The Three Eras of Photography: Plate, Film, and Digital

![]()

After being invented in the early 1800s, photography and cameras have gone through three major eras: the plate era, the film era, and the current digital era. This article is a brief history of photography through the lens of these eras.

The Plate Era

On January 7, 1839, Louis Daguerre made a presentation to the French Academy of Science, basically a news conference, where he demonstrated the first photograph, a silver image on polished metal. A few days later an Englishman named William Henry Fox Talbot called a conference to announce that he had been making photographs on paper for several years. Thus, the controversies and the Plate Era of photography were launched.

By 1851 glass was being used for making the negatives that could be contact printed onto paper. The glass was coated with a light-sensitive emulsion in a darkroom, loaded into plate holders, and exposed in the camera. The glass plates then needed to be developed before the emulsion dried; this was a matter of minutes. This system worked well in a studio or controlled environment, especially where two or more people could work together. One coated the plates, another operated the camera, and perhaps a third developed the plates.

This was considerably more tedious and precarious on location. The early pioneer photographers traveled with a black tent and crates of glass plates, as large as 11×14, and bottles of chemicals, documenting the country, from the Civil War battlefields to Yellowstone National Park.

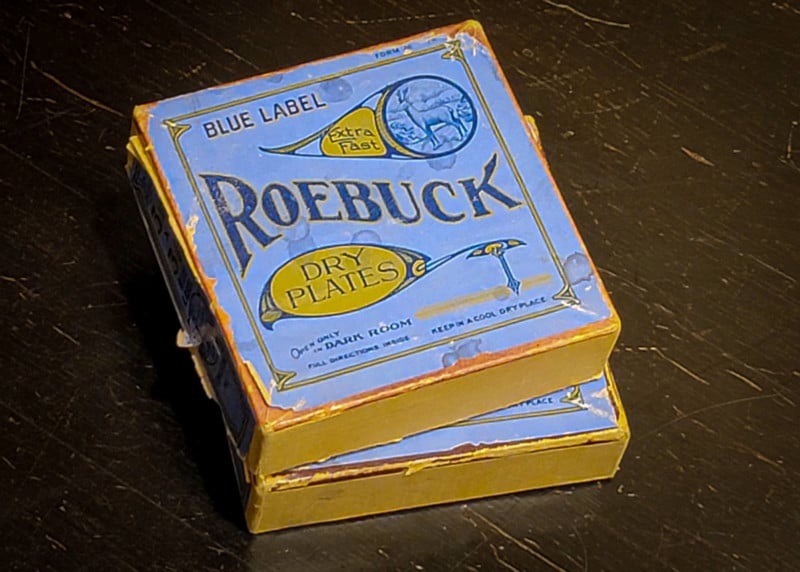

In 1867 a new process was invented in England that allowed the plates to be coated in a factory and sold to photographers ready to expose. This also meant that they didn’t need to be developed immediately but could be taken back to a fixed darkroom location to be developed and printed. This made location and travel photography much easier.

Wet plate cameras and plate holders can usually be identified by the chemical stains in the holders and inside the camera. Cameras from the dry plate era are usually clean inside because they were never exposed to chemicals. Between wet plates, dry plates and various other processes such as tintypes and ambrotypes, the 19th century was clearly the “Plate Era” of photography.

The Film Era

In 1884, a Rochester, New York-based dry plate manufacturer named George Eastman invented a process and a machine for coating the photographic emulsion onto a flexible material. He designed and sold a roll film adapter for plate cameras but faced a difficult market because the long rolls required special equipment and were harder to process than glass plates. Additionally, the film was hard to hold flat which resulted in unsharp images.

Eastman realized that he needed a whole new system based around rolls of film. In 1888, he introduced the first camera designed for use with roll film that he called “The Kodak.” The name of the camera was chosen based on the sound the camera made when an exposure occurred. His slogan was, “You push the button, we do the rest.”

The customer bought the camera pre-loaded with enough film for 100 photographs. They then mailed the camera back to the Kodak company in Rochester where the film was processed and printed. The camera was reloaded with film and mailed back to the customer with the 100 prints.

The first Kodak sold for $25 and developing, printing, and reloading cost $10. $25 back then would be the equivalent of about $750 in 2022 dollars, and $10 would be about $300.

The next revised models of the Kodak were reloadable by the customer and came in short rolls of 8 to 12 exposures. A lower-priced Kodak called the “Brownie” was introduced and by the turn of the 20th century in 1900, the whole world was “Kodaking,” and the Eastman Kodak Company became the dominant photography company in the world for the entire 20th century.

The twentieth century was the “Film Era” of photography, and Eastman Kodak was THE photography company of the 20th century suppling the vast majority of film, paper, and chemistry. The original Kodak not only launched a world of amateur photography but spawned the entire photofinishing industry and all of its branches as well.

Throughout the 20th century, from 1900 to 2000, a wide variety of film cameras, sizes, and quality levels were available. Low-priced roll-film cameras such as the Brownie and later Instamatic allowed just about everyone to make photographs of their families, friends, and travels. At the same time, film cameras made by companies such as Nikon, Canon, Pentax, and Leica took photography to a new level. When Kodachrome color film was introduced in 1936, it brought with it the standardized 35mm film cassette which allowed the same film to be used in all 35mm cameras.

During the heyday of film, Kodak had two totally separate divisions, one for the consumer market with films such as Kodacolor, and a second professional division with film and paper aimed at the professional and pro-lab market. At the most basic, the Eastman Kodak Company was a chemical company, and their product was chemical-based photography.

The Digital Era

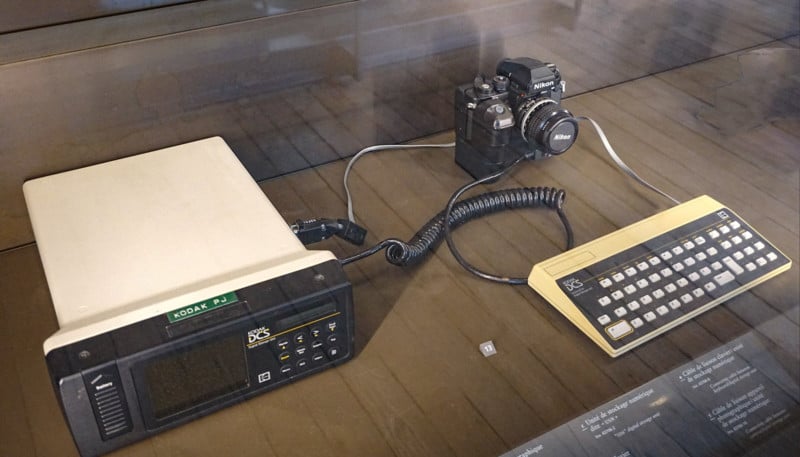

In the mid-1970s, a small group of scientists at Eastman Kodak began experimenting with electronics-based photography. Not just video, but a new method of storing images using digital technology. The camera used a special back on a standard Nikon and stored the files on a separate hard drive. By the 1990s Kodak was offering digital backs for well-known 35mm cameras such as Nikons and Canons. Since Kodak was a chemical company, management didn’t see any future in digital photography and if they did, it was considered a threat to the core business of film, paper, and chemicals.

The threat was real. The digital era left Eastman Kodak in the dust and eventually bankrupted the company. Kodak’s failure to make the shift to digital will be textbook case studies in business schools for years to come.

Eastman Kodak’s lack of vision left the advances in digital photography to the companies that had been making precision cameras all along and were anxious to distance themselves from the whims of the “Yellow Father” in Rochester. Even more prepared were the giant electronics companies such as Sony and Panasonic which were accustomed to rapid technology changes and were not tied to the legacy technology of film.

Digital technology improved rapidly, and prices continued to drop until digital photography had a clear advantage over film. It hit the tipping point at the turn of the 21st century, the year 2000.

By 2002, most major camera manufacturers had 5-megapixel cameras in the $1,000 to $1,500 range. This put them within the budget of serious photographers who were anxious to take full advantage of software such as Adobe Photoshop and were ready for all of the conveniences of digital photography.

Early in the development stages of digital, some people predicted that digital cameras would have to have 30-megapixels to be equal to even 35mm film, much less larger formats. At the time it appeared that even 1-megapixel cameras were a distant dream. It turns out that since digital cameras use one chip for all three colors, the total needed was only 10-megapixels.

Also, that prediction missed the fact that film is always at least a second-generation image – negative to print. Even a projected slide is degraded by a projection lens. A digital image is always first-generation by definition, even if copied, so 5MP cameras equal 35mm in resolution. Cameras in the 12-15 megapixel range can easily surpass medium format film quality.

From the 19th-century plate era to the 20th-century film era, to the 21st-century digital era, almost to the date, the history of photography fits into the calendar perfectly. Anyone living to witness the 22nd century and what that might be like for the imaging world will certainly be amazed at what that future will hold.

Image credits: Header digital camera photo from Depositphotos. All other photos by Jim Mathis.