Street Photography Is Not a Crime. Let’s Keep it That Way.

![]()

The New York Daily News recently published an opinion piece by a writer named Jean Son titled “When your photograph harms me: New York should look to curb unconsensual photography of women” and I would like to address it here.

The author says that “there’s only been a few times in my life when New York let me down, and they all happened in broad daylight in some of our most recognizable public places.”

Wow. Something dramatic must have happened, right?

The first example that Jean Son relates is that when she was 17 she was sitting in Bryant Park when “an older man walked by with two cameras and discreetly aimed one at me. I immediately called 911.”

…Really? Is calling 911 for someone taking a picture of you the appropriate action in this situation? Seems like a bit of an overreaction.

She then goes on to describe the rest of the interaction: “a police officer made him destroy one of his rolls. Because he refused to say which camera he’d used, to this day I’m not sure if the photo lives on somewhere. What I do remember is the violation and fear that I felt as a strange man captured something of mine, my image, without my permission. He got to walk away.”

He got to walk away? Yes, he got to walk away — he did nothing illegal or wrong. What is Jean Son’s expectation here? That the photographer be thrown in jail for doing something that’s perfectly legal? Not to mention that the police officer had no right to make the photographer destroy his film.

Here’s how Jean Son describes her next encounter with a street photographer:

“I was walking down 57th St. A man with a long-zoom camera lens pointed it at me and took a rapid series of photographs. When I confronted him, he said it was a ‘free country.’ As he tried to get away, I grabbed him and called 911.”

The photographer was right — at least in the sense that photographers are free to include anyone out in public in a photograph as long as it’s not for commercial use.

And the interaction unfolds:

“Four Business Improvement District workers approached us and began commiserating with him as I, the victim, stood gripping my perp by his bag. One said I was ‘making a scene’ while another joked that ‘maybe he just liked the pictures.'”

This is where the author is really reaching in my opinion. She starts using police language to describe the interaction. She’s “the victim”, while the photographer is “my perp”.

I mean… What was she the victim of? A photographer who pointed a camera at her and pressed the shutter button. And that somehow makes the photographer a “perp”, as in a perpetrator of a crime.

![]()

Not only that but she grabbed the photographer by his bag and wouldn’t let him go. If anyone is guilty of assault in this situation, it’s Jean Son.

I can honestly sympathize with Jean Son that she was made to feel uncomfortable. But I can’t help but find it amusing that she chose to include how the witnesses of the whole thing were joking around and thought that she was making a scene out of nothing— because that’s sure what it sounds like she was doing.

Here’s how the interaction ends:

“The cop who arrived 40 minutes later discovered that my assaulter had taken dozens of full-body burst shots of me, which he was told to delete. I watched him walk away in his tan cap and polo shirt, with tears streaming down my face and cramps in my hand. I wondered whether I should have worn a different dress to work that day. I wondered whether he’d think twice before pointing his lens at another young woman, or whether, more likely, he’d become even more emboldened, knowing that at worst he could walk away.”

OK, so the fact that someone pointed a camera at Jean Son and took a picture caused her to not only 1) cry, but also 2), grab the photographer’s camera strap and hold on so long that she got cramps in her hand.

For whatever it’s worth, I don’t think an interaction as negative as this would embolden any photographer to go out and shoot more. I think it would make the photographer want to take a break so as to not have to deal with someone so unreasonable as this, at least for a short while.

There’s one last encounter that Jean Son claims to have experienced, which she describes as such:

“In the wake of #MeToo, I often found myself thinking about this last incident. I was proud that I stood up for myself, but I promised myself that if it ever happened again, I’d do something ‘real’ about it. Then, last December, I was in Chelsea with my mother, talking and laughing. A young man lifted his camera inches from my face.

‘It’s not illegal,’ he said. ‘It’s art. Get away from me.’ He deleted my photo and walked away.”

Based on the previous interactions this person has had with people taking her photo in public places, it sounds like the photographer’s best course of action was to walk away, so it sounds like he made the right decision.

Jean Son acknowledges:

“He’s right: It’s not illegal to take photos of people in public.”

But she goes on to say:

“But women are victimized by this lack of legal protection of our images.”

OK, well I’m all ears if we’re talking about women being victimized.

She then goes on to cite three examples of cases where men took inappropriate photos of women in public and violated their privacy (and I agree that their privacy was violated in these cases). Here are the headlines from the cases she cites:

1. Upskirt Photos Don’t Violate A Woman’s Privacy, Rules D.C. Judge

2. Trailing Women With a Camera Was Legal, Appeals Court Rules

3. Texas court upholds right to take ‘upskirt’ pictures

I will be the first to admit that these court cases are egregious and their rulings are morally wrong and I disagree with them. Anything resembling upskirt photos violates privacy and should absolutely be illegal.

However, why are we lumping the actions of some random perverts in with street photography as a whole? Taking “upskirt” photos is not street photography at all. It is absolutely NOT the same thing and should not be treated as such.

Jean Son acknowledges that upskirt photography is already illegal where she lives in New York:

“Taking upskirt photos is a felony in New York. But while it’s great that taking photos of specific body parts is considered a crime, any act of photographing someone in a degrading, violative way without her consent in public is wrong and the law should reflect that.”

If we break this down we can basically objectively say that pointing a camera up a woman’s skirt constitutes a felony because it’s taking a photo of specific body parts of a woman. But if we’re talking about photographing someone “in a degrading, violative way”, that becomes entirely subjective.

