80 Years On, The Photos of the Hiroshima Bombing Still Shock

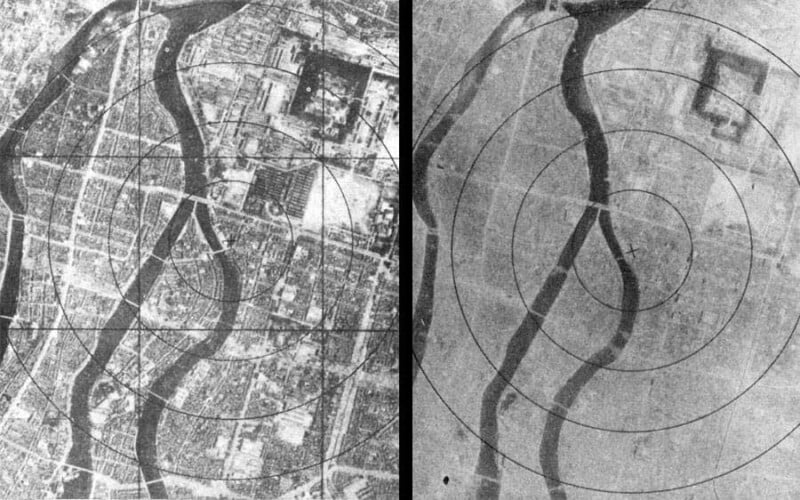

Eighty years ago on August 6, 1945, the Enola Gay aircraft dropped a 9,000-pound uranium-235 bomb named ‘Little Boy’ on the city of Hiroshima — devastating it and the lives of hundreds of thousands.

Also flying with the Enola Gay that day was a Boeing B-29-45-MO Superfortress named Necessary Evil, which flew for the purpose of taking photos of the historic event.

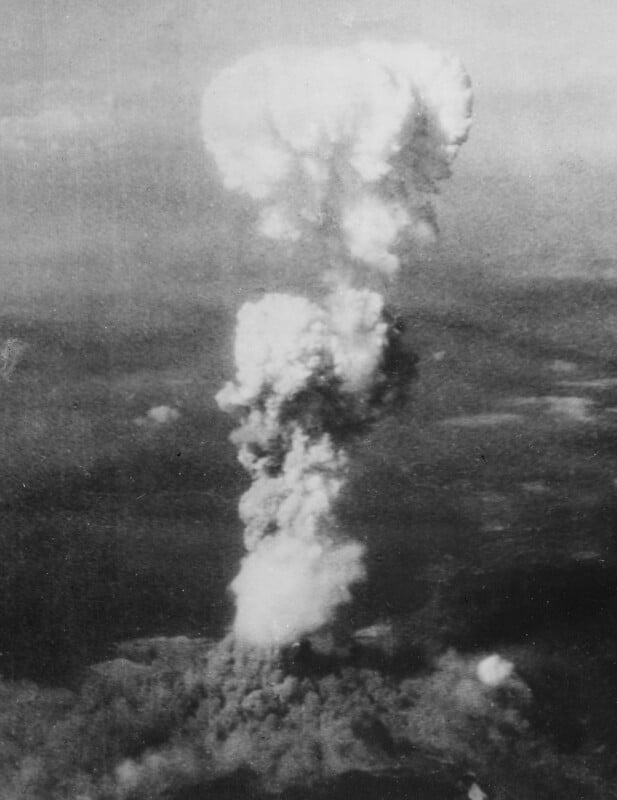

From the bowels of the Necessary Evil, Russell Gackenbach snapped photos of a mushroom cloud billowing 20,000 feet above Hiroshima. In a 2016 interview with Airman Magazine, which PetaPixel reported on, Gackenbach told what it was like to witness this event firsthand, and how it’s affected him years later.

“We did not know what type of bomb we had; did not know what type of blast to expect; did not know the effect of it,” Gackenbach said. “The only thing we were told was, ‘don’t fly through the cloud’.”

“We didn’t know what to say, or do, or anything,” Gackenbach said of the crew’s dumbstruck reaction to the bomb. “We made three turns around the cloud and headed home to Tinian. I did not hear the word atomic until the next day.”

Gackenbach captured two photos on his camera, which he claimed were the only two that show the start of the explosion. Other images of the bomb’s aftermath show the gigantic cloud still lingering three hours after detonation.

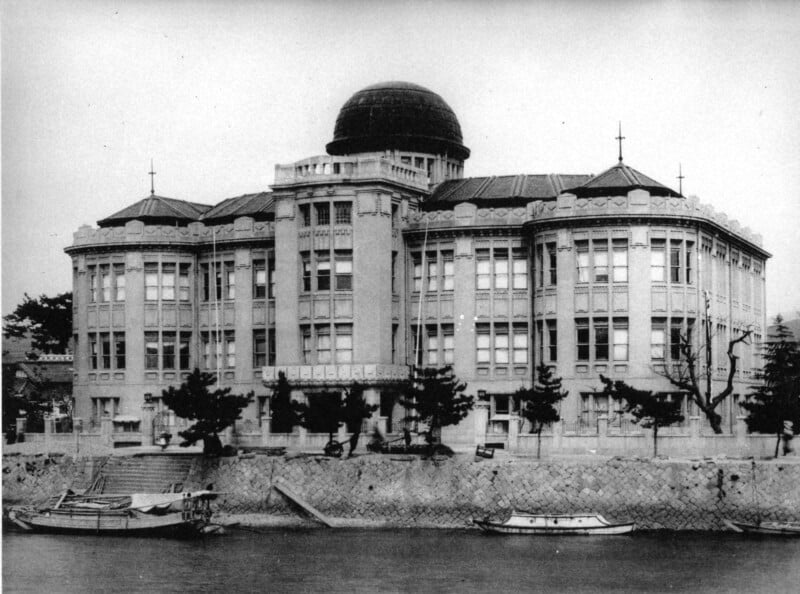

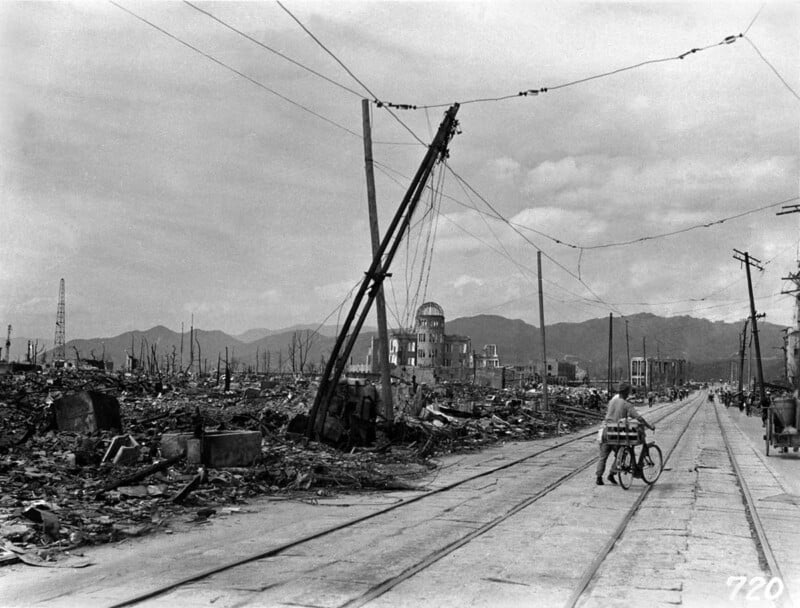

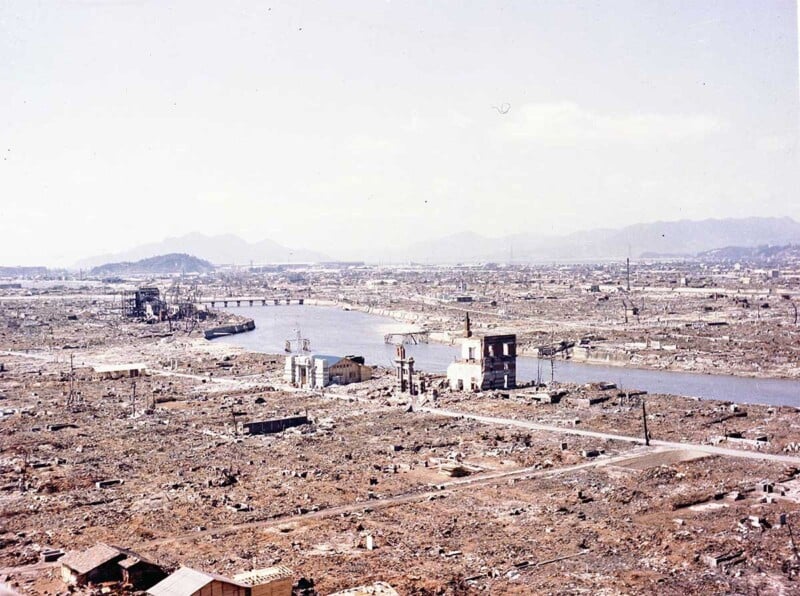

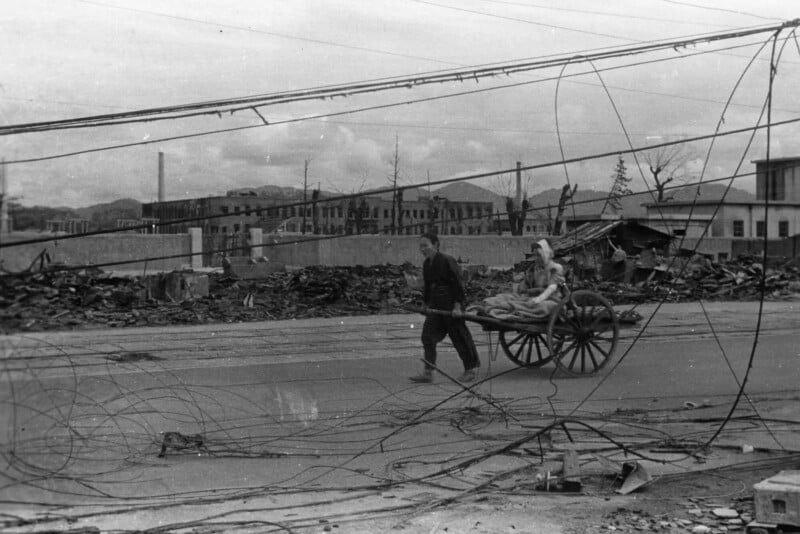

However, it is the photos taken on the ground that better capture the catastrophic impact of the A-bomb.

U.S. military photographers took images during occupation and documentation missions, which were restricted for a while.

Lieutenant Dan McGovern (seen below) was a cameraman for the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey that studied the impact. The airman recorded the realities of nuclear war, which included skulls and bones, teenagers suffering from radiation sickness, and a city in ruin. When he arrived back in the United States, he made secret copies of the footage so it wouldn’t be suppressed by authorities.

![]()

Many years later, a 1967 U.S. Congressional committee that included Robert Kennedy asked to see the atomic bomb footage. The material had been declassified but no one could find the originals. McGovern, by now a lieutenant colonel, directed the authorities to his copies.

McGovern’s clandestine copies shocked the world. In 1970 the general public got its first viewing of the footage that had been used in a film called Hiroshima Nagasaki – August 1945. When it premiered at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, a packed auditorium was stunned into silence by what they witnessed.