How the Official Coronation Portraits of King Charles III Were Shot

![]()

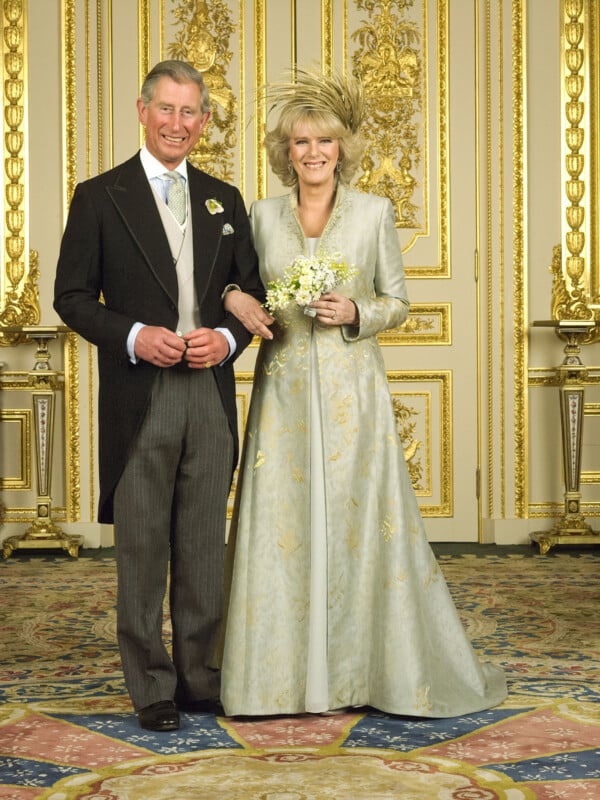

Hugo Burnand, the photographer who captured the official photos of the coronation of King Charles III and Queen Camilla last May, has also photographed their wedding in 2005, the king’s 60th birthday in 2008, and the wedding of Prince William and Catherine, Princess of Wales in 2011 and many other royal events.

The Most Important Portrait on Coronation Day

The coronation portrait of King Charles III was the most important of the day, so it was imperative to know you had a good expression.

“I know when I’ve got there because I have this strange characteristic,” Burnand, 59, tells PetaPixel, after completing the most important assignment of his career. “I don’t do it consciously but start clicking my fingers. And I know I’ve got it, generally, once I click my fingers with excitement. I’ll then go a little bit further, you know, the backup, the insurance, before we move on to the next.”

“On a private, very private shoot that hadn’t had three days preparation, I would have taken many more images to get the perfect one. But on this one, the precision of the shoot was so well rehearsed and practiced that we got there much quicker.

“We rehearse with a variety of people, basically whoever is around, and it’s really important… I’ve discovered it over the years; I should have found it long ago. If you have a young, good-looking assistant who stands in for photographs that you’re taking, it’s generally a disaster because those young, good-looking [people] look good in any light.

“I have a large canvas I painted years ago for a portrait shoot. It’s almost like a theater backdrop, and since we knew the dimensions of the robes, we used that backdrop [as a test robe].

“We tied it on to whoever was being the standard [test subject] so that we got a feel for the weight of the cloth and how it would position itself. It’s important because, in this picture, the robes make a part of the portrait. The robe is an incredibly important part of the structure of the picture, so we needed to have that visual reference while rehearsing.

“There was the dresser [to arrange the robes and clothes]. The crown jeweler was there for the crown, scepters, and the orb.

One Hour of Photography, Days of Preparation

One would think that official coronation photos would take a long time to execute, with the official robes to be placed precisely in their proper place, the crown jewels to have the right shine, the backgrounds to be depicted, the group photos, and above all, the correct royal expressions. But no, the photographer was given just one hour, and he delivered.

“We had roughly an hour, and I always say I would love more time, and they would have loved less time,” says Burnand, born in Cannes, France. “We set up all the lights, cameras, and tripod, and we’d done these run-throughs. But while it’s all completely perfect, technically, you still have to allow the characters’ emotions to come through in the photographs, and that is something that you can’t stop-watch.

“To be really honest with you, they wanted us to do it in about 45-50 minutes, but I always said, ‘Listen, it’s gonna be about an hour,’ and it was more or less an hour from beginning to end.”

