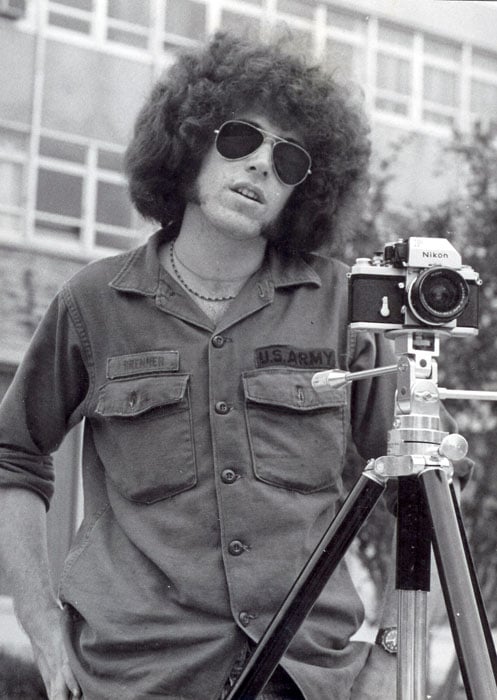

An Interview with Mickey Osterreicher, General Counsel of the NPPA

![]()

Mickey H. Osterreicher is a lawyer who has served as General Counsel of the National Press Photographers Association (NPPA) since 2006. We had a chat with Osterreicher about his life and the state of photographers’ rights.

Mickey Osterreicher: I was born and grew up in the Bronx, New York and left to go to college in Buffalo at 16. Although I wasn’t consciously aware of it I always was the one taking the family photos. I began working for the school newspaper at SUNY Buffalo in my sophomore year and covered many news stories including the anti-Vietnam war protests in Washington and the Democratic National Convention in 1972 in Miami.

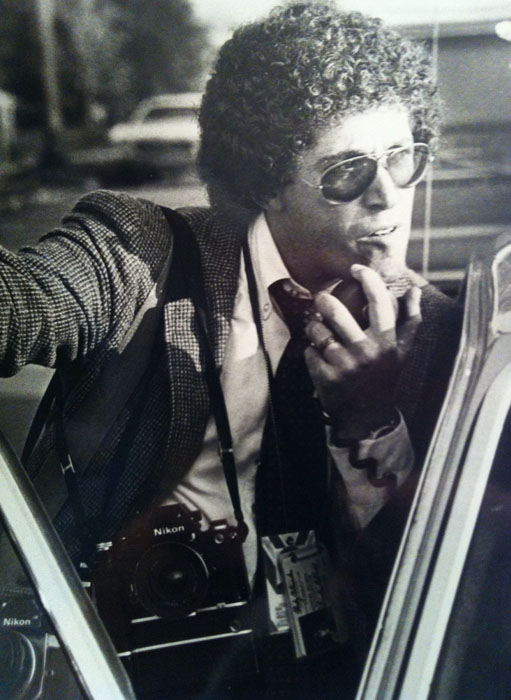

I found I loved photojournalism and began stringing for AP and the NY Times. I was part of the first graduating class of “special majors,” receiving my Bachelor of Science degree in “Photography/Photojournalism” in 1973. Earlier that year I had already been hired as a staff photographer for the Buffalo Courier-Express where I worked until it folded in 1982. I also did freelance work for Time Magazine and many other publications.

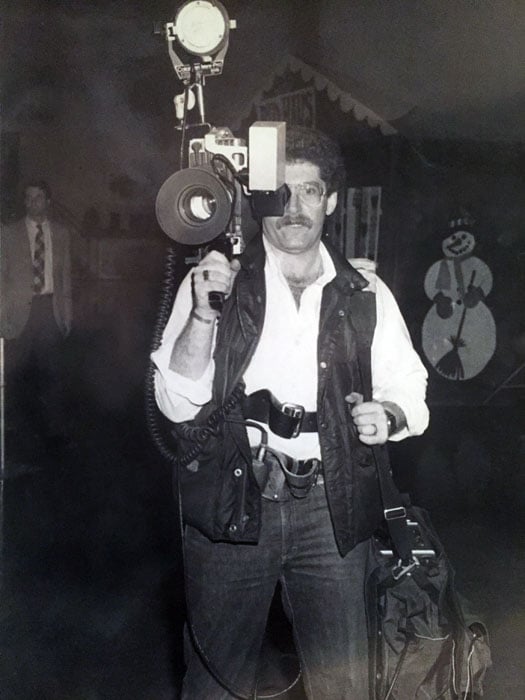

After the paper folded I went to work at the local ABC affiliate, WKBW-TV, shooting and editing video along with field producing and worked there until 2004. I also freelanced for ESPN and a number of other networks as well as shooting stills for Time and USA Today. I went to law school while I was still working at the station (1995-1998, law school 8am – 2pm, work 2:30 – 11:30pm), passed the NYS bar exam and was admitted to practice in 1999.

How did you first get involved with the NPPA?

