My 10 Year Search for the Perfect Camera Brought Me Back to APS-C

![]()

In 2015, I fully committed to switching from my Nikon DSLR system to a Sony mirrorless system starting with the Sony a7 II. Up until that point, I had always held on to my Nikon D700 and D800 as my workhorse cameras for weddings and commercial shoots but experimented with Olympus, Sony, and Panasonic for my travel photography.

A foreword. I’m not one to fixate on gear more than what purpose it serves. I prefer to upgrade only when I need specific specs or if it will improve what I deliver to clients, so to help you understand the significance of this switch and my thought process, I want to take you back about a decade or so to when I adopted a two system setup.

Does The Size Of My Sensor Make You Comfortable?

For my first around the world trip in 2010, I left behind my Nikon D700 and instead carried a tiny Panasonic GF-1 Micro 4/3 sensor camera, the 14-42mm kit lens, and a 20mm f/1.7 pancake lens. My trusty Manfrotto also stayed at home and in its place, a $15 tripod that would blow over with a strong wind. Being stable all the time wasn’t one of its strong points, but it collapsed down to about 10 inches and expanded to 54 inches.

Everything fit into a small ragged looking canvas messenger bag that I outfitted with a camera insert I sewed myself. It was as inconspicuous as I’ve ever been as a photographer and so liberating.

![]()

From that trip, I learned that portability and the content of what I shot were more important than even the image quality and features on the camera. The first travel video I made from the photographs on that trip went viral and paid for the entire year’s worth of travel.

With the compact GF-1 and a simple tripod I could set up in about 10 seconds, I was able to get many shots and sequences that I would have missed with my larger Nikon setup. I’m certain of this because there were times places where “professional” gear was not allowed, but none of the security guards blinked at eye at me.

Some of my all-time favorite shots were done on this little thing.

I haven’t touched the camera for years now, but this was one of my all-time favorite setups because of its compact size and simplicity. To be honest, I can’t even remember the megapixel count or if I shot RAW on the GF-1. Probably not. I just remembered that I had my messenger bag with me everywhere since it was small and so my camera was never more than a quick reach away right by my side.

Many people rave about how fast a camera is ready to shoot when you turn it on. I also consider how long it takes you to get it out of your bag.

Switching From Nikon To Sony

My first experience with Sony and an APS-C mirrorless sensor was the Sony NEX-6, a predecessor to the still popular, a6000. It was my way of stepping up from the GF-1 to something similarly compact but with a bigger sensor. I shot many travel films and memorable landscape shots on it with the 16mm f/2.8 pancake lens and wide-angle attachment and I adapted vintage Voigtlander and CCTV lenses to get many keeper portraits.

![]()

![]()

I never once, during that time, thought anything less of a smaller sensor nor did I think of not be able to get shallow enough depth of field with the available lenses, as you can see from the portrait above.

Then the Sony a7 II came out, improving on many of the flaws found in the much-touted Sony a7, the first mirrorless full-frame camera with an interchangeable lens system. Finally, I could get the same quality as my full-frame DSLR in a more compact form and I fell for it hook, line and sinker.

I shot with this for the next few years alongside the a7S II for my video work, and only upgraded when the a7 III came out.

With the Sony and its live preview, my exposure was spot on for every shot, but I did slow down a bit because I felt compelled to adjust almost every shot. I also started to shoot more with the LCD instead of through the viewfinder. It was a completely new shooting style compared to shooting on my Nikon and great for my product work.

![]()

For weddings though, I was worried I would miss the shot if I kept focusing more on fine-tuning exposure rather than just shooting while occasionally flicking my eye over to the meter. Does anyone else still remember the days when we actually metered?

I hung on to the D700 and D800 for another couple of years because of this, but eventually took a chance and shot one of my weddings on the Sony.

Any fears I had were immediately dispelled as I ended up with an even higher percentage of usable shots that were 99% perfectly focused. I even got so comfortable that I shot an entire wedding with just one lens at one point.

For the first time in a long time, I was able to consolidate my professional photography and my travel videography into one system. In a way, I felt at peace not having to compromise image quality for portability and choosing one system over another when I was on the road, but this was where things also slowly started to break down again.

