The Inside Story Behind Curiosity’s Time-Blended Mars Panorama

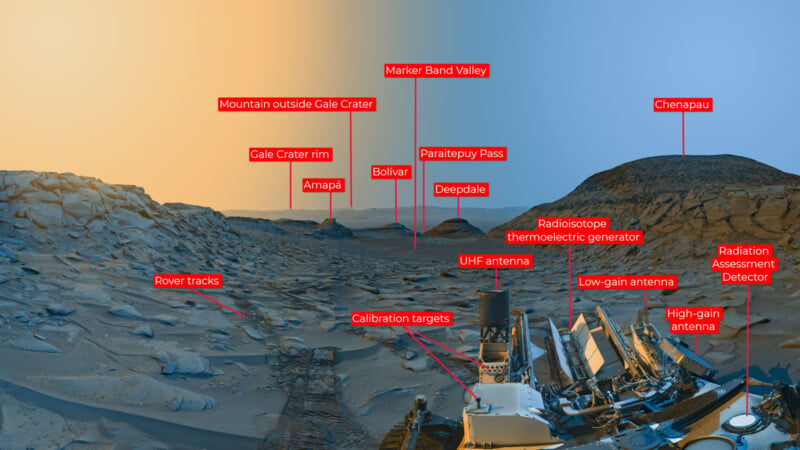

Earlier this week, NASA shared an incredible time-blended composite panorama its team captured with Curiosity’s navigation camera. PetaPixel spoke with Doug Ellison from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in southern California, the man who planned, captured, and processed the photos to make the “postcard.”

Capturing the Martian ‘Postcard’

“Postcards” aren’t new to Curiosity or NASA’s other Mars missions. They are a striking way to show the beauty of Mars and engage the public in ways that highly technical scientific images can struggle to achieve.