The big group took the most time of all the photographs.

“Of the official photographs, this [holds up the group photo] is probably the one that took the longest…because of the sheer number of people in it,” says Burnand. “But we were very well organized, and they were all in position quickly.

“It probably took us some time to get these robes into the right position. Here we have Princess Alexandra, a cousin of the queen — a wonderful working royal, but she’s pretty old [born 1936] now. So, we’ve had everything until the moment we’re going to take the photograph and then asked her to step forward because she’s been sitting down…and then she just came in.

“This photograph took longer because this was so important to the angles, line, and position, although the dress rehearsals are stop-watched [literally]. It’s from beginning to end, and we don’t worry about each photograph and its own time.

“They will be ready when they’re ready because I can’t stress enough how important it is to photograph the individual rather than just the lighting, the line, and whatever else it is. It’s the emotion that you need to get through.”

The Essence of a Great Portrait

“It’s really important the emotion we can photograph in an individual,” says the photographer. “While there were many somber aspects today, it was a day of celebration. I had jellybeans which are well-reported. I had a big jar of jellybeans, which is my trademark reward because not many people say no to a jellybean. That is the atmosphere I like to create — it is a happy place to be.

“What I would like people to do when they look at a portrait that I’ve taken is I’d like them to feel that they are in some form of conversation with the person in the picture. I would like them to feel to be arrested by that photograph, and I think the only way you can do that is by being in good communication with them [the sitter] yourself.

“To a degree, photographers are actors, and I’ve talked about the theater of the whole shoot before, but if you have things in common with them, it’s much easier to get into their collaborative conversation.”

Setting Up the Cameras for the Coronation

Burnand set up four Fujifilm GFX 100S cameras on tripods the night before, with all the batteries fully charged and everything locked and loaded.

![]()

“Right now, here we have the 110mm [holds it up], but for the coronation, we had 20 lenses in the room,” says the photographer with a Royal Warrant. “We had this thing where we have the backup in case something goes wrong, and we also allowed ourselves the luxury of a backup for a backup because, you know, with that time frame and that schedule of photographs, we couldn’t allow for suddenly having to shoot on a whole different lens. So, we had the full range of Fuji lenses.

“I went with Fuji as they have quite a good green policy. I will support anything with a green conscience, and Fujifilm does as cameras go. It would be worth double checking, but what I understand is when Fujifilm worked out that film was going out of fashion, they employed their workers who were making the film to get into creating a [digital] camera, so this camera has come from camera photography people rather from the digital world, and it’s a little detail. Still, I like that sort of thought process.

“We tried, when possible, to be on 100 ISO, but those palaces have big rooms with a lot of silk on the walls that sucks up the light, and we were pumping out quite a lot of light.

“It came to the point where we were thinking, ‘Okay, we’re gonna do 200 ISO.’ I think we might have gone to 320 ISO and, in one stage, to 360. [However], we started at 100 ISO on everything and only moved up if we had to.

“It [aperture] varied from picture to picture — when you want the background to be in and when you don’t want to go on the background. When you’ve got the crown jewels, you don’t want too shallow a depth of field because there’s so much to have in focus. So, each one was tailor-made, but we use around f/8 or f/9.

“I don’t [look at the back screen to see the result]. I still love to get my eye up to the lens as you need them to look at you, not above or beside you. I use the camera in a very old-fashioned way. Now we were shooting tethered on this particular shoot on every [photo], so I always had an assistant doing the chimping for me.

“I had to trust myself. I had to trust my team, and I didn’t want to waste any time that was so valuable to communicate with my subjects — just the pressure of time and the necessity to keep a 100% connection with them.

Lighting His Majesty

The coronation photos were all shot with diffused flash and no available or continuous light.

“It was bespoke lighting for each picture, and so this one [King Charles portrait] here, I wanted a painterly look, a mature look, so there’s a little bit of Rembrandt lighting coming in. That was very intentional, and again the room behind, we dropped [made it go dark] it right down. It was risky, but I felt it was a risk worth taking.

“We were using Profoto lights, and we had eight different setups. A few lights were moved and used for different setups, but they were only twisted, or the power sliders were pushed up or down.

