Break the Rules, Find Your Shot: An Adventure Photographer’s Guide

![]()

Pelican partner Boone Speed is regarded in many circles as a jack-of-all-trades. In addition to being a pioneering rock climber, Speed is also a successful photographer with a portfolio rich with unique images. His constantly shifting career path wound through graphic design and elite athleticism before landing behind the camera, giving him a unique eye for capturing the excitement of adventure and the lifestyle that comes with it.

Full disclosure: This article was brought to you by Pelican

At a Glance

While Boone Speed’s early years centered on climbing and graphic design, the pivot to photography wasn’t planned. Even winning a photo competition didn’t immediately spark a career change. “It still never even occurred to me to be a photographer,” he admits. “I always wanted to be a climber, and graphic design was the tool that let me get into the climbing industry.” However, after a decade in design, a change felt necessary. As his pro climbing evolved, documenting his travels ignited a new passion. “I realized that I really enjoyed using a camera to document the wild life I was living. And, I was pretty good at it.”

Speed’s design background fundamentally shaped his photographic eye. “I embraced every opportunity to break the rules,” he says. “Breaking the rules of photography gave me the look and feel that I was always chasing as a graphic designer.” He found inspiration in the gritty, alternative aesthetic of 1990s magazines like Ray Gun and Thrasher. “My photography is very graphics focused,” Speed explains. “Context matters. I’m trying to get to the essence of what I’m trying to capture. For me, simpler is always better.”

This unique style quickly led to high-demand commercial work for giants like Pelican and other major outdoor and athletic brands, before expanding beyond climbing and outdoor into architecture and product photography. However, relentless travel and campaigns led to burnout. “It began to feel like a grind,” Speed confesses. Feeling creatively drained, he stepped back from commercial work for nearly two years, finding renewed inspiration to create images for himself again during the sudden quiet created by the pandemic.“As most of us were going stir crazy, I started to feel the inspiration and I wanted to make images for myself again.”

Now, Speed operates with a renewed focus, choosing projects offering creative control. “I’ve wanted to stay a little bit out there ahead of the curve and do something unexpected,” he states. “My creative philosophy embraces calculated imperfection. My formula has always been let’s break some stuff and see what happens.” This might mean intentionally missing focus slightly or using slower shutter speeds to achieve a retro looking motion blur. “I want to make my images feel real, like they did back in those old music, surf, and skate magazines,” he describes. Drawing from these experiences, Speed offers PetaPixel readers tips for compelling adventure imagery.

Find Your Photographic ‘Why’: Defining Your Vision

For many aspiring photographers, the journey starts simply by capturing the world around them. However, Speed discovered that developing compelling work required more. “I quickly realized that telling dynamic stories through photographs often required me to dig deeper, asking myself not just what I wanted to shoot, but why,” he describes. He remembers his own path into photography wasn’t straightforward, rather, it emerged alongside his climbing and graphic design careers. He didn’t initially set out with a passion for taking photographs; his motivation stemmed from necessity.

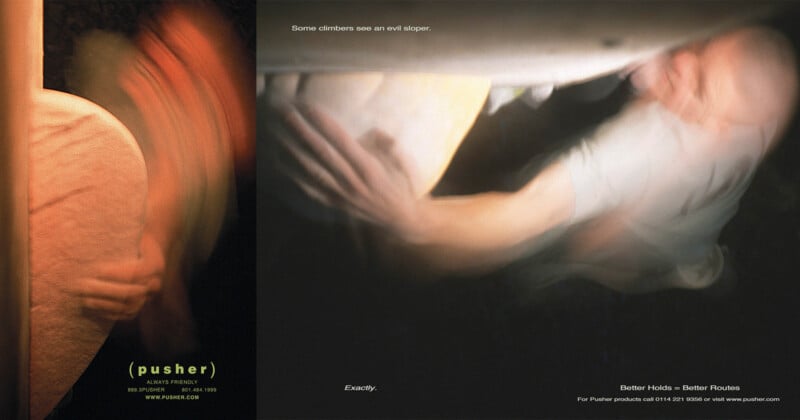

Speed recalls needing specific imagery for his climbing company, Pusher, at a time when that gritty, alternative aesthetic wasn’t common in the outdoor industry. “I had envisioned climbing marketing imagery that didn’t exist,” he explains. “So I had to teach myself how to use a camera and go out and make it.” This need became the driving force behind his entry into photography. “Since I really didn’t care what other people thought about my photography, I was able to just go out and make the images without any sort of pretense or need to be a great photographer. I just created what I felt.”