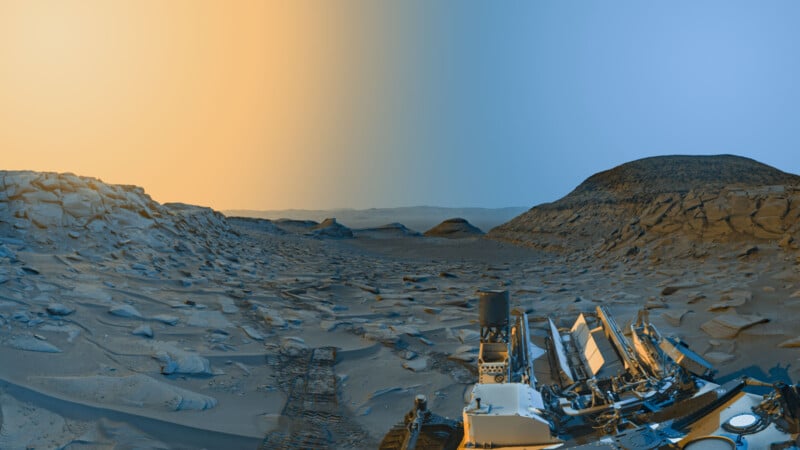

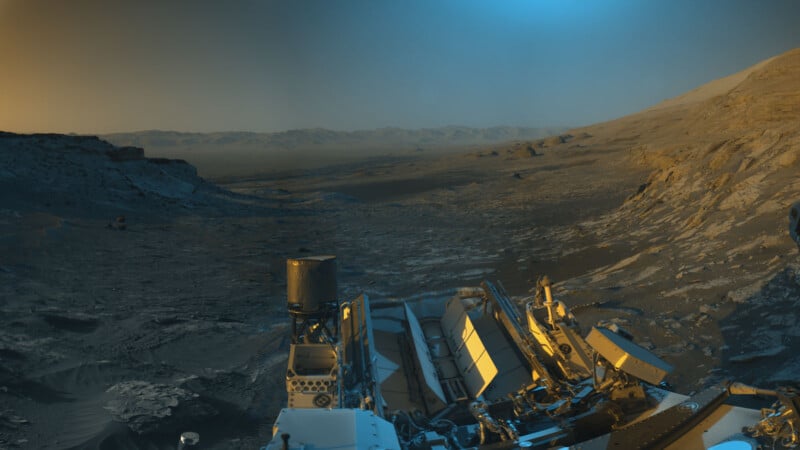

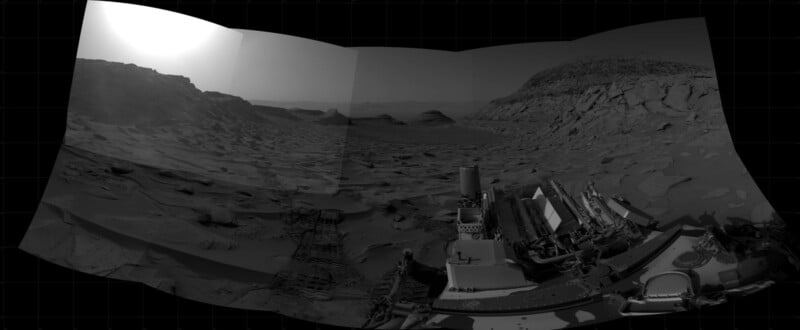

However, the latest postcard of “Marker Band Valley” on Mars achieves something fresh by combining views of Mars from the morning and afternoon, although as Ellison tells PetaPixel, the afternoon image was captured first.

Years in the Making

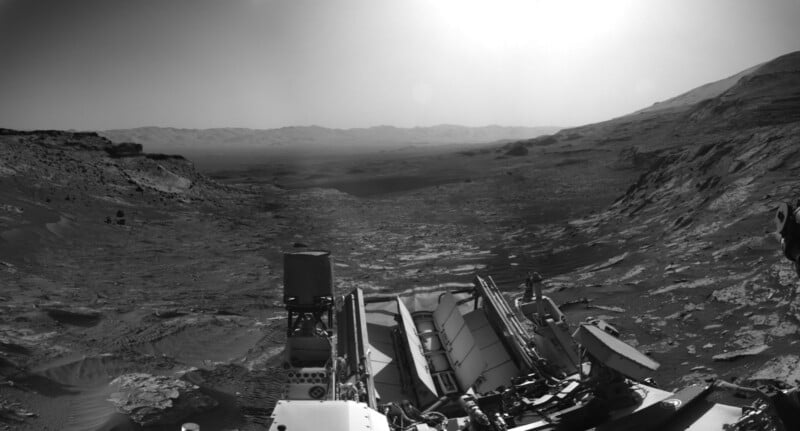

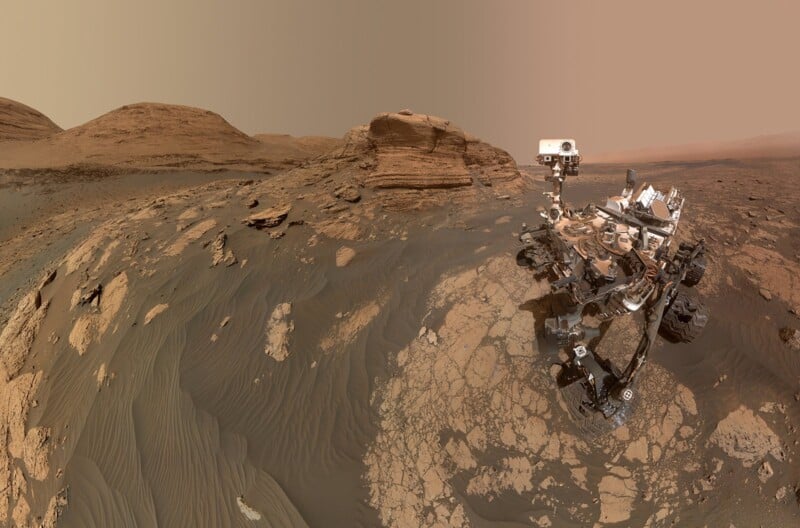

Before diving into the new photo, it is worth stepping back and paying homage to another of Ellison’s postcards. In November 2021, the Curiosity rover delivered a postcard to Earth using its navigation camera. That image is also a composite panorama, combining panorama images captured at two times of the day.

