural organizations, including World Press Photo, for six years. I’m a photo enthusiast.

“But I see my role more in supporting the visual storyteller, which is a better word than photographer. I’m the director of the European Journalism Center in The Netherlands.

“My original thought to bring in the social sustainability goals in this Open Your Eyes exhibition was the start of aggregating stories that matter. I have always believed that photography should be about something. If it’s not about something, then what is it?

“I think we are in an age where visual communication [and] visual journalism has become the most prominent form of communication. Still, photography is an excellent way of getting people to look and stop and think, ” Hey, what’s the story behind this?

“I don’t think a single photo, or a series of photos, has ever changed the world in a big way, but it has definitely played a role. For me, it’s more the combination of visual stories that can emphasize a challenging situation, something that needs to change, to get the audience’s eyeballs on it, and to get politicians or opinion makers to see it is the most crucial task. It’s out of the hands of photojournalists.

“If we want to talk about a filter that changes something, we have to talk about one of my favorite photo series, Finding Freedom in the Water of Anna Boyiazis.

“She tells a story where women teach other women to swim on the island of Zanzibar. Many women drowned before because they weren’t taught how to swim. This picture shows that fewer people drown when women take charge and [in this case] teach other women to swim.

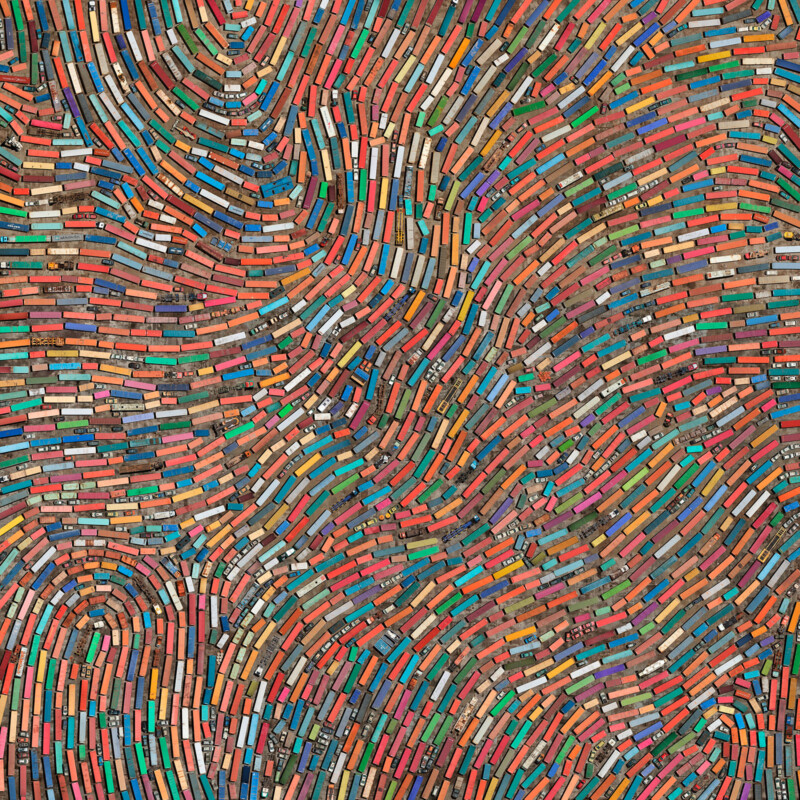

“Let’s take the work of [Edward] Burtynsky about the planet, the Anthropocene Project displayed in many places and books [which shows human influence on the future of the earth.] That is one of the examples where a mass audience gets to see it and understands that we have to change. One of the main drivers of this is National Geographic or Geo [published in Germany] magazine.

“In the 90s and early 2000s, people realized we are taking too much fish out of the sea. We are changing the planet drastically. [In] the last 20-30 years, photography like that has helped create more awareness worldwide.

“In the last months, more imagery has been created by AI than in the whole history of photography combined, including digital, which is massive. So undoubtedly, AI-generated imagery is playing a role, but I would say that trustworthy photography made by a real person will stand out from all these illustrations and generated imagery that we will see more and more.