This ‘shoot what you feel’ approach was heavily influenced by the visual culture of the 1990s. “The raw energy of punk rock, the boundary-pushing graphic design of David Carson for Ray Gun magazine, evocative 60s and 70s album covers, and Richard Avedon’s rule-breaking portraiture all resonated with me,” Speed explains. “Even though I wasn’t a photographer at that time, those are the kinds of images that I was always drawn to,” he notes. “I saw a converging interest in out-of-the-box graphic design art and motion in photography and aimed to translate that feeling into my climbing shots.”

Speed suggests looking beyond just technical perfection. “When I first picked up a camera, it was because I needed to, not because I wanted to,” he says. “So, to not lose motivation, I had to quickly identify the feeling, style, or essence I wanted to convey. I was drawn to raw energy, quiet simplicity, graphic boldness, and nostalgic moods, all of which became my why. I started to want to be the creative mind behind the types of images I saw in those counterculture magazines that tugged at my raw emotions. Those images were far from perfect, which is why they made me feel something.”

Speed believes that understanding your why, the underlying visual style or emotion that excites you, provides a powerful compass. “It helps you make deliberate choices about composition, light, editing, and even subject matter, ultimately leading to images that are not just seen, but felt, and are uniquely yours,” he concludes.

Beyond Eye Level: Craft Unique Perspectives

Creating unique images sometimes means changing your point of view. For Speed, finding compelling perspectives involves keen observation and deliberate choices. “Even though I love letting a scene unfold naturally, I am always ready to capture it in the most compelling way possible,” he states. “While I am waiting for the scene to unfold, I’m considering all the different angles that can make the story more original and dynamic, so when the moment does come, I have a plan.”

One key technique Speed employs is using foreground elements, believing they can elevate a snapshot into a portfolio piece. “I like to add a little bit of mystery to a photo,” he explains. “Foregrounds can make viewers feel like they’re actually in the moment, witnessing the action unfold from behind a bush or a rock.” Technically, he favors specific choices to enhance this. “If I am going to use a foreground element, I want to shoot with a wide open aperture on a fast lens and get bokeh to blur it out,” he describes. This adds depth to the scene and also serves a practical purpose in commercial work by creating negative space. “That out of focus negative space gives you a place to put type,” Speed notes, adding value for potential licensing.

Speed’s climbing background hammered home the power of perspective. “It is incredible to see the exact same moment of a climber from two different angles,” he reflects. “If I take a photo from the side, the rock face might appear smaller and the landscape behind them would be the story. However, if I am above the climber, looking down with a wide angle lens, suddenly the viewer is transported to that space. They can feel the dizzying effects of hanging off a wall. It’s the same moment, but two completely different stories, all because of a shift in angle and perspective.”

Beyond physical positioning, Speed utilizes gear like tilt-shift lenses to creatively isolate subjects. He also experiments constantly with focal lengths, exploring different perspectives over his career, from wide angles early on to more recent work with telephotos. “When you are looking at those scenes in a telephoto, the compression adds a totally different story,” he observes. For Speed, finding unique angles isn’t a one-time trick, but a continuous exploration. “It is a lifetime of messing around, combining observation, technical skill, physical effort, and a desire to see the world differently.”

Light & Exposure – Capture What It Feels Like to Be In The Scene

While technical perfection in exposure is often pursued, for Speed, manipulating light is a tool to make the viewer truly feel the scene. His approach often prioritizes conveying emotion over strict rules, demonstrating how calculated imperfection can yield impactful images. “I like to play with exposure and angles that make the viewer feel what it was like to be in that moment,” Speed states. “I like my images to have authenticity and soul, and using light and exposure in unconventional ways can make that happen.”

Speed recalls a shoot in intense heat where conveying the feeling of baking sun was paramount. “It was blazing hot, so I made a creative choice that the photos needed to feel white hot,” he explains. “I wanted to overexpose the scene, so I exposed for the shade and let everything else blow out. And every time I was able to, I would use a closed aperture like f/16 to create a sunburst by shooting directly into the sun, which was a valuable way to convey the absurd heat.” This technique helped communicate the intensity of the environment.

While acknowledging the appeal of golden hour, Speed doesn’t limit himself. “I think every photographer loves low horizon light because it’s going to be a better technical photograph,” he admits. “However, a day consists of 24 hours, not just golden hours. I see potential in harsh midday sun or clouds to tell different stories. The challenge of making that ‘uninteresting’ light fit into the story is not only interesting to the viewer, but rewarding to me. It forces me to break the rules and think outside the box.”