When Ellison and the Curiosity team captured that postcard in 2021, he told himself that he needed to do it again the next chance he got. When the software update was scheduled for this year, Ellison approached Curiosity’s project scientist lead, Ashwin Vasavada, and instantly got the go-ahead. Ellison and Vasavada had “previously conspired” on the 2021 postcard.

This postcard really “caught people’s imagination,” Ellison explains, which was the team’s primary goal. He knew the second opportunity would be similar regarding overall location and lighting, so he was more confident and better prepared ahead of time.

Capitalizing on a Unique Opportunity

The Curiosity team has limited time each day on Mars to work and there are not often chances to capture images like the new panorama. While beautiful, the photo doesn’t offer clear-cut scientific benefits.

However, following a significant software upgrade, Curiosity’s team needed to spend time each day to bring the rover’s instruments back online. It is more complex than flipping a switch and returning to scientific operations.

The update has been in development for years, bringing new driving capabilities to the venerable rover. Before it puts the proverbial pedal to the metal and charts new tracks on Mars, the team must go through the motions, necessitating downtime.

One of the first instruments back online is Curiosity’s navigation camera, meaning that Ellison and his team of engineers could exercise a bit of much-welcome freedom and artistic exploration, even if physical exploration was off the table.

“We’re usually very constrained — either time-constrained or power-constrained — packing things into any given days’ worth of activities. We just had this unique opportunity. We had just upgraded the rover’s flight software, which isn’t something we often do. The last one was many years ago, and it was a major effort over many years,” Ellison explains.

“We were coming out of that flight software transition, we had a three-day plan that went over a weekend where we were happy to do some things with the rover, like move the camera mast and take pictures, but not do other things because we haven’t quite finished reinstalling everything. We had this window, and Ashwin Vasavada and I had previously conspired to do something like this back in November of 2021, and that time it was his idea to take an uncompressed postcard and my idea to take it twice. I brought it up this time and told Ashwin, ‘It is going to be a quiet weekend, and it is winter on Mars, mind if I try doing it again?’ He said, ‘Absolutely, go for it.’ We found two slots, one in the afternoon and one in the morning, to take these pair of postcards,” he tells PetaPixel.

When Ellison mentions winter on Mars where Curiosity is working, that is very important. During winter, there is significantly less dust in the atmosphere on Mars, and conditions are considerably more favorable for capturing beautiful, detailed photos.

Despite the Great Panorama, the Navigation Cameras are Limited

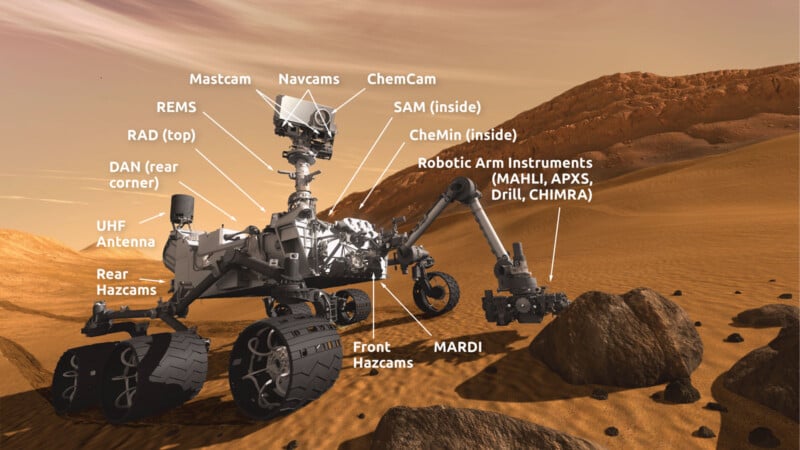

“The navigation cameras, which took these images, they are the lowest on the food chain in terms of what the rover can do in terms of imaging, but because they are essentially ours, they’re a facility that we can use at will, rather than a scientific instrument that we need a specific purpose to use, we had that freedom and opportunity, so we went for it,” Ellison says.

