An Interview with Sports Photographer Brad Mangin

Brad Mangin is a freelance sports photographer based in the San Francisco Bay Area. He regularly shoots for Sports Illustrated and Major League Baseball Photos, and he has photographed 19 World Series and a number of Super Bowls and NBA Finals so far. We had a chat with Mangin about his life, career, and love for sports photography.

Brad Mangin: I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area in the east bay city of Fremont, where I lived with my mom and dad, and my sister Paula. My dad was a high school basketball coach for 32 years and a former division I basketball player at Pacific in the 1950’s who played against the great Bill Russell teams at USF. Sports were always big in my family. We went to all of my dad’s games, played endless games of basketball in our driveway, and watched tons of sports on television.

My favorite sport as a kid was baseball, and my favorite team was the San Francisco Giants because my dad and older sister rooted for them. During those years the local Oakland A’s were winning three consecutive World Series titles in ‘72, ‘73, and ‘74 but I remained loyal to the Giants who were just awful. I am from the generation of kids who went to sleep with their transistor radio under the covers listening to night games (the Giants only televised 20 games a year back then — all road games) and soon my dream was to be a radio play-by-play guy so I could call baseball games and get paid to go to the ballpark every day.

How did you first get into photography?

In high school my best friend Joe Gosen (who now teaches photojournalism at Western Washington University) talked me into taking a basic photography class in the second semester of my junior year. Joe had taken a class from our photo teacher at Washington High in Fremont, Paul Ficken, and loved it. From day one of the class I was hooked, especially when Joe lent me his Pentax ME-Super to shoot my first roll of Kodak Plus-X black and white film (this was 1982). At the time I was washing dishes, bussing tables, and wearing the mouse costume at Chuck E. Cheese saving money to buy a used car that summer. Instead, I bought a Canon AE-1 Program and dove head first into photography.

What kind of a photography education did you have?

During my senior year of high school I worked on the yearbook staff and had many more classes with Mr. Ficken. I learned so much from him. Joe and I both decided we wanted to pursue photojournalism and enrolled at our local junior college, Ohlone in Fremont, in the fall. Our goal was to get an AA degree in photojournalism and then transfer to the legendary PJ program run by Joe Swan at San Jose State. We started at SJSU as juniors in the fall of 1986 and were lucky to be there with a great group of fellow students. We all learned so much from each other, and were lucky to catch the end of Mr. Swan’s career at school and the beginning of Jim McNay’s when he came to campus to run the PJ program in 1987.

How did you cut your teeth as a professional photographer?

Back then all any of us ever wanted to be were newspaper photographers. Our heroes worked for the local papers in the Bay Area. I interned for the Contra Costa Times in Walnut Creek in the east bay in 1987 and 1988 and learned from some amazing staff photographers like Dan Rosenstrauch and Jon McNally who are still very good friends or mine. I was hired by one of their smaller papers in the chain when I graduated in 1989 and was thrilled to have a staff job in the Bay Area working nights and weekends while shooting tons of black and white film at high school and Little league games. I attended the second Eddie Adams Workshop in the fall of 1989 and was having a great time at my job. Then I got a huge break.

In June of 1990 I was hired by legendary photographer Neil Leifer to be the San Francisco-based staff photographer for The National Sports Daily. The National was a new idea for a daily sports paper in the United States, just like they had all over the world in countries like Germany, Italy, and Spain. Renowned sports writer Frank DeFord left Sports Illustrated to become the editor of the massive New York-based project and Neil was the director of photography. Before I knew it I was covering sporting events all over the place and sending pictures back to our picture desk in New York over analog phone lines with an AP Leafax transmitter that took 30 minutes to send one color picture — and that was state of the art at the time!

I was 25 years old shooting the World Series, Super Bowl, and NBA Finals all in the same year. I was having an amazing time and learning every step of the way as I worked with and met some amazing photographers and editors. It was a great run while it lasted but in June of 1991 after I had been at the paper for one year we folded when I was with fellow staffer and good friend Chris Covatta covering Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls as they won their first NBA title over the Los Angeles Lakers in Game 5 of the NBA Finals at The Forum. Our owner, the richest man in Mexico, had put up $100 million to get the paper going. It was supposed to last 5 years. The money was gone in 18 months.

When the paper folded I was a mess. It was an incredible job. I thought it would last forever. I had it made. Next thing I knew I was cashing rainbow-colored unemployment checks after waiting all day for the mailman to deliver them.

What was the next step in your career?

