In Defense of Steve McCurry

![]()

New York Times Magazine photography critic, Teju Cole, recently penned what could only be construed as a takedown of National Geographic photographer Steve McCurry. Cole is no lightweight. Since its launch, his column On Photography has illustrated his deep understanding of photographic history – not to mention he’s an award-winning writer with a PhD in Art History from Columbia.

Here’s an old-timer with a dyed beard. Here’s a doe-eyed child in a head scarf. The pictures are staged or shot to look as if they were. They are astonishingly boring.

Cole laments that the homogeneity of McCurry’s latest book, India, presents a “worldview” that by settling on “a notion of authenticity that edits out the present day, is not simply to present an alternative truth: It is to indulge in fantasy.”

He offers instead the work of Ragubhir Singh whose gritty work is a stark contrast to the “boring” work of McCurry, suggesting that somehow the more edgy style is a more authentic view of the world. I object.

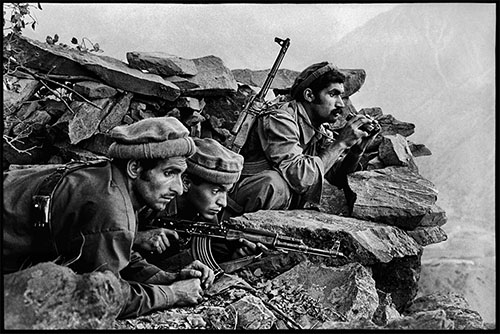

First, let’s dismiss the notion that McCurry is staging photos. McCurry is an award-winning photojournalist represented by the heralded Magnum Photos. The notion that he has spent a career setting up scenes to capture his iconic photos is a massive insult to a talented photographer who started his career at a local newspaper before traveling to Pakistan and sneaking into Afghanistan to cover the build up to the Soviet invasion.

I cannot say with absolute certainty that McCurry has never staged a photo, but to start from the presumption of guilt is nearly libelous.

Just because a photo looks staged (i.e. too perfect), doesn’t mean it is. James Nachtwey’s 9/11 photo of a falling WTC behind the cross on the Church of Saint Peter quickly comes to mind as a “too perfect” photo of an incredible tragedy. But that image was a combination of luck (Nachtwey is rarely in the city) and skill (while everyone else was running, he composed an image and hit the shutter at the right moment).

Cole suggests that the perfectness of McCurry’s photos somehow invalidates them – also slyly suggesting that McCurry’s 1 million Instagram followers is proof of the eye candy nature of his images. Cole’s criticism might also imply that the whole oeuvre of National Geographic photography is boring and “too perfect.” But when you’re a highly skilled photographer taking 250,000 images over the course of 3-6 months for an assignment, and then working with a top notch editor, should anyone be surprised that the photos are exceptional?

Singh traveled across India with Lee Friedlander, who Singh commented was constantly looking for the “abject as subject,” an approach which Singh rejected as a western view. Thus Singh developed his own viewpoint that he considered to be more authentic – neither “sugarcoated” nor “abject.”

I would suggest therefore what we really have is three points of view, and one critic’s preference. All three photographers possess tremendous skill, but Cole seems to revel in the street-style photography of Singh, which is perhaps more akin to the street photography of McCurry’s contemporary William Albert Allard, whose personal work in Paris is a tour de force of multiple points of interest and timing.

Cole’s argument isn’t unique. David Shields lamented the “war porn” he found on the cover of The New York Times, which led to the publication of his book War Is Beautiful: The New York Times Pictorial Guide to the Glamour of Armed Conflict. Shields argues that because war is messy, the photos representing it shouldn’t be beautiful (i.e. aesthetically pleasing). I find this argument puerile. Photos should look the way the photographer intended them to look. The tragic loss of life doesn’t mean that a photo can’t be well-composed.

Cole’s point of view is also a bit of historical criticism with a contemporary lens. McCurry’s Afghan Girl is one of the most iconic and recognizable images of the 20th century. To suggest in the 21st century that it is somehow a vacuous, staged image is spurious. McCurry helped define a style of photojournalistic portraiture that Cole finds objectionable. Cole’s dislike of McCurry doesn’t diminish his corpus. Having an obvious subject with tack-sharp focus and proper exposure doesn’t mean a photo is devoid of layers of interest and interpretation. Likening McCurry’s photos to a Coldplay video…come on, Teju. If McCurry had spent a career jetsetting into town for a day or two to make a couple of stylized images, then I would agree. But McCurry spends weeks, if not months, in the places he’s photographing.

Still, McCurry doesn’t do himself any favors in dispelling the notion that his images look too perfect given his recent commercial work with Pirelli, Dow and Valentino. But given the insulting decline in pay and job security for photojournalists, one can hardly begrudge McCurry for getting paid.

I was unaware of Singh’s work, and I find it incredible. But McCurry is no slouch either.

About the author: Allen Murabayashi is the Chairman and co-founder of PhotoShelter, which regularly publishes resources for photographers. Allen is a graduate of Yale University, and flosses daily. This article was also published here.