Curiosity has two types of cameras: engineering and scientific. Scientific cameras, like Mastcam, are very high-performance. The scientific cameras are high-resolution and capture full-color images.

On the other hand, the navigation camera and other engineering cameras have 1-megapixel image monochrome image sensors, a far cry from Perseverance’s 20-megapixel full-color navigation cameras. The navigation camera has a 45-degree field of view.

“We typically use the navigation camera to get the lay of the land. Whenever we drive the rover, we pull up and take a complete 360-degree image of the landscape once we stop,” Ellison explains. “We also use them for things like dust devil movies, cloud movies, looking for weather phenomena, because they have that nice wide field of view for looking those potential features you might see in the sky. They’re primarily there for engineering, but we do a bit of science with them. They’re more at our disposal at the JPL engineering side than the science cameras.”

Providing Color to Monochrome Sensor

In 2021 with Curiosity’s other similar postcard, Ellison processed monochrome image sensor data into a full-color image. This is common within the context of NASA images, as many of its instruments have monochrome image sensors.

Converting black and white images into color requires digital manipulation, which is technically “false color” but not always far removed from reality.

Before moving from the monochrome world into one rich with color, Ellison needs to stitch the images together. The Curiosity team had the rover capture the same ten-frame mosaic at two different times of the day. Once these lossless images — another oddity, as Curiosity’s onboard compression software usually reduces the size of images before sending them to a Mars orbiter to be relayed back to Earth — arrived at JPL, Ellison began stitching them together and correcting for parallax error.

The mosaic is five frames wide and two frames tall, which Ellison tells PetaPixel is an additional frame wider than the 2021 postcard, allowing him to create a full 4K resolution wallpaper.

“After stitching the two black-and-white panoramas, I literally go into Photoshop and assign the morning image to be a blue channel, assign the afternoon image to a red channel, and then using channel mixer, make green 50 percent of each, and that gets you 90 percent of the way to what you say,” Ellison says.

After this channel mixing, there is a bit of tweaking to ensure each image is lined up, and Ellison performed a bit of additional adjustment, such as curves and levels. He also extended the gradient in the sky to ensure the postcard fit a typical desktop monitor.

“That was the intent, to create something people can have on desktops, so the sky is real at the bottom and then extended to the top of the image from there. So yeah, it’s just a blue channel for the morning, a red channel for the afternoon, half of each for the green channel, some levels, some curves, and some denoising here and there,” says Ellison.

In the image, the Sun is rising to the east (right) in the morning and setting to the west (left) in the afternoon. The landscape in the right half of the panorama is illuminated by the afternoon sun, which Ellison assigned to the red channel. In contrast, the landscape to the left is illuminated by the morning sun over the eastern horizon, which is the blue channel. The two colors stand out on the rover itself as well.

“It’s like using stage lighting, like putting a bright blue spot on one side of the stage and a bright orange spot on the other side of the stage. We let the Sun move, taking one image in the morning and another in the afternoon,” Ellison says.

PetaPixel describes the Martian landscape in the postcard as simultaneously alien and familiar.

“That’s what we were going for,” Ellison exclaims. “When we did it two years ago, I hoped it would look like this if we took two images at different times of the day. I had an idea it’d look like this. I liked the result then, so with some confidence, I proposed the idea again this time.”

Ellison also notes that this is different from the standard process the team uses at JPL to process images from Curiosity. The team has unique sequencing processes and algorithms to create color-accurate photos. However, when crafting something that is intended to be a “pretty postcard,” some of those standard constraints are lifted, allowing Ellison to flex his artistic muscles.