I kicked around for a year stringing for the Associated Press in San Francisco before a got a job at a small newspaper. It was a very difficult time for me. Jobs were hard to come by and I didn’t want to leave the Bay Area. At the same time I was trying to freelance as a sports photographer using some of the contacts I made while traveling the country working for The National. While working at the small newspaper I started shooting assignments for the NBA and Upper Deck. Thanks to Neil Leifer’s help I got my foot in the door at Sports Illustrated where I was given the chance to shoot a few assignments in late 1992. They were testing me and luckily I didn’t screw them up.

By the middle of 1993 my newspaper job was not going well and my father was dying of cancer. It was the worst time of my life. I was 28 years old. My dad died on July 9 and I quit my newspaper job a few weeks later to freelance fulltime. The San Francisco Giants were having a great season and I started shooting many of their games on assignment for Sports Illustrated and things took off for me in a good way. The 49ers were also very good at the time so NFL assignments followed. When I wasn’t shooting for SI I shot for Upper Deck.

In the winter I shot several basketball games for the NBA. It was a really good time for me. I was learning to become a better photographer and businessman by fire. It was a crash course in learning right before the Internet started. I bought a FAX machine and typed up invoices on carboned white, yellow, and pink copies. I did all my accounting by hand. In 1994 I finally got my first computer, an Apple Powerbook 520c. Pretty soon I had an AOL account and all my accounting work was moved to Quicken and Filemaker. I was on the cutting edge!

In 1994 I started shooting for Major League Baseball, which is a great relationship that still stands today. In fact I just shot my 16th straight World Series for them in Kansa City and New York in the fall of 2015.

The rest of the 1990’s were pretty smooth with work, more and more of it from SI. With the help of my before-mentioned friend Joe Gosen I launched my first portfolio website manginphotography.com in 1998. Joe built it for me with Adobe Pagemill and it was very cool. Joe was also a huge part of another website collaboration I was involved with in 2002 when I was a part of a team that launched SportsShooter.com (along with Robert Hanashiro, Jason Burfield, and Grover Sanschagrin).

How has sports photography changed over the past decades?

The simplest answer is the technology. I always sound like an old guy when I talk about “how things were when I started.” But they sure were different. Two big things. Autofocus and digital. When I started you had to manually focus and you had to shoot film. This mean you had to have incredible hand-eye coordination and you had to have your brain working all the time to be able to figure out the exposure on the field when the light was changing, especially if you were shooting color slide film for a publication like Sports Illustrated.

Back then, if you were shooting a commercial job for an ad or for a poster company or trading cards like I was for Upper Deck or for a magazine like the Sporting News, SPORT, Inside Sports, or Sports Illustrated, etc. you had to shoot color slide film, or transparency film. This film has no latitude in exposure and there was no Photoshop to help you. Your exposures had to be perfect. If your slides were too light or too dark they were in the trash can, and we haven’t even talked about if they were in focus yet.

The Minolta light meter around your neck was your best friend. You kept it calibrated and took great care of it. You knew that backlit batters at Candlestick Park shot from first base were 1/500th of a second at f/4.0 with Fujichrome RDP 100 pushed a stop to 200 because the dirt in the batters box kicked in an extra 1/3 stop of fill light. If the guys were on the grass the exposure was 1/3 of a stop darker. You had your little metering tricks for every situation and you needed to build up confidence because you had to ship your raw, unprocessed film to your editor. Sleeping at night could be problematic if you did not have confidence in your exposures.

Focusing was an entire different skill. There were national legends like John Biever and Andy Hayt at Sports Illustrated who were the best manual focusers in the world. They could shoot a football game with a 600mm lens and rack focus and entire sequence of a running back coming straight at them with every frame tack sharp. Mere mortals were thrilled if they could get one frame that was tack, and a few that might be “sharp enough” to run in a newspaper with bad reproduction.

Each local area had newspaper legends that were the best sports shooters because they could focus like no one else. Here in the Bay Area it was John Storey with the San Francisco Examiner. John is the best sports photographer the Bay Area has ever seen and covered the Joe Montana 49ers like no one else during their heyday. John nailed every big play in focus. He never missed. He had a skill that no one else around had, which made him the best.