“People always talk about shooting on film — it’s sort of nostalgia that plays a role, but [what about] the amount of chemicals, the production costs of the stuff we need to use to produce films?

“I think digital also has its effect, right? Because energy and storage also have an impact. But we don’t need these chemicals anymore. We don’t need film. The most significant contribution of photography to the environment has been moving from film to digital.

“There is talk about young audiences needing to do this or be taught. I totally disagree. A generation has grown up with the screen and is all about visuals. It’s all about moving images that communicate through photography… it is we who need to realize that there’s a new way of looking, a new way of experiencing imagery, and they will not adapt to us. If we don’t adapt to them, we will lose the connection.”

Merging Photojournalism and Science to Help People Living on $1/day

“I have a sensitivity to the disadvantaged people who are the voiceless,” Pulitzer-Prize-winning documentary photojournalist Renée C. Byer tells PetaPixel. “[It may have] to do with healthcare, homelessness, or extreme poverty. I try to give a human face to staggering statistics, like about 1 in 6 people live on $1 a day — now it’s 800 million people.

“When people are looking at my images, they can almost imagine being in the image and experiencing the life of the people I photograph so that they can have a shared humanity and compassion for people who may have a very different life than the one you or I have.

“[I am] opening the eyes to the fact that there is a huge population that lives in extreme poverty who many people don’t even know exist. So, my challenge is to connect them so they can respond to the images.

“Science is a fact. And as a photojournalist, I’m very fact-based as well. I have ethics, and all the images I take must be correct. When you merge science and photojournalism, this amplification is promising for the world.

“And, here in Zurich, I feel like this is a purpose we have never ventured into. The future has a lot to do with science and technology, and I feel like photojournalism can help amplify that and bring the world to a deeper understanding of what science is trying to do.

“I think photographs can impact change, especially photojournalism, not just photography. Photojournalism is completely different than photography. In photojournalism, you have ethics, and you have to have truth, and you have to have value. And I feel like when you bring that to the table and work as a partnership with science, it’s a very much-needed solution for our future.

“It’s when I showed a photograph of a solar-powered shower, where children who had never had showers or anything, because of science and technology, could have a shower, giving them a respite. When you bring an element, like solar-powered showers, to an encampment that’s elevating the health of these children — in India, when it’s 112 degrees.

“When you look at an e-waste dump site, think about your TV and computer. What happens to that after you’re done with it, and you throw it away? Where is it going? Well, it’s going to places where children are burning plastic to try to find little metals so they can recycle them.

“That is very hazardous to the environment. We think about technology as this great tool, but we never think about it as where children work and suffer. So, we need to look at the whole perspective of technology and its impact.

“The partnership of science and photography is an essential movement because photography can amplify really good science. It can also touch our hearts and give us feelings about situations that could help us have a deeper understanding of the role of science.”

stop. think. feel. act.

“The cover [of the Fotofestival catalog] tells it,” says Lammerhuber. “It’s all about the next generation, about our society’s heritage. And the young people, when they Open Their Eyes, must decide. This picture is called Ena Holds the Sea by Cooper and Gorfer, Fuji Ambassadors from Sweden.

![]()

“That’s the girl’s name, and she holds the sea, the ocean. And the ocean is, of course, where all life comes from. And it’s about the decision if we go on or not. So, if she gives back the fish or not.”

“There is the story somewhere in southern Italy,” says Ludwig. “A lot of starfish washed up on the shore, and it was thousands of them. The kids ran to the beach and threw them back into the water one by one.

“A couple of old men standing there with their hands in their pockets said, ‘Kids, what are you doing? It’s thousands of them. You won’t make a difference,’ and were shaking their heads.

“One of the kids turns around and has one starfish he is taking back to the water and says, ‘It is making a difference for this one.’

And so, I see my role and the role of photographers in incremental small changes that make a difference — one person at a time.”

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at The International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him here.

Image credits: Header photo: Ena Holds the Sea © Cooper & Gorfer (left); © Renée C. Byer (right). All photos courtesy of Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich) and Open Your Eyes, FotoFestival, Zurich.