The ‘Red Planet’ is Brutally Cold

“We’re used to seeing Mars as the ‘Red Planet,’ right? These aren’t real colors. They’re just an artistic interpretation, you could call it a ‘photometric response map’ of the ground if you want. A study was done of what school kids knew about basic space and planetary science 20 years ago. One of the questions was about conditions on Mars, and the kids’ top answer was that it’s hot, probably because we associate ‘red’ with ‘hot,'” Ellison remarks.

However, the opposite is true — Mars is excruciatingly cold. “For the morning image, the bluer colors in this mosaic, we had to heat the cameras up in the morning to get them to -55 degrees centigrade (-67 degrees Fahrenheit) because that’s the coldest we let ourselves use the cameras. That’s how cold it is in the morning. That sense of this planet that we normally see in very warm colors — browns, ochers, and rust — that feels like a nice warm walk in the desert somewhere, but it’s freezing cold. The warm and cold colors we used were chosen carefully,” Ellison explains.

“When planning activities for the rover, we put heating in to warm up various actuators because it’s so cold in the morning. We’re pretty much in the depths of winter with the rover right now. We spend a not insignificant amount of our energy to warm the rover up to be warm enough to be used at all. The colors are there to try and tell that story,” Ellison continues.

As a brief aside, Ellison says something PetaPixel hadn’t heard before about the temperature on Mars. During the height of the Martian summer, the surface temperature is above freezing.

“Apart from the fact it has no atmosphere, so you’d immediately asphyxiate, in terms of temperature, the ground temperature would be room temperature, but the atmosphere is so thin that you could walk around in sandals and a parka. Your head would be so cold. It’s bizarre,” adds Ellison.

The Curiosity team schedules heating based on when they know the team will start using instruments, just to get them warm enough to be ready to use.

Careful Planning Underpins Curiosity’s Work

While the team at JPL would love to have a joystick that they could use to control the rover and move it around at will, the sheer distance from Earth to Mars — nearly 200 million miles – makes that impossible.

During the interview, Ellison checked an app and said that the communication time was about 17 and a half minutes. It changes depending upon the orbital and rotational patterns of Earth and Mars. That means that when someone at JPL wants Curiosity to do anything, that radio signal takes nearly 20 minutes to reach Curiosity. That’s a bad case of input lag for the gamers out there.

“We essentially email the rover a giant to-do list when it wakes up in the morning, and that takes us about half an hour,” Ellison explains, adding that he uses “regular time” when talking about Curiosity because despite the Martian day (sol) being longer than a day on Earth, the team converts Martian time to fit a 24-hour day for simplicity’s sake. A “second” to Curiosity’s schedule is longer than a real second. “We cheat it so that time feels familiar,” Ellison says.

A day in the life of Curiosity comprises waking up and receiving instructions, which it then carries out until the next communications pass with one of NASA’s Mars orbiters. Curiosity will send its data then and receive new instructions, often for scientific imaging and perhaps a bit of moving. The rover moves 10 or 20 meters in a day, or up to 40 meters on a good day. By this point, it is around noon on Mars, and the process starts over again.

Ellison says that there is sometimes a scientific reason to go slightly off schedule and disrupt the standard operating procedure. He mentions specific examples like observing twilight clouds. Scientists can use the shadows on the clouds to learn about their height and can even learn something about the crystallized structures within the clouds from Curiosity’s photos.

Ellison’s ‘Terrestrial’ Photography Overlaps with his Work on Curiosity

“I take my terrestrial photography somewhat seriously as well,” Ellison explains. “I’ve got a Canon EOS RP. I’ve just come back to Canon full-frame, and I look at the size of one of the RAW images that come off that, and I just giggle. That’s an entire day of images for the rover.”

Alongside his work controlling Curiosity’s cameras, Ellison has “always loved photography.”

“My dad was a big photographer. He always had a really nice camera and a bunch of decent lenses,” he explains.