One specific technique Speed uses to capture feeling involves slow shutter speed, particularly when shooting from a moving car. “Playing with light is a good reason to slow down your shutter speed,” he notes, having spent over a decade capturing blurred landscapes this way. “Capturing these slow shutter speed landscapes from a moving car puts my viewer in the scene. When you are driving 80 mph down a rural backroad, the scene out of the window isn’t sharp. It’s kind of a blur, and that’s how I want those pictures to feel.” By embracing techniques that prioritize making viewers feel, like intentional overexposure, varied lighting, or motion blur, Speed shows how creative use of light and exposure can immerse the viewer.

Seize the Moment: Adapting in the Field

Sometimes the most memorable photograph isn’t planned, but unfolds unexpectedly. For Speed, staying present, observing, and pivoting instantly is crucial. “While planning has its place, being ready to abandon the script and react to the moment is often where photographic magic happens,” Speed emphasizes. “It starts with paying attention. The observant part is seeing the opportunity.”

His iconic photograph, “The Leap of Faith,” featuring ex Cirque du Soleil dancer Shrikanta Barefoot in Yangshuo, China, perfectly illustrates Speed’s careful observation. The photographer wasn’t initially there for Barefoot. “I was on the wall shooting my friend and athlete Chris Sharma climbing as the golden light of dusk set in,” he recounts. “As the light faded, I looked down to see Shrikanta in the field performing his dance. I noticed immediately that he seemed to be in an almost meditative state.”

Positioned hundreds of feet away on the rock face, Speed recognized the potential but had to react fast. “I didn’t know if the scene would make for a great photograph, but I knew that I had to try,” he says. Constraints were significant: “I don’t know what his stamina is, and I’m running out of light so I have to make a call: Do I stay on this wall photographing Chris or do I rush down to capture this unique, organic moment?” He went for it, quickly rappelling down and changing lenses.

Critically, Speed prioritized preserving the moment’s authenticity. “What intrigued me was that he was doing this naturally. This wasn’t staged,” Speed explains. “I just wanted to remain a fly on the wall. I did not want to disrupt his mindset at all.” Lying low in the grass, he allowed Shrikanta to continue undisturbed. “He felt comfortable and safe and just kept his body moving. We didn’t say a single word to each other.” Working with dwindling backlight, Speed captured one of his most recognized works. “This is easily one of my favorite photographs, and it exists solely because I was aware and possessed the readiness to instantly shift focus and capture an entirely new story as it happened.”

From Crags to Clients: How Boone Speed Relies on Pelican

For a photographer like Pelican partner Boone Speed, whose work ranges from hanging off cliffs to navigating demanding commercial shoots, gear failure isn’t just inconvenient. “It can mean losing the unrepeatable shot,” he describes. His high-stakes career demands absolute confidence in equipment protection, a need Speed entrusts to Pelican. His philosophy is straightforward: “If I am checking any photography gear onto a plane, it’s going into a Pelican Air case, or I am leaving my gear at home. Those are the only two options,” he states unequivocally.

Pelican cases’ legendary durability is key, but for Speed, mobility is also crucial. “Luckily, Pelican has developed incredible cases that make traveling into remote locations easier,” he notes, specifically praising the AIR cases. “I love and use the Pelican Air cases almost full-time. They feel almost weightless when empty, but you can feel how unbelievably solid they are.” For Speed, this weight reduction is vital. “As a photographer who captures extreme athletes in extreme places, I need that blend of mobility and protection,” Speed emphasizes, echoing fellow Pelican user Benjamin Hardman who relies on Air cases in harsh arctic conditions. “The Air cases allow me to confidently pack what I need. Knowing my cameras and lenses are secure lets me focus entirely on getting the shot.”

Beyond dedicated camera protection, Speed utilizes Pelican’s TRVL series for general luggage. Offering a hybrid hard/soft shell design focused on lightweight durability, the Aegis line of rolling duffels, backpacks, and slings fit his needs as a traveling creative. “I’m really excited about this new TRVL line. It’s the best of both worlds,” he shares. “To have something insanely protective and yet, incredibly lightweight, is a game changer for photographers that travel. I appreciate that I can still feel like my valuable items not in my photography kit are protected from the unexpected.”

He highlights the practical benefit for frequent flyers: staying under airline weight limits. “Having luggage that feels protective, yet light, is crucial. To be able to securely pack a bunch of gear into a lightweight rolling duffel or backpack is vital.” Speed also values the design of the new TRVL line of products. “The Aegis backpacks and rolling duffles are stylish and look professional. I would have no reservations about walking into the MoMA with them, but they can also take a beating when I am using it in a rugged location.”