“This [Queen Camilla] was in the green drawing room next door, and I wanted to give her more light. I’m pretty honest in my photography, and also, we have no time for any major editing, so what went through the lens is what we had to present. We had 12 hours, let’s say 24 hours, to prepare everything for the press.

“You can’t see [but there is] an enormous scrim, so it was like three French windows of light coming down and then other lights to light the room in the back, and then this [King & Queen] is the same setup as the one of the King on his own in the throne, but we lifted the light in the room to give a sunny effect.

“Here again, basically the camera is more or less in the same position as the [earlier photo], but we’ve changed the lens, and this one was specifically designed to get as much of the architecture of the palace in as possible, and again we wanted the room to feel like it was being lit through the windows and we cleverly bounced daylight left, right and center. It looked like a NASA Space Center with all the satellite dishes we were moving around.

“This [earlier group picture] is interesting because these are the steps to where the thrones normally are in the throne room. Most of the photographs at recent royal events have been taken with everyone standing on these steps, so you end up with just these dark heavy felt curtains as the backdrop, and they absorb the light and are not very exciting.

“And so, when there are a lot of people in the picture, it’s a suitable place to photograph them, and also you get the gentle arc of the steps creating rather a nice line. Also, those steps gave a fantastic opportunity for the cloaks to be illustrated, but it also means you can get the architecture in, and it sits comfortably within the picture. Lighting again bespoke for each picture, and there was a story to be told with each picture, and the lighting was set up accordingly.

![]()

One would think that royalty would be overwhelmed with so many flashes going off in their faces, but apparently not.

“I think they’re quite used to it,” says Burnand. “it’s a bit of theater. I think people like to have the flash based on a handheld camera or in the studio because it keeps them as a part of the story. In contrast, if you’re silently behind a silent camera and nothing is really going off, I think it’s more difficult for them to join the portraiture tango.

“You leave them too much on the outside, so I don’t have a problem with flash, and they’ve never seemed to have had a problem with it. We love using daylight when available, but you know the daylight in England is just so unpredictable and changeable and variable.

“I grew up learning black and white photography from my mother at home. I love daylight and adore daylight, but I think that’s one of the things English photographers have to learn to use, lights. The more I can make it look like daylight, the happier I am.

“I must have had two or three [flash heads] in the background, one or two main lights, and one fill.”

![]()

Assistant Luis Ureña (extreme right in cycling photo) helps out by adding that there were about eight heads in each shot, and they had about 30 Profoto packs.

“We used a giant silver parabolic reflector of 240 cm [~8 feet]. The scrims were maybe 10 feet by 15 feet,” says Burnand. “It was a lot of equipment we had, and because we don’t have that much in stock and also you need backup [we had to rent].

Here is the massive lighting rental list:

“I haven’t checked that, but I’ve always been told that Cecil Beaton’s [the photographer of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation] reflection is in the orb (a golden globe surmounted by a cross placed in the hand of the monarch that reminds the sovereign that their power is derived from God) of his photograph of the queen.

“It would have been nice to have repeated that signature, that sort of Hitchcockian appearance. But with the lenses, we were shooting on and the distance between me and the orb, there was no way I would ever feature on it.”

Burnand worked with a team of five assistants, including his daughter Una. It took the team three days to rehearse and set up the sets with a camera and lighting.

“We set each one up around the palace,” says Burnand. “I was trying to think of how they would react when they walked in and how the whole thing would unfold. It was like a continuous line from one photograph to the next because those robes are heavy and ungainly, and you don’t want to walk back and forth too much. We set up each little studio and lighting rig, and then the job was to try and marry them all together into one continuous piece of theater.”

There were eight different sets. Burnand often handholds the camera depending on the individual, but on this particular occasion, the precision was like a military operation, so each camera was fixed in a position [on a tripod] so that there was minimum movement between each shot.

Burnand shot in autofocus, ensuring the eye was focused on each shot.

“The technology [AF] is great, but it does let you down sometimes,” admits the royal photographer. “What I loved about the Hasselblad and the 12 exposure film backs is this rhythm to a shoot, and you can pause and talk while you changed film backs.

“Now with digital [it] is just like shoot, shoot, shoot, shoot, and I don’t think it is as productive as having a rhythm, a communication, and a pause in between photographs. So, I will probably bring that rhythm from film days into digital portraiture.