“I enjoyed landscape and wildlife photography when I lived in the UK. When I moved to southern California, suddenly I had the Mojave desert in my backyard. That changes the story in landscape photography, and it was so incredibly alien to me, but also weirdly familiar in terms of these desert-type landscapes we see on Mars,” Ellison continues.

There are many incredible and diverse landscapes within six hours of JPL, Trona Pinnacles, the Mojave, Death Valley, Yosemite, and much more. “We are just spoiled rotten with places to go to scratch a landscape photography itch over here,” Ellison says. “I’ve spent many an hour doing landscape photography in the Mojave.”

“Certain scenes will catch your eye here on Earth, and in your head, you tell yourself, ‘I’ve got a nice camera and a nice lens, but I don’t know how to put this into the camera,'” Ellison explains, adding that he likes to take these moments and just enjoy them with his eyes for a minute.

“With the rover, we have no choice. These cameras are our eyeballs, so we always have to try to do the best we can. Most of the time, it’s very formulaic and driven by the need of what we must do to prepare for the next day. However, from that purposeful need-driven photography we do with the rover, something will catch your eye, and you wish you had the time to do that properly. All credit to our project scientists, who often feel the same way,” Ellison says.

While the team is often constrained in what it can shoot, and they are on a tight schedule and a restricted energy budget with the rover, there are opportunities to capture beautiful images to share Curiosity’s surroundings with the world and create exciting content.