Whether facing saltwater spray on a boat, where Speed deems a watertight Pelican Air case essential, or the general wear of adventure travel, Pelican’s reliability is paramount. Like Martin Gregus, who trusted Pelican cases to protect his camera gear when his boat flooded while photographing polar bears in the arctic, Speed knows his gear is secure. Having the confidence that his valuable belongings are protected in both Pelican Air cases and the TRVL products allows Speed to fully immerse himself in the creative process, ready to capture those demanding, unrepeatable moments that define his work.

50 Photos To Give a Damn About

In today’s relentless flood of digital images, Speed understands it’s easy for photographers to feel pressured by quantity over quality. He encountered this when advising an aspiring photographer, offering simple guidance focused on building a meaningful body of work that matters to the artist. “Start taking one image a week that you care about,” Speed told him. “Then, the following week, aim to take one more, and continue to do so. At the end of the year, you have 52 images that you really care about, which is enough for a portfolio.”

To illustrate, Speed mentions a personal project that was sparked by that conversation. “I told him that, honestly, I have only taken like 50 photos in my life that I give a damn about,” he recalls. Seeing the young photographer’s disbelief spurred Speed to test his own theory. “He told me that he would love to see those 50 photos, so I decided right then to make that a project,” Speed says.

He dove into decades of archives. “As it turned out, I did have more than 50, I had about 1,400,” he admits. “However, since I started photographing in 1998 that averages out to a little more than one photo that I really give a damn about per week.” The exercise validated his core advice. “The exact number isn’t the point; the philosophy is,” Speed describes.

“Instead of chasing endless content, focus on intentional creation,” Speed explains. “Make it a goal to shoot just one image that you care about per week. Define what matters to you. Something that represents what story you want to tell.” Speed feels adopting this mindset shifts the focus from overwhelming volume to achievable, meaningful progress. “That’s an attainable goal for anybody,” he concludes. “At the end of the year, having 52 images that you truly give a damn about form a powerful and personal portfolio.”

Know Your Focal Lengths Before It’s Too Late

In the fast-paced world of adventure and athlete photography, Speed stresses that the decisive moment often allows only one chance to get the shot. This reality demands meticulous preparation, especially choosing the right lens before action happens. “There’s simply no room for error or hesitation when the stakes are high, as there aren’t a lot of second chances when it comes to working with extreme athletes,” Speed confirms.

Constraints like being roped up high on a cliff face photographing a climber reinforce this. “I don’t have the luxury of bringing another lens with me, let alone swapping, so I have to be fully confident in my lens selection before I climb,” Speed explains. This forces a crucial step in his process: pre-visualization. “I have to analyze my situation first and envision the shot that I want. What do I want that photograph to look like?” he asks himself, mentally running through options. “Is the scene calling for a standard zoom like a 24-70mm? Do I need the reach of a 70-200mm? Or is it a wider, 16-35mm useful to show the enormity of the scene? Knowing which lens I need before I take the shot is one of the most important aspects of my work.”

He recalls one shoot where this foresight was critical: capturing a Red Bull athlete performing a dangerous dirt bike jump. Knowing there’d be no do-overs, Speed had to pre-plan. “I had to analyze what I wanted. I had to envision the shot before I got in that position,” he says. “I wanted to make the jump look big and the rider small. To achieve this scale and feeling, I opted for an unconventional setup: a converted 17mm tilt-shift lens adapted to my medium format Fuji GFX, which is roughly a 12mm equivalent. The final photo has a totally different feel than if I had shot it with a 24mm, or even a 16mm lens.” That preparation paid off, allowing him to nail the shot on the only attempt. “Knowing your gear and envisioning the final image aren’t just helpful habits; they’re essential disciplines,” he concludes.

Context and Why It Matters

A single photograph has limitations, Speed observes. “It’s a silent, static frame,” he explains. For Speed, overcoming this to tell a compelling story often hinges on skillfully incorporating context. “Context is what transforms a simple picture into a narrative moment. I think the beauty of photography is that you have one frame to tell a story and I try to do that by capturing context,” he says. After all, as Speed points out, “My audience can’t read my mind. Effective context ensures that my photos have a distinct opinion or point of view and demonstrate a reverent sense of place.”

Sometimes, providing context means widening the frame to show the full picture. Speed recalls a Black Diamond photoshoot where a film was being made concurrently with the climbing. “I didn’t want to just take photos of the climbers, making it seem like they were alone,” he explains. “I wanted to tell the story about why we were there. This required including the surrounding activity and film crew. Sometimes I feel the need to use a wider lens, and capture more of everything to show the entire story.” Speed explains that including these behind-the-scenes elements provides crucial situational awareness for the viewer.