“Having photographed them [Charles and Camilla] for nearly 20 years, we have excellent communication, and certainly, it is a collaboration between us when we photograph. It’s not just the photographer’s view. If he comes in and is in the wrong position, we’re gonna ensure he’s in the right position.”

When Burnand first meets the king, the address protocol is “Your Majesty,” and after that, as he keeps on talking during a shoot, it’s “Sir.”

![]()

Turnaround Time for the Coronation Photos: 24 Hours

Coronation does not have to be turned around in minutes or hours like press photos, but it is still a stressful day to do so.

“We got home at five o’clock in the afternoon, and we had to deliver them by four o’clock the next afternoon,” says the royalty shooter. “It was a massive, massive challenge; I have to tell you.

“We downloaded the images. We did our first selects. We had a cup of tea. We then went through the selects again and whittled it down to what we felt we should put forward, and obviously, we had to put options forward. It wasn’t wholly my decision, so there were variations of this image [King] and of all the others. I think we edited to about 18-20 images.

“We had four of us in my kitchen. We had four screens and four computers, and I did the final polish and the finishing off. Normally I’m the one with Luis. We do it all ourselves, but [this time] two other team members, Ian and Rob, were also involved so we could get through it as quickly as possible.

“We had a call from the palace at, I think, about ten to four saying something along the lines of ‘The deadline is getting close,’ and I said, ‘Yes, but I’m watching the wheel of WeTransfer whirring while you call me. I don’t know how long it’s gonna take, but they’re on the way. So, I was really happy to get them in there before the deadline passed, but it was touch and go.

![]()

![]()

Burnand shoots in RAW. He shoots on both cards and tethered and saves them to the computer.

“We have shot JPEG only by mistake,” he admits.

“We tether with Capture One, and then we move on to Lightroom to organize all the photographs, and so it’s a mixture of Capture One and Lightroom [and then Photoshop],” says Burnand’s assistant Luis.

“16-bit color. It’s also because it’s a medium format file, and they’re quite big, about 200 MB per file. It gives you a really lovely color depth and information. Why not shoot in the highest quality that you can? This Fujifilm camera can shoot on 16-bit [RAW].”

“We gave them [the Palace] small and big sizes because they will pass them on to the TV stations or the newspapers. We tend to give them the full rez file in TIFF or JPEG. [And small] jpegs for emailing. We do a mixture of Adobe RGB for magazines and sRGB for emailing or social media.”

“When Hugo got the email from you at PetaPixel that you wanted to interview him, I almost cried,” says Luis. “And that’s really true because I follow your website. I have Flipboard on my iPad, and I like reading all the articles you publish. As a photographer, I was very proud when you contacted him and recognized us.”

Official photographers of US presidents and vice presidents are not allowed to delete any photos, whether out of focus or with the subject badly cropped or anything, said David Lienemann, who was Joe Biden’s official photographer when he was vice president to PetaPixel.

But Burnand has no such rules and occasionally deletes photos that are not good.

“But I don’t like deleting because I like the story,” says Burnand. “Sometimes we delete mainly for storage because you know there is stuff that you don’t need. You know, it’s like having the negative contact sheets. It’s fun to run your finger up and down and see how you got that.

Hiring Your Mother as a Photo Assistant

Burnand, with wife and kids, was holidaying in a remote part of Bolivia in 2005 when they were robbed.

“We were a family of six people in the high Andes of Bolivia, and we only had $35 in our hand. We had no passports, no Cashpoint [like ATM] cards; we had nothing. Back in those days, we were traveling with cash, and I think we had $5,000, which had been stolen, and we trundled off in the night.

“The Internet was pretty fresh in 2005, it wasn’t something we all depend on like these days, and we certainly didn’t have mobile phones. My wife said, ‘What are you doing?’ as I was going on the Internet, and I said, “I’m going to see what our insurance says, and she said, “We don’t have any insurance,” which was true. I repeated, “I just got to do it, I just got to do it, I don’t know why.

“I hadn’t been on [email] for 15 days, and this email had been sent literally hours before [asking] if I could photograph the wedding of Prince Charles and Camilla.