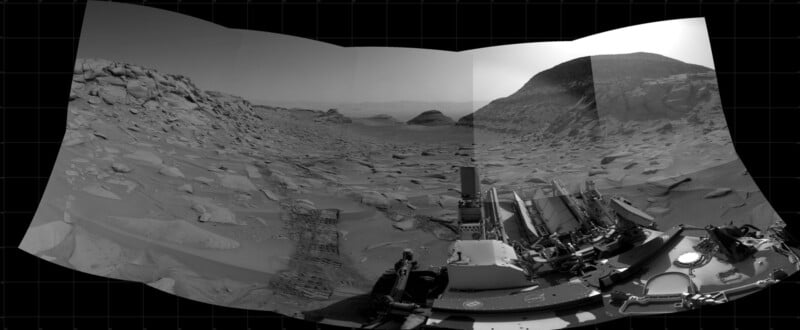

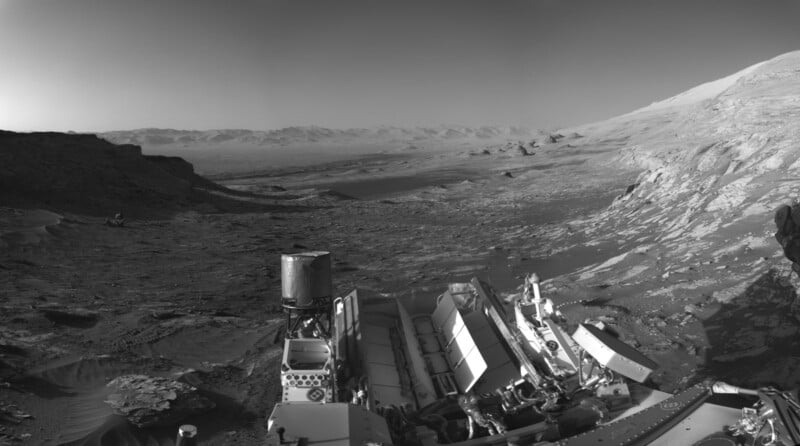

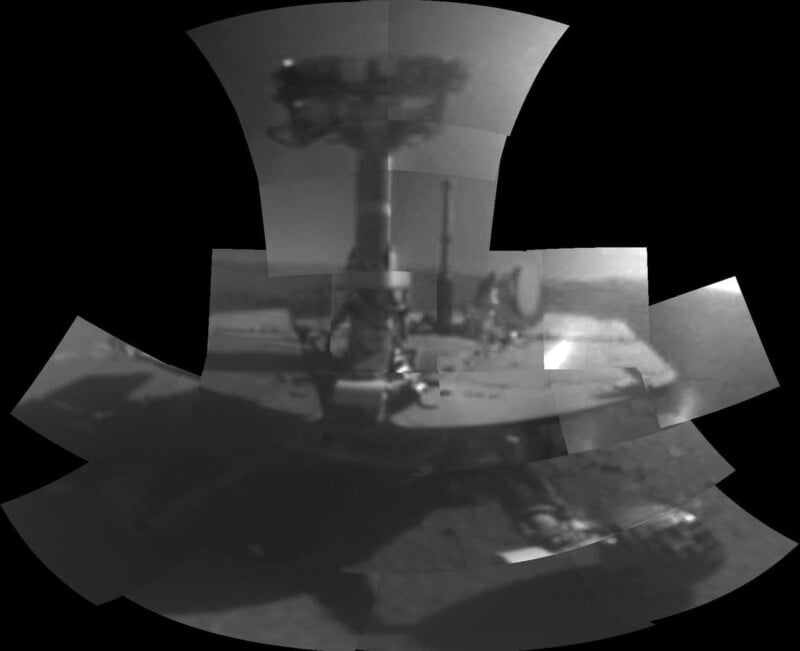

Alongside the release of the colorful new postcard, Ellison also wanted the team to include the original black and white shots he captured. That wasn’t by accident.

“It would be vulgar of me to say it’s an Ansel Adams kind of thing, but there is something to the art of black and white photography and enjoying a landscape for what it is with just that to hand. I love what the science team can do with their color cameras, but I love what we can do with our black and white cameras as well,” Ellison says.

Déjà vu in the Desert

During the significant time Ellison spends in the field on Earth capturing landscape photos, especially in the desert, he sometimes comes across landscapes that feel strikingly familiar to those he has seen on Mars.

Ellison has spoken at the Death Valley Dark Sky Festival on numerous occasions, including the last couple of years. In preparation for his presentation, he took his camera and an old lens with a similar field of view to Curiosity’s engineering cameras and visited famous Death Valley haunts. He captured photos in the approximate style of Curiosity’s navigation camera.

“There’s a small hill in the middle of Death Valley called Mars Hill. It got that name from artists decades ago that recognized it’s so much like the Mars terrain we saw with the Viking lander in the 1970s. They’d go there to paint a Martian landscape because it looks so Martian. It speaks to the same geological processes happening on Mars that have happened here. Mars’ primary hobby is turning large rocks into small rocks. That’s what it’s been doing for billions of years,” Ellison explains.

“I looked across Death Valley, and I’m looking about 15 miles across the valley, and I see this alluvial fan, a fan of debris from a river channel cutting through the mountains. We see the same thing on Mars,” Ellison says. These landforms on Earth are much like the ones on Mars. It is incredible how Ellison’s photography goes full circle for about 200 million miles.