The Mirrorless Size Trap

Mirrorless systems’ promise of smaller cameras and lenses were only half true. The cameras, without the mirror reflex system, were indeed smaller than its DSLR counterparts, but you can’t break the physics of optics when it comes to lens size on full-frame sensors.

To get a certain image quality and amount of light into a lens, there are physical limitations to how small you can go.

If you compare all the professional workhorse lenses like the 17-35mm f/2.8, 24-70mm f/2.8, 70-200mm f/2.8, the sizes were more or less the same regardless of whether they were DSLR or mirrorless.

So much for a smaller system. The body was smaller than my DSLR, but the lenses were more or less the same size. Some of the mirrorless prime lenses were even bigger and more expensive than their DSLR counterparts. The Sony 55mm f/1.8 cost about 7 times its equivalent Nikon or Canon Nifty 50 counterparts.

With that said, with the Sony a7 II, a7S II, and the incredible a7 III all having incredible image quality, video features, and low light capabilities, I felt like I couldn’t go back down to the smaller APS-C cameras.

Being Weighed Down

I eventually sold all my different messenger photography bag and switched to bigger backpacks so I could carry all the bigger lenses and bigger tripod with me. Before I knew it, half of what I took on my travels was my gear alone.

Somehow I seemed to have forgotten why I left my larger Nikon D700 at home in the first place when I was started traveling.

Trip after trip, I searched for ways to downsize. Smaller backpack, medium size tripod, no tripod, smaller lenses, fewer lenses. It was never-ending and I didn’t even realize that the gear was dragging me down and changing the way I shot for the worst.

I stopped owning a 70-200mm lens and would sometimes leave behind the 24-70mm f/2.8 GM when I was on the road. When I felt too bogged down, I would leave behind all my Sony lenses and go for smaller adapted lenses shooting completely with manual focus.

There were even times when I would bring the lenses, but just left most of it back in my room or bag and went out with just one lens, only to wish I had a different lens with me when something caught my eye. I made it work, but way more often than not, the thought of carrying all that gear made me not want to shoot.

Letting Go Of Full Frame

Like many photographers, I regarded full-frame as the standard for photography. More than anything, I was used to the look I got off my full-frame sensors and my workhorse lenses. I understood all the nuances of the arguments between full-frame and APS-C or m4/3 sensors. I knew the disadvantages and limitations of the smaller sensor systems.

None of it really limited the most important thing in photography – taking the picture. Yet, irrationally, I refused to consider going back down in sensor size.

Outside the endless YouTube and web reviews comparing the latest and greatest specs, we know that you can create beautiful photography with just about any camera, even the ones from a decade ago (but promoting that doesn’t sell new cameras). Camera technology has rapidly advanced in the last decade, my 10-year-old GF-1 can still take photos today like it did when I first held it.

There’s now enough native lens and adapted lens selections to allow you to create, uncompromisingly at the highest level, with any system.

New tech is great, but amazing imagery has been made for a very long time before the digital spec wars of the last decade.

Ironically, none of this was news to me. I shot for publications with a 2.74 megapixel Nikon D1H back in the day, some of my best images were on a micro 4/3 sensor and I’ve sold photos taken on a *gasp* god forbid, 1” sensor found on the Sony RX100 IV point and shoot.

Holding on to full-frame, when the size and weight factor was holding me back, was pure stubbornness backed only by the need to have the perceived “best”. I was finally ready to let go of full-frame and go lighter again.

Switching From Sony To Fujifilm

My switch to Fujifilm was delayed in part because as a hybrid photo/video shooter, I was hoping the Sony a7S III would be the camera to end all cameras. Something along the line of 4:2:2 10 bit 4K 60 fps along with a 24- or 36-megapixel sensor so I could do everything with one camera.

I am so glad Sony stuck with the 12-megapixel sensor to make my decision easier.

From a photography standpoint, I had long been drawn to the beautiful Fujifilm cameras that are so well-loved by street photographers and photography purists. The retro-style bodies and dials much more resembled shooting with 35mm film cameras. And everyone was raving about the straight out of camera colors.

![]()

![]()

Because all their cameras, apart from the GFX medium format series, were cropped sensors, most of the lenses were smaller and lighter too. I was more than tempted.