“I said [responded to the email] I couldn’t do it and went off into the jungle with the children and my wife. I became very ill with amoebic dysentery, and while I was lying there sweating, I thought, ‘I’m gonna die here, and if I don’t die here, I could photograph the future king of England’s wedding. I need to get better right now.’

Burnand did get better and sent out a message that he was accepting the photography of the royal wedding. He also called his mother a photographer and asked her to help with the wedding photography.

“I asked my mother, a photographer if she would help organize the wedding, which she never fails to remind me is quite a big ask of a child from Bolivia and say, ‘Oh mum, can you organize a royal wedding for me?’

“She [Burnand’s mother] was an assistant of mine at that shoot, and Prince Charles, as he was then [called], liked the idea that there was his family on one side of the lens and me and my family on the other.

“My mother [she also assisted at Prince William and Kate’s royal weddings], now 83, declined to be an assistant on the coronation. My middle daughter, now 25, and of my four children, is most interested in imagery, photography, and movie making. She’s a very good documentary maker, and I asked her if she would be one on my team. So, there’s always been a part of my family on these really big occasions.

“They’ve employed me because they know me, trust me, and know what they’re going to expect, so I have to be very much that person, and having my team around me is important.

Getting Into Photography

Burnand started early, winning his first photo contest at Cheam School, the same Hampshire prep school attended by the King and his father, Prince Philip.

“I won my first photographic competition at age seven on a camera [a birthday present] bought by my grandmother in the local chemist,” Burnand distinctly remembers, although he does not know the model. “It was black on the front with a strip of white plastic across the top, one lens in the middle, and the viewfinder right above it.

“I went to Harrow [a boarding school] afterward, and the old boys of Harrow include William Fox Talbot, who we believe invented photography, although, in France, they think it was someone else [Louis Daguerre].

“Cecil Beaton [invited by Queen Elizabeth II to photograph her coronation in 1953] went to Harrow, and Patrick Lichfield [who was the official photographer at Prince Charles and Diana’s wedding] also went to Harrow and a number of other photographers as well.

“Soon after that, I must have been given an Olympus OM1, which I still have.

“I learned photography because my mother was a photographer. In the evenings, she used to blacken out the windows, turn off all the lights in the kitchen, and put on the red light. Then she would set up the enlarger and the dishes of chemicals on the kitchen table, and I would sit under the table with our dogs, just talking and chatting to the dogs listening to those trays, the noise of the solutions going back and forth.

“I have used the 35mm range of Canon. My last one was the Canon 1DX Mark III. I kept using them, but I’m not big on insurance. I self-insured and found that it’s time to upgrade when it hits the floor and smashes or just runs out of steam. So, I’ve sort of been through the full range.

Burnand graduated from the Irish National Stud breeding course.

“At the age of 27, I was following a career in the world of racehorses and bloodstock, which is a passion of mine. I love horses and worked at Lloyds of London as an insurance broker. [One day] I decided that I would stop insuring racehorses and would insure something which would earn me a bigger premium.

“Unfortunately, I wasn’t very good and got fired in eight or nine months. It was a fun job where my title was North American medical stop loss liability reinsurance broker, and I had no clue what I was doing.

“I spoke to my girlfriend, who then became my wife, and said, ‘I’ve just been fired,’ and she said, ‘Ah, now you can be the photographer you’ve always wanted to be.”

Many photographers have inspired Burnand, but the work of three of them has influenced him a lot. And the fourth is Sebastião Salgado.

“My top three: Richard Avedon, Jeanloup Sieff, and Irving Penn, and Irving Penn is my hero. Penn was a photographer purely for the love of photography, and he had the advantage of being a photographer in an age where you didn’t get pigeonholed, enabling him to take the photographs he wanted. He was fundamentally a portrait photographer, but he took portraiture into different areas, obviously ending up in fashion, but even his still lives were portraits of inanimate objects.

Now that Burnand has photographed the “Gig of the century,” he would like to turn his attention to capturing portraits around the world of people that inspire him.

“I’ve just always loved portraiture, and from now on, I would like to photograph icons worldwide,” says Burnand. “People who mean something to me, and Sebastião Salgado is someone I would like to photograph. I would like to photograph President Zelensky and Stevie Wonder.”

You can see more of Hugo Burnand’s work on his website and Instagram.

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at The International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him here.

Image credits: All photos courtesy Hugo Burnand