Speed notes that context can sometimes dictate a much tighter focus. He describes an Adidas campaign where evoking a brand connection was key, rather than a traditional portrait. “The images were really visceral,” he describes. “Basically, I made the campaign just images of the Adidas stripes in different settings, but that worked, because the three stripes are Adidas.” In this case, the brand was the essential context. “It’s not about the person wearing the clothes, it’s about the brand. The tight shot focused on the branding within a moment of authentic connection. I wanted the viewers to think simply, ‘that look is cool, I want that,’ which effectively told the intended story.” Understanding whether context lies in the broader environment or a specific detail allows Speed to choose the right approach to make his images resonate.

Beyond the Grind: Sustainable Creativity

The demanding nature of professional photography, with constant travel and client pressures, can easily lead to burnout, a challenge Pelican partner Boone Speed navigated firsthand. After years of high-profile work, he found himself feeling stuck. “I was working all the time, working myself to the bone,” Speed recalls. “I realized that I’d created my own trap by focusing only on rewards like money and success that can be fleeting and ultimately robbed me of the joy I had for the content I was shooting.”

To combat this, Speed actively diversified. “I have an entrepreneurial spirit,” he shares. “That led me to start a climbing product company and work as a brand advisor. These outlets allowed me to apply my creativity in new ways. I especially loved working on The North Face’s ‘Walls are Meant for Climbing’ program.” Speed notes simpler shifts in creativity help too. “Sometimes just deliberately switching up your subject matter, like exploring urban scenes with your camera after focusing on mountains, can be a powerful way to stay fresh.”

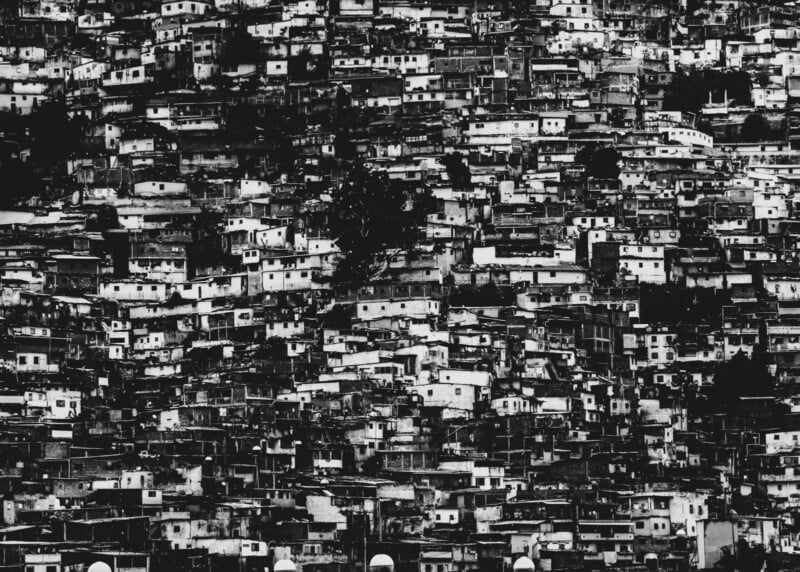

A crucial part of Speed’s inspiration to pick up his camera again involved consciously reconnecting with the “art” of photography itself. This meant returning to shooting for personal fulfillment. “Pivoting to using my creativity for new ventures helped me reconnect with the art of taking photographs. I’m back to loving photography and the process and taking pictures for me,” he shares. A major driver is his fine art practice, creating extreme high-resolution images for large-scale installations and murals with his partners at Flavor Paper. “This demanding work, requiring meticulous planning and patience for perfect conditions, provides deep creative satisfaction that I feel counteracts burnout,” he describes. “It doesn’t hurt that I am doing this by myself, which is a complete 180 degree change from the days of constantly working with athletes, models, and ad agencies.”

Ultimately, Speed advocates for a mindset shift, stressing experimentation and not taking the process too seriously. “For me, it’s about what the images I take feel like, and if I feel it, then it doesn’t seem like a grind,” he explains. He compares his approach to a musician exploring sound over technical perfection. “If I was a guitar player, I’m not Eddie Van Halen, I’m Lou Reed. I’m still just experimenting and I just want to make something that feels good and makes me happy. It’s easy to forget that when chaos begins, but I find it helpful to take a step back and remember that my 50 Photos That I Give a Damn About project only has an audience of one. Me.”

See more from Boone Speed on his website, Hence Creative, and Instagram.

Full disclosure: This article was brought to you by Pelican

Image credits: All photos by Boone Speed