The first autofocus that came out that was worthwhile was the Canon system with the EOS-1 film camera in 1989. At the time they had a 600mm 4.0 and a 300mm 2.8 (a 400mm 2.8 would soon follow) and some people, including myself started to try it out to see if it worked. Oh man did it work. Before you knew it sidelines at sporting events were littered with white lenses for the next several years as many sports photographers went Canon, simply because of their terrific autofocus technology. We started seeing more and more pictures of wide receivers in mid-air catching passes and shortstops diving for line drives. Of course guys like Biever and Storey didn’t need the new stuff and still kicked everyone’s ass by manual focusing, but the field was being leveled.

Digital SLRs finally became viable for publications like Sports Illustrated in late 2002 with the advent of the Canon EOS-1D. This was the first camera that SI decided produced a good enough file that they could run as a two-page spread in the magazine (by shooting RAW). All of us that shot for the magazine had to switch to digital and the famous TIME-LIFE Photo Lab was shut down. No more Fujichrome for us! Of course, newspapers and wire services had been shooting different forms of digital for over a decade to varying degrees of success, but now the playing field was truly level. We were all shooting with the same cameras and with the exposure latitude of digital, especially when shooting in RAW, it became so much easier to shoot sports.

Digital cameras with autofocus and a screen on the back of the camera so you can see your pictures after you shoot them? Are you kidding me? Now I can sleep at night! I know if that play at the plate is sharp right after I shoot it. I don’t have to worry if the frames are sharp on that roll of film on United #78 from SFO to EWR flying at 35,000 feet over Iowa as I try to sleep.

Today’s digital cameras, it doesn’t matter what brand you shoot, are incredible. In the old days if you had to shoot a night game it meant your pictures would look like shit. Color negative film like Kodak Ektapress 1600 film meant your images would be dark, yellow, and grainy as hell. Nowadays the stuff we shoot at night is breathtaking. I just finished shooting the World Series and my pictures shot at ASA 2500 or 3200 are incredible — and of course they are tack sharp!

What are the challenges facing sports photographers these days?

The big challenge these days is finding someone who will pay you to shoot a game for them. It’s very simple. There are not many clients left who will pay for working photographers to create original content at a ballgame of any kind. The market is flooded with free/cheap wire pictures that are good enough for most end users. For over 20 years my main client as a freelance sports photographer was Sports Illustrated. I earned the bulk of my living by shooting paid assignments for them, keeping my copyright, and earning secondary income from future space rates in the magazine and stock sales through various agencies. That was a viable business model for decades and decades. Not anymore. Those days are long gone and they aren’t coming back.

I fought very hard to keep my copyright over the years. I refused to sign bad contracts and built up my personal online searchable archive powered by PhotoShelter with over 86,000 captioned images (including over 6,0000 scanned chromes) going back to 1987. I used to think that archive would be a huge part of my retirement. Unfortunately, now it looks like my archive is as valuable as a shoebox full of Joe Charboneau rookie cards.

What’s it like to make a living from sports photography these days?

It has become incredibly difficult to earn a living as a sports photographer these days. No one wants to pay for special, exclusive content anymore. Most end users are satisfied with cheap/free “good enough” wire pictures or handouts that will fill a hole on a website or take up space in one of the few print publications left. Gone are the days when publications have the budget to send photographers to games because they want to get a first and exclusive look at what that photographer sees and shoots during a sporting event. The business model that many of us successfully used for several decades does not work anymore and it is very scary.

Do you think the devaluation of photos and photographers is permanent, or do you think it’s something that photographers can help reverse?

I try to be positive about stuff like this, but I have never seen licensing fees for images or creative fees for photographers go up once they have dropped so low because of supply and demand. Of course I am mostly familiar with sports photography as a profession, but much of what I say goes across many of the expert disciplines my colleagues practice, be it high-end portraiture or documentary photojournalism. As long as there are people willing to work for free, or allow their images to be used for free, or almost free it will be tough to get the end users to pay again for original content like they used to in the old days. I really hope I am proven wrong.

Do you think sports photography will continue to be dominated by DSLRs by Canon and Nikon? Do mirrorless cameras stand a chance in the industry?

I really don’t know. I have never used or even touched any of the new mirrorless cameras made by Sony, etc. I know many photographers are using them to shoot everything possible — including sports. I just don’t have any first-hand knowledge to give a well-informed opinion about this topic.

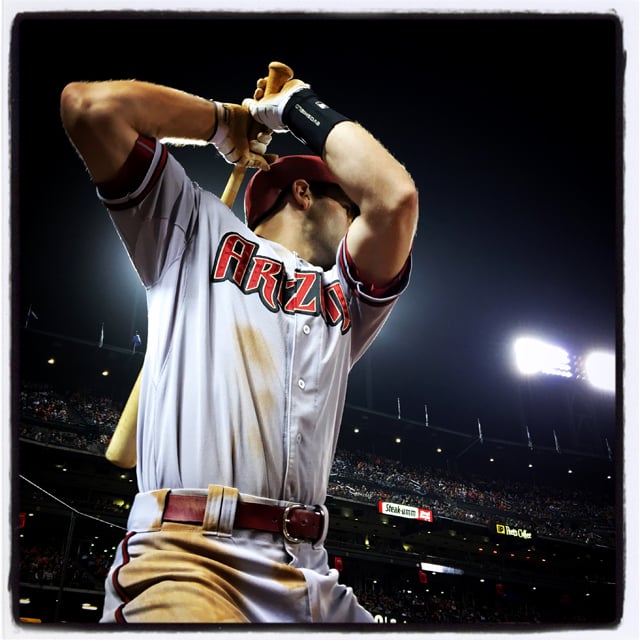

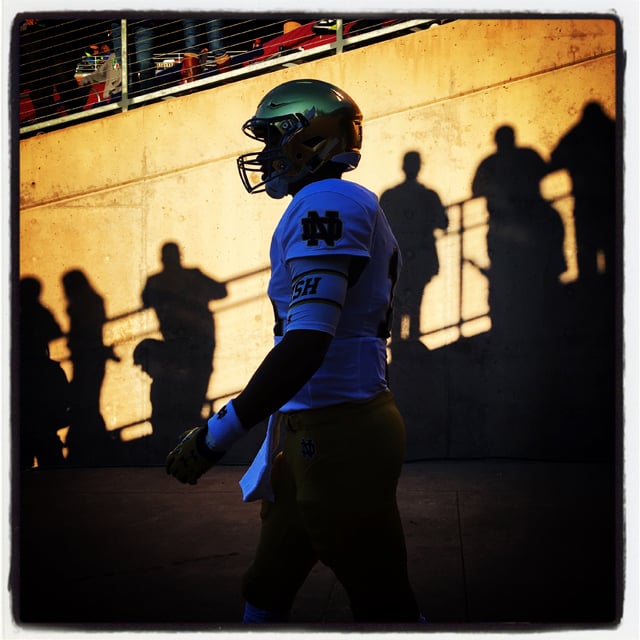

How does your iPhone camera and Instagram account play a role in your work these days? Have there been any unexpected benefits of having over 100,000 followers on @bmangin?

I absolutely love shooting pictures with my iPhone and sharing them on my Instagram account. The trill of sharing my work has never wavered. There are some days when the one or two iPhone pictures I share on Instagram give me way more satisfaction than anything I shoot with the DSLR at a sporting event. Just the other day I was shooting a college football game between Notre Dame and Stanford in Palo Alto, California on assignment for Sports Illustrated. Besides shooting the game with my Canon cameras my goal was to get one really nice picture with my iPhone before the game that I could share on both my Instagram account, and the SI Instagram account with 728,000 followers @sportsillustrated. I got a really nice picture of the Notre Dame starting QB coming out of the tunnel for warm ups in some crazy light that I just loved. I couldn’t wait to tone and caption and image so I could share it with everyone.

It was definitely the best picture I shot all night until Stanford won the game 38-36 with a last-second field goal. By then I finally redeemed myself and got some really nice pictures of the end of the game with my DSLRs.

I have really enjoyed having lots of followers on Instagram. To date I have not had any crazy benefits because of this. I have been recognized by many people because of this and had an iPhone picture of mine featured in the Apple “Shot on an iPhone 6” campaign.

What’s your single favorite photo that you’ve captured, and what’s the story behind it?

I don’t have any single favorites. There are many that I like, but being the tortured artist that I am I hate most everything I do. I am a tough critic! I always hope that I will shoot my favorite picture at my next game. After all it is sports, and anything can happen. It is all unscripted and that is what I love about it. You never know.

What are some things you’d love to shoot but haven’t gotten a chance to yet?

I have been incredibly lucky as a photographer. I have shot almost everything I would ever want to shoot. The Little League World Series that takes place every August in Williamsport, Pennsylvania might be the one event that is missing from my resume that I would love to shoot the most. I loved shooting Little League games when I worked at newspapers in the late 1980’s. The kids at that age play with such passion and energy. They show great emotion on their faces when they win and when they lose.

I have always watched this event on television since I was a Little Leaguer in the 1970’s when Williamsport looked like the most perfect place on earth. Many of my friends have shot there over the years and made some incredible pictures. There are always some games played in fabulous afternoon light, making me so jealous when I watch from my living room in high definition on ESPN. I think I could make some fun pictures at the Little League World Series if I ever get the chance.

What are some of your best simple tips for shooting better sports photos?

My simple tips for better sports pictures can also help you in other types of photography. I want to see great light, a great face, and a clean background. That’s the dream. If you go to a youth soccer game and there is a parking lot on one side of the field and pine trees on the other side of the field, shoot with the trees in your background. You don’t want to have ugly fences and cars in your background.

The first thing I do when I go to shoot someplace is look around and pick out the ideal background for my pictures. Sometimes I feel like a painter. I want to “paint” a perfect photograph by picking my background canvas. Once I do that I wait for the action to come to me. When things are going really great there is terrific light to go with my great background. Of course I have spent many days waiting and waiting to make a special picture with the ideal light and ideal background but nothing good happens in front of my canvas. That’s OK. I still made some decent pictures, just nothing fabulous. At least I had a plan and I will work hard to do it again the next time I shoot.

I learn something each and every time I shoot a ballgame. I have been doing this for almost 30 years and I shoot close to 100 games a year. I study my work. I look at the work of other photographers I admire. Why are my pictures not very good today? What could I have done differently? What would have happened if I would have gone up high to shoot down? Should I have shot wider? Should I have shot tighter? That’s what is so much fun about photography. This aint math. We are not racing against a stopwatch. This is a subjective art that we are always striving to master, but we never will. I know that is something that keeps me going. Every day I go to the ballpark I believe I will make a great photograph. I have no idea what that might be, but I know it’s out there somewhere.

What advice do you have for an aspiring sports photographer who’s trying to “make it” in the industry?

I joke with young photographers that they need to inherit a big pile of cash, marry someone who has a great job with benefits, and never plan to make any money. That way you will be able to afford the insane amount of money the camera manufacturers are charging these days for top-of-the-line cameras and 400mm f/2.8 lenses that you need to shoot sports with, because it is virtually impossible to pay for the gear, camera insurance, health insurance, liability insurance, rent, car, gas, power, computers, retirement, and everything else you need to run a successful and profitable business on the amount of money that is being offered by end users to photograph sporting events today. I really can’t sugar coat this.

I have been doing this for a long time at a high level, but I am nearing the end of my rope and am struggling to pay my bills each month. I had a really good business model that worked for 20 years. It doesn’t work anymore and if I don’t come up with something new real fast I am in big trouble.

What does this all mean? I would never try and take someone’s dream away. Just take what I say as a warning from someone who has been there and seen it from the inside. Be better than me. Be smarter than me. Be luckier than me. There will always be the chosen few who are good enough to play center field for the New York Yankees, and there will be always be the chosen few who make it in this business. Just not nearly as many as in the past.

Is there anything else you’d like to say to PetaPixel readers?

I absolutely love photography. I love everything about it. I have over 500 photography books in my home library and over 100 signed, matted, and framed 11 x 14 prints hanging on the walls of my private photo gallery in my home. I have made my living as a professional photographer since I graduated from college in 1988. There is nothing I would rather do. I have been incredibly lucky.

As a kid I dreamed of being able to attend every San Francisco Giants home game. At one point I thought the ultimate would be if I could sell hot dogs at Candlestick Park as a teenager, but that was not logistically possible living so far away. Then I thought I would be the next Giants radio play-by-play announcer so I could get paid to attend every game. I eventually became a sports photographer specializing in baseball, where I have been able to photograph well over 1,000 Giants home games since 1987.

In that time I have documented them winning three World Series Championships and published books after each title season. It has been a dream. I never got in this to get rich. I simply wanted to share my vision of the game I love with others. I think I have done a good job of this over the past few years and I am only getting better. Unfortunately it is getting harder and harder for me to survive as a photographer these days as no one wants to pay me to shoot baseball games anymore. I have had a great run, but I aint giving up, yet!

If you love photographing something go after it with everything you have. Become an expert in that field and chase it with all your heart. If you love something you will do a better job photographing that subject better than someone who doesn’t. The passion you have for a subject, be it rock and roll or portrait lighting or documentary work is the driving force that will set you apart. You will never have much money, so that must be OK with you (unless you followed my advice above and married well or inherited a huge pile of cash!). Chasing the dream takes time, but the journey is such an entertaining, incredible learning experience that it is not to be rushed. Enjoy the journey, and hope it never ends.