So Jean Son gives three examples of herself being photographed in public that are dissimilar to cases she cites of women being photographed in sexual ways. None of the examples she cites from her personal experience were sexually exploitative, so the only conclusion I can really make about what she wants to make illegal is any kind of photographing of women in public, even if it’s not sexual in any way.

She says that “we should set an example for the country and protect women against all nonconsensual, exploitative photography and videography.”

Jean Son says that she has been “working with Councilman Jimmy Van Bramer on legislation convening an image privacy task force that will address photography as a vehicle of gender-based violence in public places. If this bill is passed, the next perp will have to think twice before assaulting another woman on our streets in the name of “art,” or a “free country.”

Again, she labels any photographer who dares include a woman in public in a photograph a “perp”, to imply insidious motives and criminal activity when in reality the only “crime” that was committed was taking a photo.

On Twitter, the New York Daily News posted their article and a photographer named Eric Henne commented:

![]()

And I have to agree — these photographers would not have been able to do all the amazing work they did and we would not be able to enjoy it if we ban street photography like Jean Son is proposing we do.

And here’s where it gets strange, when Jean Son adds to the conversation:

![]()

For one, she claims that she wants “predators” who shove their cameras in a woman’s face to be penalized. But in her first two interactions with street photographers, she doesn’t say that the photographers got up close to her. In fact, in the second example she gives, the photographer was far away and using a long zoom lens. Her criteria for what kind of photography she wants to criminalize is totally inconsistent.

And it really can’t get any more inconsistent than wanting to essentially ban street photography and make it illegal while at the same time claiming Garry Winogrand as one of your favorite artists. It makes zero sense.

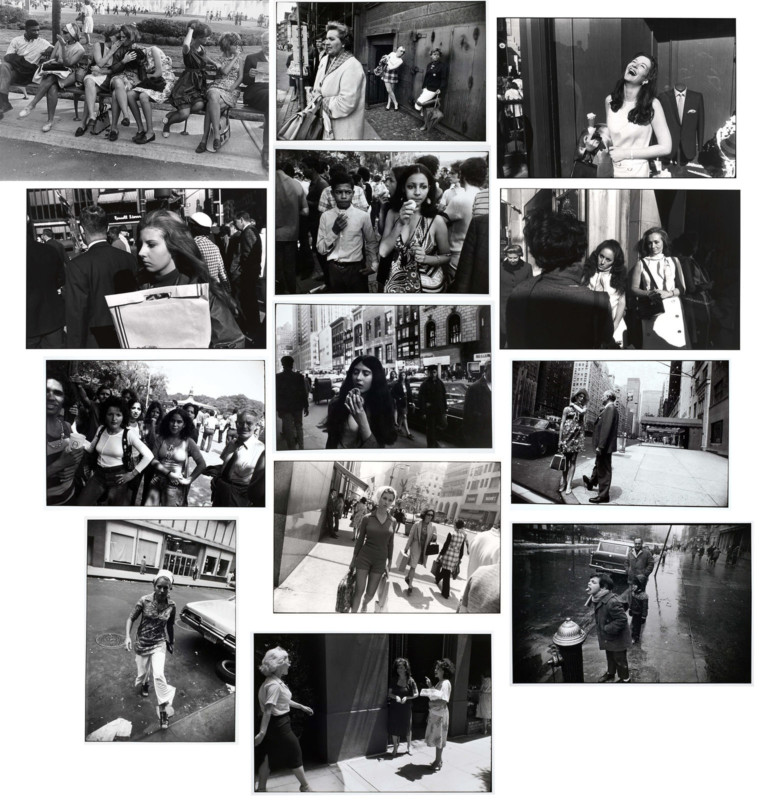

Here are some of the photos Garry Winogrand took throughout his photography career:

As you can see, Garry Winogrand took lots of photos of women. And men, and people of all colors and ages. And as far as I know, all of his personal street photography work was candid.

And in fact, Garry Winogrand caused a lot of controversy when he released his book Women are Beautiful in 1975. I don’t even think it’s his strongest work; I just mention it because what Garry Winogrand did to make his photography is exactly what Jean Son wants to criminalize.

But guess what? All those people who Winogrand photographed went unscathed after he photographed them. Because photography is not violence. It is not a violent act and to label it as such is extremely dishonest.

And by the way, what about women street photographers — where are they in this discussion? Assuming that all street photographers are men is erasing them. And how about when a woman street photographer takes photos of men — should that be a crime too?

I believe street photography benefits society. There’s a reason why museums all over the globe display it.

To ban street photography in public places would be to eliminate the joy that so many get out of it and we would lose documentation of places in time. Banning candid photography in public places is also a slippery slope that leads us down a path to where photojournalism would likely be attacked as well.

Here’s a rational, mature, adult way of dealing with a situation of you’ve been photographed by a street photographer and you don’t like it: politely ask the photographer if they took a picture of you, and if so, if they would delete it. And if they refuse, that’s their right and you go about your day.

If being photographed while out in public causes you such distress that you lobby to convene a task force to ban it, I don’t think photography is the problem. I think you have some underlying personal issues that you need to work through and confront as an individual, rather than making this into a systemic problem that doesn’t actually exist.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.

About the author: Brandon Ballweg is a photographer from Kansas City. He is the founder of ComposeClick. This article was also published here.