Somewhere at the beginning of 2020, rumors were floating of Fujifilm wanting to cater to a wider audience that included video shooters. Those rumors eventually became the Fuji X-T4 that would end up checking every box for me.

But even before that, I saw in the Fuji X100V a camera that excited me about shooting again.

Like my Sony RX1, which fixed a sharp 35mm f/2.0 Zeiss lens onto a compact full-frame body unheard of at the time, this was a camera built to be carried everywhere to capture everyday life. The x100V would be my first step towards a full transition to Fujifilm.

![]()

![]()

The X100V’s One Focal Length

What I love most about the X100 V is the compactness. Not only is it small with a lens that barely protrudes from the body, but it’s also built really well, so I could throw it into my fanny pack or attach to a Spider Black Widow Holster without worrying about damaging it.

![]()

It’s got a built-in ND filter to allow me to easily stop down to f/2.0 in any lighting condition and the leaf shutter is so silent, I initially wasn’t sure I had taken the shot after pressing down on the shutter.

Inside the gorgeous rangefinder-style body is the same flagship 26.2-megapixel X-Trans 4 sensor like in the X-T4 and a 23mm f/2.0 lens designed specifically for the sensor. It’s sharper than the Fujifilm 23mm f/2.0 WR lens and half the size.

After shooting for a month with it, I didn’t feel limited by the fixed focal length at all. The 35mm equivalent of 35mm was already my favorite focal length on my Sony a7 III, so I was very comfortable getting in closer for portraits and stepping back for wider shots.

With the Classic Chrome Simulation, I’ve actually been pleased enough to send the JPEG straight from camera to my phone and post without any color correction. And it’s so easy to use.

The range between light and shadow was pretty difficult in the scene above, but I think the X100V captured it pretty well straight out of camera. My girlfriend, who has just a bit of photography experience, just picked up the camera and snapped this shot while I was getting ready to jump into the water to chase after a turtle.

The second image was edited with some very minor adjustments, specifically in bringing back some details in the highlights, but otherwise, I would have been happy with the straight out of camera jpeg.

What About Shallow Depth Of Field?

At the same equivalent focal length, the same aperture value looks different between a full-frame sensor and a mirrorless one. It’s easier to find zoom lenses that will give you shallower depth of field (though I’m sure some will still want to debate this) on a full-frame camera.

I, too, was worried that I was giving something up in this area. Fujifilm has a sharp 16-55mm f/2.8 lens that’s supposed to be the equivalent of the workhorse 24-70mm f/2.8 lens that most photographers would be familiar with. The optics are amazing, but f/2.8 on the cropped Fujifilm sensor has the equivalent depth of field as f/4 on a full-frame sensor.

The same goes with their 55-140mm f/2.8 (vs 80-200mm f/2.8 FF) and 10-24mm f/4 (vs 16-35mm f/4 FF). The bottom line is that I couldn’t get the same shallow depth on field on native ZOOM lenses unless I adapted larger and heavier full-frame lenses from another brand like Canon with a focal length booster like this Viltrox .71x Speedbooster Canon EF to Fuji X mount adapter.

I had to accept this and let it go as well. But it would be naive to think you can’t get really shallow depth of field on a cropped sensor – especially with prime lenses.

The Fujifilm 35mm f/1.4 will still give you a buttery out of focus background. The Fujifilm 56mm f/1.2 even more so. And there’s even the Mitakon 35mm f/0.95 for those who really want practically everything out of focus.

![]()

In the real world, I found myself stopping down to f/2.0 and f/2.8 more often than I realized, even when I could shoot wide open at f/1.4. Why? Because sometimes f/1.4 is too soft or the field of focus is way too narrow on full-frame.

Getting shallow depth of field on an APS-C sensor would not be a problem at all for me.

Falling In Love With APS-C Again

With no excuses left, I bought the X-T4, a cropped sensor camera, to be my primary camera as a professional/paid photographer. It felt weird saying that out loud at first, but any insecurities were immediately dispelled as soon as I held the camera in my hand and shot with it.

![]()

![]()

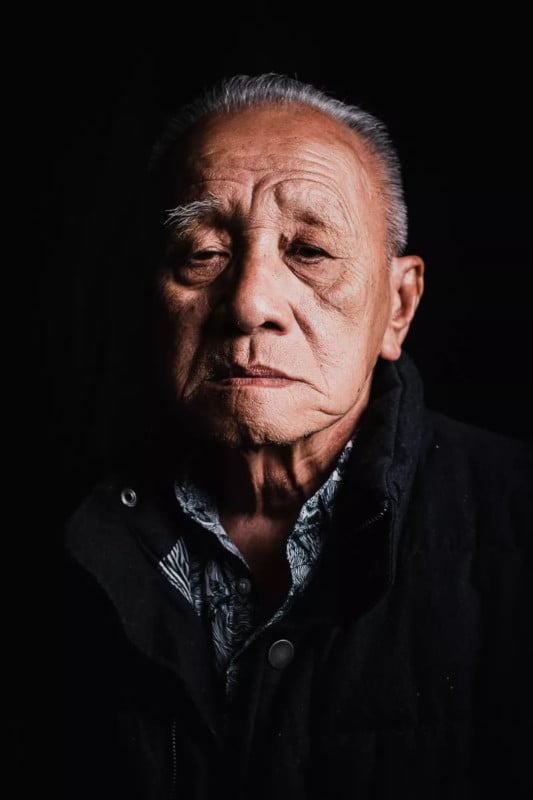

From a living room portrait of my dad to photos of the dinners I cooked (like most people, I didn’t leave the house much for most of 2020), I felt excited about “everyday” shooting again. Make of it what you will, but I do believe how a camera feels in your hand does change the way you shoot.

After owning it for a couple of months, I learned so many things about the X-T4 that reviews couldn’t really show or missed altogether.

The image quality is superb and I very much doubt anyone, including the most discerning of clients, would be able to tell that a shot was taken with a cropped sensor. In fact, many of the movie posters and promo shots you’ve been seeing for big Hollywood blockbusters like Monster Hunter, Joker, and Dunkirk, to name a few, were taken on older Fuji cropped sensor cameras like the X-T2 and X-T3.

With the X-T4 and the 10-24mm f/4 lens, it felt very familiar to my Sony a7 III and 16-35mm f/4 combination – my favorite combination for landscapes. Except, now it was more compact and the 3-way tilt axis LCD screen made it easier to get certain vertical shots in direct sunlight. The X100V’s discreet rangefinder-style body has inspired me to shoot more street “landscapes” and to play more with harsh sunlight and shadows. More than anything, it’s size has me carrying it everywhere I go.

Along with the X-T4, I bought the Fujifilm 35mm f/1.4, the 10-24mm f/4, and the 55-200mm f/3.5-4.8 lens. I’ve also adapted my Voigtlander 50mm f/1.5 lens and a Voigtlander Heliar 75mm f/2.5 for portrait work and bought the Rokinon 35mm t/1.3 Cine lens for narrative filmmaking.

![]()

If I wasn’t so keen on having the IBIS, I would have probably switched sooner to the X-T3 since I’m still so keen on this older model, especially with the release of the X-T4

Here’s the crazy thing. I can fit all of that into my Wandrd 21L backpack‘s bottom compartment. I don’t have to carry all of it with me everywhere but it’s so amazing that I can, when I used to be able to fit just a couple of lenses along with my Sony a7 III in the same bag.

![]()

Final Thoughts

Despite my personal journey to get to this point, I’m not trying to convince anyone to give up their full-frame systems to go APS-C. If I didn’t mind hanging on to multiple systems with a full array of lenses, I would keep all my Sony gear or even reinvest in the Panasonic or Canon full-frame systems.

There are some use case scenarios where I would want the offerings from a full-frame system, like shooting sports. But for everything I do, I’m surprised it took me this long to switch, when all along, going back to the GF-1, I knew that being light, compact and discreet was one of my highest priorities when it came to getting out there and shooting.

About the author: Kien Lam is an international photographer and filmmaker based in San Francisco. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. He runs whereandwander.com and believes in living for those moments that make the best stories, told or untold. He is working through his bucket list and wants to help others do the same. You can find more of his photos on Instagram. This article was also published here.