Photographers Shouldn’t Fear Computational Photo Features

Computational photography features raise the hackles of many photographers, but many examples of these tools help photographers bring their creative visions to life and make their lives easier. That sounds good to me, not scary.

It’s fair to say there’s often a deep mistrust towards new technology in photography, which is somewhat of a paradox. Digital photography itself is a natural advancement of film photography; at some stage, an engineer would have presented the idea of pixels instead of film and would have probably come up against a fair amount of pushback. As an example of this mistrust, look at the way we talk about image editing; we question whether a frame has been ‘Photoshopped’ as if it’s a bad thing when in reality, pretty much every photo seen online has had some degree of enhancement, whether that be a healthy amount of adjustments in a RAW conversion software program such as Lightroom or even just adding a filter in Instagram.

The latest technology that is causing division among photographers is computational photography. This fairly broad umbrella term encompasses a number of functions that use computer-based processing to benefit your photography.

At one end of the spectrum, you could lump in-camera noise reduction into this sector, which sees the camera working to battle digital noise that can occur from high ISO values or long exposures.

At the other end, you have features such as High-Resolution mode, which typically works by firing off a burst of images and merging them in one frame that boasts a beefy resolution — much higher than the sensor could capture with just a single file. This mode can work with or without the camera being secured on a tripod and is particularly popular with photographers using the Micro Four Thirds system where resolution is limited — at present the highest resolution MFT cameras (Panasonic G9 II/GH7) offer 25-megapixels. While this High-Resolution mode has many benefits, including the ability to create bigger prints, there are drawbacks because while High-Resolution mode is suitable for static subjects such as landscapes and architecture, shooting sports or wildlife photography will be tricky in some situations thanks to fast-moving subjects changing positions in between the frames being captured.

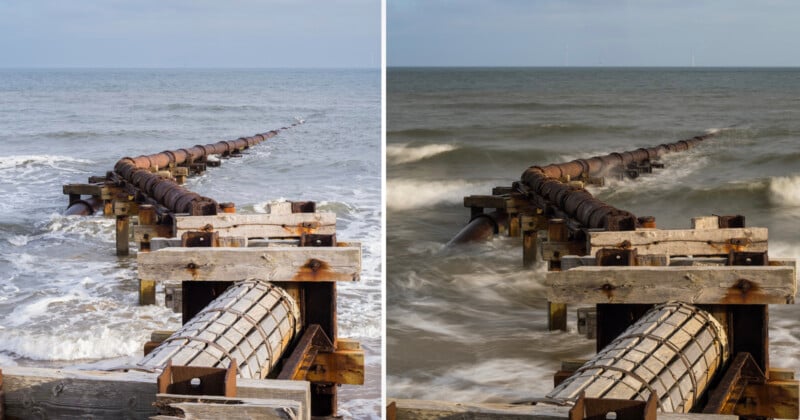

However, computational features are better associated with functions such as built-in digital neutral density (ND) filters. OM System’s Live ND is particularly mind-blowing, because not only will this feature enable you to artificially extend the shutter speed to capture a long exposure in stronger light environments where that would usually be impossible, but you can also see the effect coming together, and taking shape right before your eyes on the LCD, affording you more control to get that streaked sky or flowing waterfall looking exactly how you intended. More recently, attention on computational features has turned to a new function, and that’s the Live Graduated ND Filter mode found on the flagship OM System OM-1 Mark II, which as the name suggests, helps the photographer balance exposure levels in a scene by adding a Graduated ND filter effect to a chosen area of the frame — all completely in-camera.

Now, photographers invest a lot of time selecting the right filter system for their photography and plenty of hard-earned money buying the specialist optical glass, so there’s no surprise there would be a little skepticism when a digital version came along, but having used this technology myself, I see its potential. Having the ability to digitally balance the exposure level in the frame without needing to carry additional kit could be a huge win, not only for photographers looking to travel light, without the extra weight of filters and filter holders but also for photographers who are perhaps starting in genres such as landscape photography and don’t yet have the budget for often-expensive filters.

Of course, technology is only worth talking about if it actually works, otherwise it can be discarded as a gimmick. Well, OM System hit a home run with the Live Graduated ND filter feature on the OM-1 Mark II. With the ability to precisely select an area of the frame (and even the angle of the graduated area), the fine-tuning continues with the option to control the strength of the filtration and how hard the graduation appears.

Of course, the technology has its limitations; very high differences in light levels between a burning sky and a dark foreground may test the artificial filtration to its boundaries, but it should be remembered that this is just the start. As we’ve seen from advances in fields such as in-body image stabilization and subject-detection autofocus, these technologies tend to start small and then be improved upon very quickly.

While technology can be advanced, computational features will need more to become truly successful. They’ll need the acceptance and ‘buy-in’ from photographers who incorporate these features in their everyday workflow. This is when attitudes will change, and it’s my opinion that in just a few short years from now, computational features will not only have been accepted but expanded and advanced, with more ability to fine-tune exposure levels or reduce light pass-through to artificially extend exposure times to replicate the look of a 10 or even 20–stop ND filter.

Another huge factor that could not only help computational technology but also speed up its acceptance as a regularly used part of our cameras is the increasing emergence of AI. Imagine how AI could help the camera read a scene and automatically apply the correct levels of exposure correction to instantly balance the lighting in your frame. This is only the start; it’s time to embrace these computational functions and make them work for us, to help our photography, speed up our picture-taking, and help us capture even better photographs.