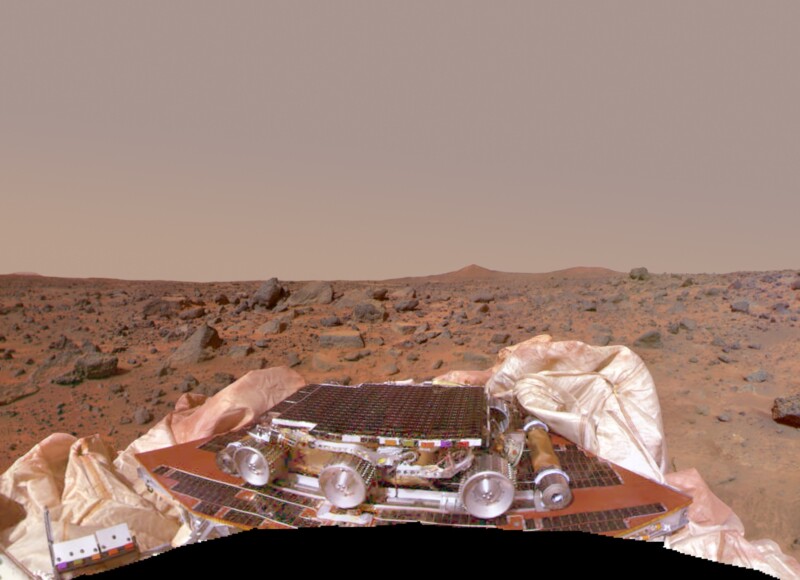

From Citizen Science to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory

“The ‘Doug origin backstory’ very loosely is that I work at JPL now because I was processing images from the Spirit and Opportunity rovers back in 2004,” Ellison says. The images from these early rovers were released online for everyone to download, play with, and feel like they’re part of the big adventure NASA and JPL undertook.

Ellison didn’t go straight from processing images as a civilian to leading Curiosity’s imaging team. He came to the United States and began working on the visualization team, where he produced multimedia content and was involved in projects such as Curiosity’s “Seven Minutes of Terror” and the Deep Space Network Now website.

From there, Ellison transitioned into doing more research and tech development work, including with the Microsoft HoloLens.

In 2016, he became involved in mission operations, operating the engineering cameras on Curiosity.

“The moment I was certified to operate cameras on Curiosity, I spoke to the Opportunity team, and they let me play with Opportunity for the last 18 months or so,” Ellison says. His work during Opportunity’s final stages led to appearing in the Amazon Prime documentary Good Night Oppy.

While he has been with Curiosity ever since, Ellison’s work with Opportunity in its final months left a huge mark on “Oppy’s” history. Ellison engineered the first and only selfie captured by Opportunity.

It is not just Ellison that has been involved with processing NASA images as a civilian, Ellison tells PetaPixel that the prolific JunoCam image processor, Kevin M. Gill, who has processed nearly a thousand images from JunoCam, is part of Ellison’s engineering camera team. Gill processes JunoCam’s images of Jupiter for fun on his own time.

A Spirit of Generosity Runs Throughout NASA and JPL

Throughout PetaPixel’s conversation with Ellison, what became clear time and again is that he and the rest of the Curiosity team are incredibly passionate about what they do every day.

The team is ecstatic about the chance to be on the forefront of human exploration, and it is a privilege that isn’t lost on anyone. Each day, they work together to further push the boundary of human exploration.

Much of NASA’s overall mission is to share the knowledge it gains with everyone. The public can follow along in ways that very few other scientific endeavors allow, and it is gratifying for Ellison and others. They pay close attention to what people do with the images they share. As Ellison himself can attest, sometimes the work people do because they are passionate about space, and NASA can pave the way to working for NASA itself.

“We try to put all these tools and images out there to allow people to feel as close to being a part of this mission as possible because it’s their mission too. I feel very strongly that we should, now and again, take the time to do something specifically and intentionally to engage with the public,” Ellison says.

“We’re very fortunate, and you can see with the new postcard mosaic, we’re in a beautiful and dramatic landscape. We’re genuinely lucky that the science team has good reason to come somewhere that’s so amazing to look at,” adds Ellison.

The postcard is a form of gratitude for people’s enormous enthusiasm and passion for the work the Curiosity team does.

“My engineering camera team, the whole of the Curiosity team, we know we’re incredibly lucky to be involved in a project that’s this exciting. You go home with a nice warm fuzzy feeling. You’re doing something that matters and part of a project doing amazing things. You’re part of an amazing team that works together, and you get to share it. We are making at the forefront of human discovery, we’re making progress, and we’re making discoveries,” Ellison says.

Ellison mentions that perhaps one day he’ll turn an engineering camera behind a Mars rover and see boot prints on the ground. “I can’t wait to see them,” he says.

When he does, such an incredible achievement will have been made possible in large part by the work that Ellison and everyone else who has worked on Mars exploration missions has done.

Image credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech