The People Who Make Your Photography Dreams a Reality

![]()

I recently returned from an incredible trip to Canon’s Tokyo headquarters and Utsunomiya lens factory. While the sights and sounds of Tokyo and Utsunomiya are undoubtedly spectacular, and I will carry these memories with me for the rest of my life, it was the exceptionally rare peek behind the curtain of Canon — one of the most popular and celebrated camera companies — that made the most powerful impression.

Every single aspect of a Canon camera and lens requires countless people working across many different teams. Each function, big and small, and every component in every camera and lens, requires dozens to hundreds of people working five days a week for months and, in many cases, years. Some innovations take over a decade of work behind the scenes to ever be implemented into a project, and many more ideas never work at all.

![]()

Full disclosure: I was invited by Canon alongside a handful of my colleagues to visit Japan and gain unprecedented access to Canon Inc., the beating heart of Canon’s global operations. Although Canon did not have editorial control over this story, nor did it require there be a story at all, it is nonetheless worth noting that Canon extended the initial invitation and paid for the trip.

With that important note out of the way, let’s dive right in and take an exceptionally rare peek behind the curtain at Canon’s operations.

A Company of Passionate Photographers

As I entered Canon’s headquarters, I was immediately struck by the massive size of Canon’s imaging department and its abundance of people who are passionate about photography. Behind the ubiquitous Japanese corporate uniform of slacks, dress shirts, and jackets are people who are deeply invested in photography’s history, present, and future.

For example, Canon’s Executive Vice President, Head of Imaging Group, and Chief Executive of Imaging Business Operations, Go Tokura, got his start at Canon as a product designer. One of his earliest and, as it would turn out, impactful projects in his early days was the Canon T90 in 1986. This camera would ultimately influence the design of every Canon EOS camera that followed.

He loves photography, which has significantly informed his contributions at Canon from his early days to his current role near the very top of Canon’s imaging operations. He still takes pictures, as does nearly every single person we talked to, both at Canon Inc. headquarters in Tokyo and the Utsunomiya factory. Canon runs internal photography competitions for its employees, and as you can imagine, the competition is stiff.

There is also a consistent understanding throughout Canon that photography matters. The company is perhaps best known for its professional equipment, but what arguably matters even more are the millions of people who use Canon gear to document their lives and all the precious moments therein.

Birthdays, first steps, graduations, and all the everyday joys dotted along the meandering paths and intersections in life are captured on cameras. There’s little doubt Canon would love for everyone to use its cameras, but the company nonetheless understands that the very concept of photography itself is eminently powerful, regardless of brand.

Ultimately, before any work on any camera or lens begins, the company’s love for photography is a foundational essential ingredient to its products, from entry-level to professional. There is no Canon camera or lens without this grounding principle: Work in the service of photography.

The Canon Design Concept: Chasing Perfection Through Persistence

The core design of the Canon T90 that Mr. Tokura worked on has influenced nearly every Canon EOS camera for almost 40 years. The position of the shutter release, the command dial arrangement, and the overall curves and aesthetic of many of EOS cameras trace a clear line back to the 1980s.

To a cynic, this consistency may seem stale. However, the feel of a camera is one of the most significant differentiators these days. Canon insists that it is not tethered to the past and will never waver from changing things even if it upsets the status quo. However, there is a delicate balance here.

The refinements each model brings, although not universally for the better — sorry, EOS R Multi-function Bar — are very thoughtful. The prototyping process is extensive, with Canon making models by hand and using advanced 3D printing to test the feel of each new product. The camera must fit perfectly, and the buttons and dials need to be in the optimal location for the target user.

No detail is too small, either. Take the Canon EOS R1’s new grip design, for example. When prototyping this, although it’s possible to digitally place the pattern onto the mold as data, Canon’s team deliberately chose to transfer it using traditional etching techniques. Each pattern placement is visually inspected and manually adjusted to ensure precision.

![]()

Another example is the pattern of each ring on Canon RF lenses. Zoom, focus, aperture, and control rings all have their own carefully considered texture, allowing photographers to immediately know which dial they’re touching without looking.

As Haruki Ota of the Canon Design Center explains, Canon employs a human-centric design philosophy. Cameras and lenses must always be comfortable to hold and use. When designing for a diverse group of people who use their cameras in different ways for various purposes, this is an exceptionally challenging target to hit.

Some of the most impactful design choices may come easily, while others require consistent, regular tinkering. In either case, whether it’s an obviously good idea or one that took extensive effort, the core part remains: just as many people are involved with what happens inside the camera, a significant number are concerned with the exterior, and it all matters considerably. The camera and lens are the tools that photographers use to realize their creative vision, whether it’s for fun or to make a living. When shaping tools like that, every detail is important.

![]()

Core Features and Functions

There is admittedly a certain satisfaction in using a camera that requires effort to capture a good shot, but Canon’s focus on making photography more accessible undoubtedly has broader appeal. From its image stabilization technology to more recent AI-powered image processing, the company is committed to making it easier for more people to capture the photo they envisioned when they pressed the shutter.

Dual Pixel CMOS AF

Many recent advancements in camera technology focus on making it easier to capture the desired image, with a significant part of that effort coming from autofocus technology.

Back in the film SLR and later digital SLR days, autofocus technology was relatively archaic. We have gone from a handful of heavily centralized autofocus points to thousands arrayed across the entire image area. Cameras have evolved from sluggish, pulsing autofocus to lightning-quick focus that locks onto a subject so quickly it feels like the camera has read your mind.

Although a photographer’s skills and expertise still matter and make capturing an excellent, sharp image easier, autofocus technology in modern Canon cameras is so good that it can sometimes feel like cheating. These improvements are hard-earned and require constant, dedicated work.

One of the most interesting stops on our tour at Canon’s headquarters in Tokyo was in a long hallway-like room tucked away in an auxiliary building. Here, an extensive motorized track launches a subject toward a camera, and Canon’s engineers have complete control over the lighting and speed, ensuring they can test autofocus performance with carefully chosen parameters.

During one demo, Canon technicians launched a photo of a lion toward the camera. I mean launched. If it were a real lion, and I was behind that camera, I’d be convinced I was a split-second from a horrific death. The camera stayed locked onto the eye in the print, even when a Canon employee dimmed the lights to mimic dawn and dusk conditions.

Another demonstration focused on the Action Priority autofocus in the Canon EOS R5 Mark II and EOS R1. This mode currently works for soccer, basketball, and volleyball, making it easier to capture sharp shots of high-tempo, exciting events in each sport, like a header in soccer or a spike at the net in volleyball.

Building these modes requires extensive field testing and real-world work from many photographers, including professionals brought in by Canon to help test new modes and products. Canon said during the presentation that it captured hundreds of thousands of photos of each sport to develop the Action Priority feature. That’s a lot of kicks, dunks, and spikes — and a staggering amount of time. And ultimately, most EOS R5 Mark II owners will never photograph these sports at a professional level, but that granular work ensures that for those who do, they nail the shot nearly every time.

While the demonstrations were impressive in and of themselves, what impressed me most was that this performance resulted from years of evolution across many aspects of the camera. These aspects include the image sensor itself, meticulously coded algorithms, improved processors, and the motors inside the telephoto lens attached to the camera. Every incremental improvement is built on decades of work by countless people.

Koichi Fukuda, Canon’s top engineer and Senior Principal Engineer of the IMG Development Unit, explained that Canon’s celebrated Dual Pixel AF focuses on three key areas: intelligence, speed, and precision. The company’s Dual Pixel AF enables advancements in all three areas and is one of Canon’s most distinct technological advantages over its peers.

![]()

Many aspects of modern Canon EOS R mirrorless cameras are leaps and bounds better than those in previous generations, but perhaps no single area of progress has transformed the way photographers take pictures more than autofocus.

Image Processing

Another area of significant focus is image processing. We’ve already discussed how improved processing impacts things like autofocus, but it also affects image quality.

As Kenji Takahashi from Canon’s IMG Development Unit explained, a significant area of focus for Canon’s image processing engineers is to work diligently to help photographers capture the images that they imagine when they press the shutter. There’s a lot of work that goes on behind the scenes inside the camera to make subtle, essentially imperceptible changes to how the camera renders colors and selects the appropriate white balance when using AWB, which most photographers utilize, especially when they capture RAW images.

Recent developments using deep learning help modern Canon cameras detect the subject and lighting conditions to improve automatic white balance. For example, consider scenes with blue skies. In these cases, if the camera tries to select a white balance to balance the entire scene, the blue sky will appear faded and less saturated, and non-sky areas will appear disproportionately warm. So thanks to deep learning, Canon’s AWB system can ignore the blue sky when selecting the correct white balance for a complex scene.

Similarly, deep learning is also used to detect plant areas in photos. Rather than balance the entire scene, including green plants, the camera can recognize that the green is truly meant to be green and is not excessively tinted.

It’s also possible to select the correct white balance while taking into account people in the frame. This is especially important when capturing portraits, as sometimes the “best” white balance setting for the overall scene can lead to inaccurate skin tones, which is, of course, not the desired outcome when photographing people.

As of now, all these deep learning-based area detection features are only in Canon’s most advanced cameras, including the recent EOS R1 and R5 Mark II models. However, face-area detection has been utilized in many Canon cameras for well over a decade.

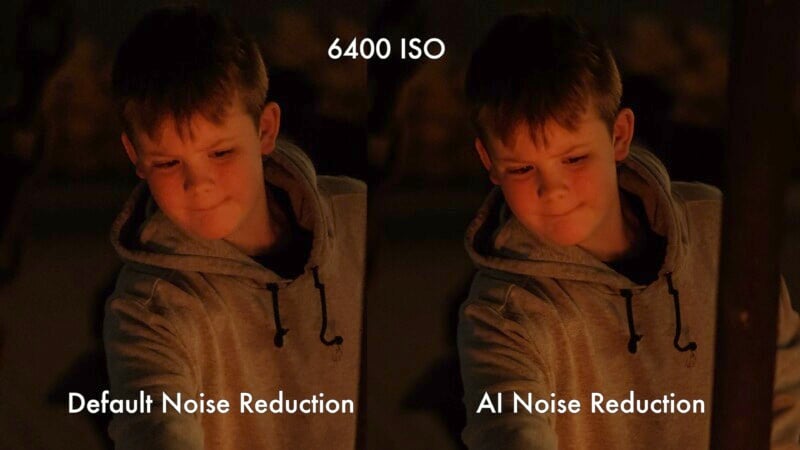

Recent advancements in image processing focus on enhancing sharpness and reducing noise. Canon’s optical engineers work exceptionally hard to get the best possible image quality. However, when combined with software, it is possible to achieve even better results. Canon’s image processing engineers work on building neutral network lens optimizers, which are trained using many photos captured with various lenses to precisely correct for various aberrations, including diffraction.

This is an area where, perhaps more than any other, Canon combines its physical camera and lens technology with groundbreaking AI to help photographers realize their vision without ever compromising their creative vision. After all, it is one thing to improve image quality and camera performance using AI, but another matter altogether to fundamentally change how a camera captures a scene.

Reliability: Canon Breaks Its Cameras So Hopefully You Won’t

A fascinating (and briefly uncomfortable stop) on the Canon headquarters tour took us to the company’s reliability and camera testing facility. Here, Yoshiyuki Kaizu showed how Canon tests the ruggedness of its cameras. Professionals need their cameras and lenses to work as expected all the time, not just when conditions are comfortable.

We went into Canon’s climate-controlled testing rooms. One has temperatures well at around 120°F, the humidity feels like it’s at 100%, which proved significantly more uncomfortable for me than for Canon’s professional camera gear. The next stop was a subzero room, which, after the horrors of the wet, hot room, felt downright refreshing. For a minute, at least, and then it was excruciating.

In extreme environments, which go far beyond the typical conditions most photographers will ever encounter, engineers test camera responsiveness, image sensor performance, and handling. While I wouldn’t want to spend much time in either room, the cameras didn’t skip a beat.

A more common scenario for photographers is dropping their camera, and Canon focuses extensively on this as well. We saw Canon’s drop and impact testing machines, and quite frankly, it was tough to watch Canon cameras and lenses being violently shaken and dropped. Having dropped some gear over the years, including a dreaded tripod fall on a mountainside many years ago, I’m grateful for the people at photo companies who work day in and day out to make equipment more durable, even if some cameras in a lab have to pay the price.

No photo gear can survive every fall; it is just not a practical or achievable goal. However, for Kaizu’s team, the goal is to do everything possible to ensure that as few photographers as possible break their gear. That also includes engineering the best possible boxes and packaging for shipping gear to distributors and customers. Having seen how major shipping companies handle boxes, this might be the most critical reliability work of all.

A Camera’s Glass Eye: The Lenses

While cameras are, of course, essential to the image-making process, so too are the lenses. Many photographers are more excited by new camera models, but those after my own heart go wild for glass. The camera captures the vital light, but that light would never get there without the lens. An immense amount of work goes into designing and shaping glass so that lenses focus light optimally before it strikes the image sensor.

Optical Advancements Years in the Making Are Still Crafted by Hand

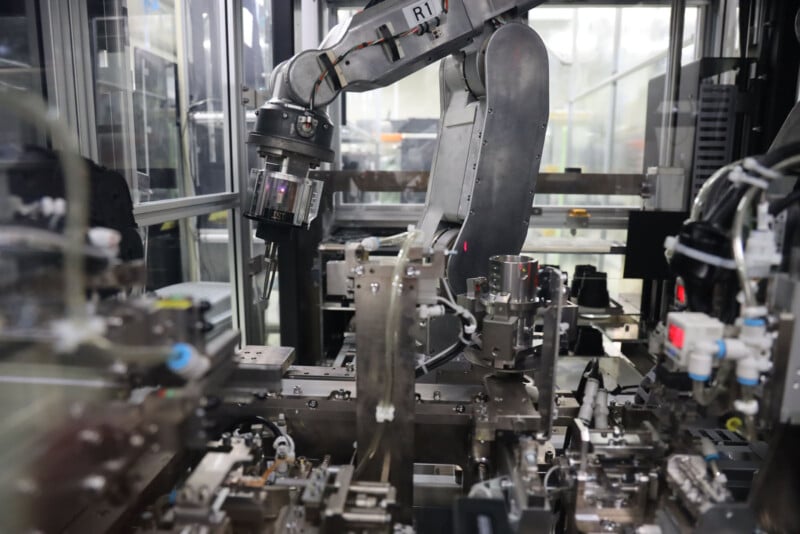

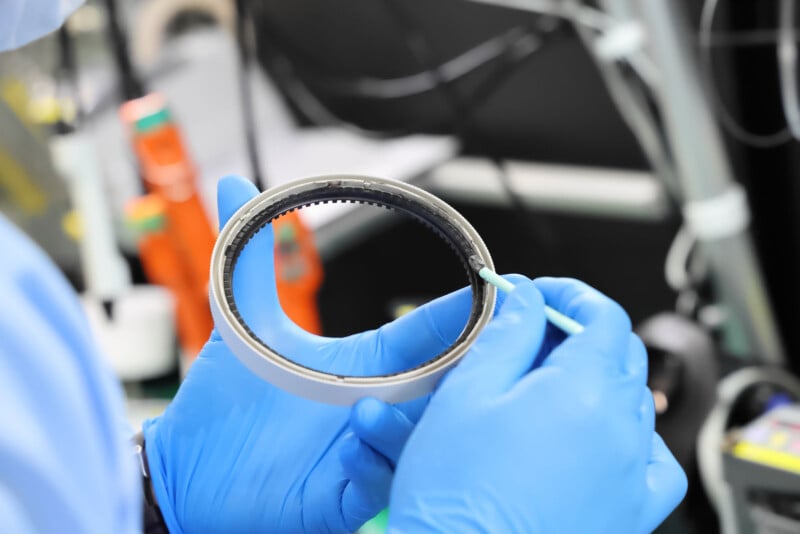

Glass technology has come a long way in recent years, especially when it comes to molding weird and wild aspherical lenses. While machines shape some of these complex elements, the most sophisticated of all are hand-ground by Canon’s most gifted artisans: Takumi.

These veteran craftsmen and craftswomen train for many years, and if they reach the level of master, or “Meister,” they even earn special badges on their uniforms. The ultra-high precision components that the Takumi make by hand are vital for Canon’s best lenses, including perhaps the company’s most impressive telephoto zoom lens ever, the RF100-300mm F2.8 L IS USM.

It is striking that in an industry where so many things are made by machines — I did also see robots assembling lenses, by the way — there are still essential pieces of glass that are formed by the weathered hands of master artisans. Canon states that human hands are still far more sensitive and precise than any machine, and when working on lenses requiring nanometer-level precision, the human touch is irreplaceable.

While the optical designs may still be engineered on computers by brilliant mathematical minds, many of Canon’s best lenses still rely heavily on analog, human touch, and Canon believes this may always be true. The company is training new generations of Takumi all the time.

Optical Specialties

At Canon’s Utsunomiya factory, I saw two very different sides of the same “optical technologies” coin. On the one hand, Canon engineers work diligently to develop electrical and mechanical technologies to improve a lens’s stabilization and autofocus. On the other hand, optical physics still rule the day. However, for photographers, both these very different types of engineering must come together and work in perfect harmony. You need exceptional glass for photos to be sharp and free of aberrations. But you need the electronics and mechanics to drive the autofocus, keep everything stable, and encase the sophisticated glass in a way that is useful.

While Canon has made countless optical and mechanical advancements for its EF and now RF glass over the decades, perhaps the most impressive is the company’s BR optical elements. These glass elements, a decade in the making, incorporate anomalous dispersion characteristics that change how blue light is refracted inside the lens. The BR element is super-thin, barely perceptible. However, this ultra-thin element, sandwiched between concave and convex elements, changes how blue wavelengths of light focus on the image sensor.

Compared to traditional elements, BR optics help blue light focus at the same exact location as red and green light. This means significantly reduced longitudinal chromatic aberrations (LoCA). Canon is adamant that no other company has technology as good as its BR lens.

The company is similarly proud of its SWC and ASC optics that reduce ghosting and flare. SWC, or subwavelength structure coating, puts 300nm wedge shapes on the surface of the glass to reduce internal reflections.

Lens Autofocus

On the mechanical side, it’s impossible to entirely separate improvements in lens autofocus motors from better AF systems inside cameras, but there is no doubting the impact that faster and more powerful autofocus motors in lenses have on overall performance.

Within Canon’s RF lens lineup, there are five types of actuators used to drive autofocus, each with distinct advantages. The Nano USM motor, perhaps the most impressive of the bunch, is tiny, quiet, and quick. It is used in many professional Canon zoom lenses.

![]()

The high thrust VCM is swift, too, and used in Canon’s series of five hybrid prime lenses, including the new RF 85mm f/1.4L VCM.

Then there’s the lead screw type STM system, which is compact and quiet, too. This is best used in compact, lightweight lenses like the RF 10-20mm f/4L IS STM ultra-wide zoom lens.

The gear type STM is a bit more old-school, but it still has a place in modern RF lenses because it offers good thrust at a reasonable cost. It is used in prime lenses like the RF 28mm f/2.8 STM.

Finally, rounding out the list is Canon’s ring USM autofocus system. This is a high-speed, high-thrust autofocus system used in the company’s super-telephoto lenses like the RF 400mm f/2.8L IS USM. When power is the priority, this is the pick.

It should perhaps go without saying by this point, but there are many people behind each of these autofocus actuators, and Canon is constantly exploring new options.

How Canon’s Culture Connects With Japan

Alongside the insightful tours and presentations at Canon HQ in Tokyo and the Utsunomiya factory, Canon also went above and beyond to share Japanese culture with us.

This was a significant focus throughout the week, and included local cuisine, a wonderful day in Kyoto, and even sumo wrestling. While obviously Canon wanted to show its guests a good time, the desire everyone had to showcase Japanese culture, history, and customs with us was clearly sincere. Some of our experiences were captured in our RF 85mm f/1.4L VCM Review, which we shot in Japan using Canon’s broader series of VCM hybrid lenses.

Canon’s products and technologies are impossible to separate from where they’re made, and are deeply connected to the people who make them. While new cameras and lenses are exciting to photographers like me, they come and go over the years. The people who work on Canon photography equipment persist through all the technological evolution and photo industry upheaval. Ultimately, more than anything else, the people will also be what I remember and value most from my time in Tokyo visiting Canon. Photography is ultimately not about megapixels, but about connections.

![]()

There Are No Small Parts When It Comes to Making Your Photos a Reality

While each Canon imaging technology I learned about in greater detail from the people behind it was fascinating, I was most struck by the number of people involved. Canon explains that one of its biggest strengths is the in-house development of much of its technology, and that relies on a vast number of people.

Every photographer has had the experience of opening up a new or new-to-them camera for the first time. It’s a magical feeling because cameras are more than just cameras. They’re how we capture life, enjoy our free time, or, for the especially fortunate and skilled, put food on the table.

But what many photographers, myself included, rarely think about are the people along the way who make your camera. I don’t just mean the hundreds of people across dozens of teams who developed or manufactured a specific camera model, but the thousands more who came before them whose work echoes through the decades. That applies equally to lenses, and perhaps even more so because strong, reliable optical foundations have existed far longer than digital photography was even a twinkle in anyone’s eye.

![]()

Thanks to my experiences at Canon’s Tokyo headquarters and its lens factory in Utsunomiya, every time I press the shutter on my camera, I will be cognizant of the fact that many talented, passionate people poured years of hard work into it. While modern mirrorless cameras are sophisticated digital machines, they are still ultimately made by people who, in many cases, love photography just as much as you or I do.

Image credits: Chris Niccolls, Jeremy Gray, Jaron Schneider, and Canon