The New York Times’ Photographic Double Standard

![]()

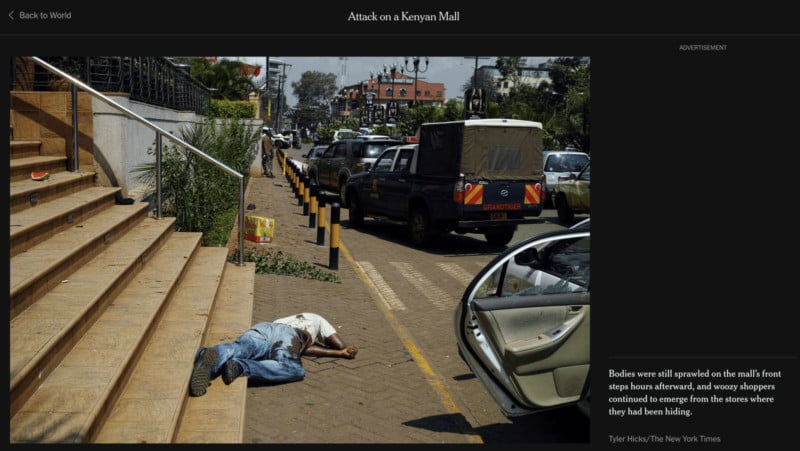

In covering the terrorist attack on a Nairobi hotel that killed at least 21 people by Shahab extremists, The New York Times decided to publish an image of a bullet-riddled body taken by Khalil Senosi. Photo Twitter was outraged, and Poynter wrote about the “hard choice” the NYT made regarding the selection.

Author Tom Jones approached the controversy from the oft-discussed angle of “is it newsworthy?”

In other words, what is the news value? Does the public need to see such an image to fully grasp what happened? Does the public need to see such a photo to confirm or disprove the official account of the events?

Ultimately, Jones concludes that there’s “no question” that the NYT should have run the image.

In discussing his photo of a charred Iraqi soldier from the Gulf War, veteran photojournalist Kenneth Jarecke made a slightly different argument to American Photo, saying, “I think people should see this. This is what our smart bombs did. If we’re big enough to fight a war, we should be big enough to look at it.”

The question for Jarecke was less about newsworthiness as it was about depicting the real cost of something like war.

However, the condemnation on Twitter wasn’t about newsworthiness, but the apparent double standard of showing dead bodies of foreigners in foreign lands, while rarely doing the same within the USA.

Hey @NYTimes, why are you publishing images of dead bodies at the site of the suspected attack in Nairobi?

Do you have no shame?

— Ken Opalo (@kopalo) January 15, 2019

The "choice" wouldn't have been "hard" for had these been white bodies in the geopolitical West.

Instead, @nytimes' thirst for dehumanising Africans did PR work for Al Shabab: free global publicity of their handiwork #NairobiAttack https://t.co/XhYSwZ9K0t— Neelika Jayawardane (@Sugarintheplum) January 16, 2019

This makes me angry.

The @nytimes photo choice did not 'humanise' the terrorist attack.

That should have been evident from the literally hundreds of Kenyans who complained.

This is parachute ethics, and it's as rubbish at the NYT decision. https://t.co/WsSz28aDtH

— Nechama Brodie נחמה (@brodiegal) January 16, 2019

The New York Times defended its decision with a tweet, stating in part, “We take the same approach wherever in the world something like this happens — balancing the need for sensitivity and respect with our mission of showing the reality of these events.”

We have heard from some readers upset with our publishing a photo showing victims after a brutal attack in Nairobi. We understand how painful this coverage can be, and we try to be very sensitive in how we handle both words and images in these situations. https://t.co/Qjm0qBMaF3 pic.twitter.com/1sqgTnnVKW

— The New York Times (@nytimes) January 15, 2019

But while paper and its editorial staff seem cognizant of the issue and willing to ask rhetorical questions about its decisions, the real life decisions seem to suggest a double standard in the way brown and black bodies are depicted. For example, Daniel Berehulaks’ Pulitzer Prize-winning images from the Philippines show an identifiable face of a murder victim – a stark contrast to the common photos of hugging mourners in the USA.

![]()

Below is a list of coverage of mass killings in the USA as initially reported by the NYT. The vast majority of photos can be categorized as either “establishing” or “grief/memorial” shots.

Pulse Nightclub Shooting (June 13, 2016)

- Establishing: 4

- Grief/Memorial: 11

- Bodies: 1 (covered with white sheets)

Sutherland Springs Church Shooting (November 5, 2017)

- Establishing: 3

- Grief/Memorial: 1

- Bodies: 0

Las Vegas Shooting (October 2, 2017)

- Establishing: 0

- Grief/Memorial: 1

- Bodies: 2

Parkland School Shooting (February 14, 2018)

- Establishing: 0

- Grief/Memorial: 2

- Bodies: 0

Thousand Oaks Country Music Bar Shooting (November 8, 2018)

- Establishing: 1

- Grief/Memorial: 4

- Bodies: 0

Photos of injured or murdered children would logically seem off-limits, which partially explains the lack of images from school shootings, but both the coverage of Michael Brown (18 years old and 8 days past his high school graduation) and the Yemeni food crisis prove otherwise.

With the exception of the 2017 Las Vegas shooting which killed 57 people and injured 851 more, the NYT anecdotally doesn’t seem to heed its own policy. The question of newsworthiness will always provoke discussions of ethical norms, but subconsciously enforcing a double standard based on race or nationality is a major blind spot for the paper of record.

About the author: Allen Murabayashi is the Chairman and co-founder of PhotoShelter, which regularly publishes resources for photographers. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. Allen is a graduate of Yale University, and flosses daily. This article was also published here.