I joined NPPA in 1973 and continue to be a proud dues paying member. I received a number of awards in both the still and video clip contests. After becoming a lawyer, In 2004 I helped write a brief on behalf of NPPA in support of cameras in the courtroom in NYS. I also wrote articles for the NPPA News Photographer Magazine. I gradually became more involved in working on legal matters for NPPA, becoming its general counsel in 2006.

For me being able to provide legal advice and support, as well as being able to advocate on behalf of photographers is truly a labor of love and my way of giving back to a profession where I never felt like I was working because the stories I was able to tell visually were so enjoyable and rewarding. I am very disappointed in how many photographers no longer belong to any association that speaks on their behalf or take the work we do for granted.

From my perspective photographers are being squeezed from all sides – being interfered with, harassed and sometimes arrested for doing nothing more than photographing or recording in public – to losing their staff jobs – to being offered onerous freelance agreements which seek to take all their rights for little compensation – to seeing their work taken and used by others without permission, credit or compensation. These are some of the reasons why I think, now more than ever, photographers need to join and support organizations such as NPPA so that we may truly be the strong “Voice of Visual Journalists.”

What is your personal background and interest in photography?

I think that I answered that in the first question but to provide a little more – I have always loved visually telling a story and being able to combine using my eyes and working with my hands on the camera, or enlarger or tape editor. I thrive under deadline and have always enjoyed covering spot news and sports where much of what a photojournalist does is instinctual because there are not usually second chances at a one-time shot.

The other thing that you should know is that I have been a uniformed reserve deputy sheriff in Erie County, NY since 1976. I believe that my experience as a photojournalist, member of law enforcement and First Amendment attorney have combined to make me uniquely qualified to provide advice and training to police officers and journalists regarding the rights and responsibilities of both groups. I also think that one of the greatest challenges for lawyers is understanding what it is their clients do. Having worked in both print and broadcast, I understand (sometimes all too well) what the issues are and what photographers are dealing with.

I am also a Trustee of the Alexia Foundation, promoting world peace and cultural understanding through the power of photojournalism and a member of the board of CEPA Gallery, a not-for-profit arts center founded as a resource for photographic creation, education and presentation.

Have photographers always faced the challenges they’re seeing now, or have things become much more serious and widespread over the past several years?

I think photographers have always faced obstacles but a number of factors have created a “perfect storm” of challenges which photographers now must weather. Lately it seems that anyone seen out in public with a camera is viewed as suspect. From police and security who question those photographing buildings, airplanes or trains (for example) because they fear it may be a part of some terrorist plot, to parents wary of anyone photographing children. We are also faced with an economy where photographers are losing their staff positions in broadcast and print, forcing them either to change careers or freelance.

Compounding these problems is the fact that almost everyone now has a camera in their cellphone capable of taking high quality stills and video which may be instantly uploaded and seen by millions around the world moments later. Hundreds of millions of such images being shared online and in social media on a daily basis has contributed to photography being devalued. Because of that many publications and businesses have changed their agreements – offering lower day and space rates while at the same time seeking broader usage licenses. The greatest threat to photographers comes from the widespread belief that the Internet is the “public domain” and any images found there are free-for-the-taking.

This mob mentality of entitlement has led to infringement of images on an unparalleled scale. In those cases where photographers seek to enforce their copyright, the courts have made rulings expanding the “fair use” doctrine. What began as an exception to copyright law now has been turned on its head with copyright seemingly the exception to fair use.

What are your thoughts about the current state of copyright law and the systems that protect photographers? Do things need reform and change? If so, in what ways?

As stated above I believe that the protections previously embodied in copyright law have been eroded. Because the only place where a copyright infringement lawsuit may be commenced is federal court it has become increasingly difficult for creators to enforce their rights when it costs more to bring a claim than one can expect to recover (even if they win).

The NPPA along with a number of other associations representing photographers and visual artists have been advocating for a copyright small claims tribunal and just this week presented a paper in support of that proposition. This would allow for a streamlined and less costly alternative to federal court and has the support of the U.S. Copyright Office which may be read in their 2013 report.

Another issue we are working on which needs to be addressed is the registration process for both published and unpublished works.

Are there any legal cases in the courts or on the horizon that will have a major impact on photographers for years to come?

The Authors Guild v. Google case which may be heard by the U.S. Supreme Court will have a major impact on photographers and all creators. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruling in Cariou v. Prince has expanded fair use in a way that encourages the misappropriation of images and it will be interesting to see how the new lawsuit by Donald Graham against Richard Prince plays out in either expanding or limiting that use. The Lenz v. Universal Music Corp. case is also one to keep an eye on as it addresses fair use in the context of a DMCA takedown notice.

Can you quickly explain what Authors Guild v. Google is and how it might impact photographers in the future?

Whenever I talk about copyright law I begin the program with the PowerPoint slide – It’s Complicated! – which is just as true, if not more so, in Authors Guild v. Google. In December 2004, Google announced it would start scanning millions of books from the collections of leading research libraries to create a comprehensive database that would be searchable online. The project would also benefit the participating libraries, which wished to digitize their collections. The Authors Guild commenced a lawsuit in September 2005 in order to seek fair compensation and effective copyright protection for its members.

Google’s position is that its book-search program offers great social benefit and therefore its copying should be protected as “fair use.” The Authors Guild argued that private companies should not be able to digitize copyrighted works for commercial purposes under the fair use doctrine without compensating the rightsholders. An agreement was reached in October 2008. Google would pay out $125 million, some of which would go to the owners of the books that were scanned without permission and the rest would fund the Book Rights Registry, an organization created to locate and then distribute fees to authors.

Unfortunately, due to much opposition on both sides of the issue, in March 2011 the federal trial court refused to approve the settlement. The case eventually went to trial before a judge. In deciding whether “fair use” applies the court is required to considered independently and then balanced against each other four factors: (1) the “purpose and character” of the use, including whether it is commercial; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work (words, photo, etc.); (3) The amount or substantiality of the portion used; and (4) the effect of the use on the potential market for or value of the work.

In November 2013 the court dismissed the lawsuit finding that Google’s mass digitization was protected under fair use. The Authors Guild then appealed that ruling to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, in New York. In October 2015, that court upheld the lower court decision and “found that the project provides a public service without violating intellectual property law.” The Authors Guild has now asked the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the case. That decision should come sometime later this spring. If the High Court grants certiorari the case would be heard in the fall.

In the meantime, Google has already scanned 20 million books, and displayed “snippets” (short segments) from 4 million that are protected by copyright. The actions by the Authors Guild are not meant to prevent Google’s project, but rather to require it to compensate authors to some degree for the use of their works. This holds just as true for photographers who also sued Google “over the inclusion of visual works in Google Books” but settled the case in 2014.

In what ways have things improved for photographers in recent years or decades, from a legal standpoint?

If we are able to get a copyright small claims tribunal in place sooner than later, I think that will be of great benefit to photographers where they actually have a viable alternative to recover damages for infringing works. It is also my hope that this will discourage the widespread infringement we are seeing today as predators who infringe with impunity and those who take photos without permission due to ignorance become aware of this expedited process. In those cases where the infringement has occurred I hope the tribunal will encourage voluntary settlements.

I also believe the right to record and photograph police officers performing their official duties in public is being clearly established throughout the country which will eventually bring about a cultural change on the part of law enforcement so that they stop interfering, harassing and arresting those exercising their First Amendment rights. I also think that we will see improvements in the regulations covering the use of drones for newsgathering and for photography in general.

Do you think the devaluation of photography and the loss of photography jobs is permanent, or do you think it can be won back somehow? If so, how?

I believe at the rate things are going the devaluation of photography will continue unless and until users of visual works and the public in general recognize their importance and social value.

The ever-increasing misappropriation of visual works also threatens the country’s public health and safety by undermining a profession America has traditionally relied upon to provide it with compelling images and stories.

Most visual journalists view our profession as a calling. No one really expects to become wealthy in this line of work, but most do expect to earn a fair living, support themselves and their family, and contribute to society. Copyright infringement reduces that economic incentive dramatically. This in turn may abridge press freedoms by discouraging participation in this field. It also devalues photography as both a news medium and art form, thereby eroding the quality of life and freedom of expression that are part of the foundation of this great nation.

In a digital age of ever-expanding creativity and consumption, updated legal principles and new legislative mechanisms are needed to ensure that copyright law remains viable. The rights of photographers and the needs of users must be integrated into a functioning system that incentivizes and rewards creativity and innovation on both sides of the issue while simultaneously recognizing an inherent right of creators to exercise at least some control over the use of their works. Such an updated and “fair” copyright system is imperative if the exclusive protections imbued in copyright law and the threat to photographers’ ability to receive fair value for their work are to be reconciled with freedom of expression.

Is there anything else you’d like to say to PetaPixel readers?

As I said earlier, I see photographers being squeezed on all sides and yet I also believe that sometimes we are our own worst enemies. There are a number of things that photographers can do to help themselves. Don’t work for free or for unacceptable payments (day rates or licensing). While it may be difficult to say no to a job – that may be better than losing money with each shoot you do take (see NPPA cost of doing business calculator).

But don’t just say no – educate others as to the value of our work and explain why it should not be undermined. Register your work with the Copyright Office so as to better be able to enforce your rights.

Take personal accountability for your actions. Recent examples that come to mind: the way NPPA student member Tim Tai comported himself in the wake of being accosted by Missouri University Professor Melissa Click or photographer Christopher Morris in his interaction with a Secret Service agent at a Trump rally.

While so many photographers are quick to complain about their plight there are far too few who join or support organizations such as NPPA. Even those that do ask the wrong question. It is not so much about what NPPA can do for you but what you can do for NPPA – and through that effort – do for photography as a profession.

In these tough economic times, rather than lament that you cannot afford the annual dues it would be far more effective for photographers to belong so that as “the Voice of Visual Journalists” NPPA can speak with a much louder and stronger voice. Does anyone believe that the NRA would be as effective (rightly or wrongly) without its claimed 5 million dues paying members? We cannot do these things alone. As Benjamin Franklin so astutely noted, “we must all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately.”

Michael, thank you for the opportunity to answer your questions and discuss my views. I truly hope your readers will take some of what I have said to heart.

Image credits: Header portrait by Cathaleen Curtiss