The Story Behind ReShark’s Inspiring Efforts to Save Zebra Sharks

ReShark is an international organization with partners in 15 countries, including 44 aquariums, raising endangered zebra sharks in captivity to release into the wild. The group hopes that it will be able to return the wild zebra shark population back to self-sustainable numbers.

Famed underwater photographers David Doubilet and Jennifer Hayes of Undersea Images were on the ground — and in the water — with ReShark as it released 500 baby sharks into the waters surrounding Indonesia. PetaPixel spoke with Doubilet about the incredible project.

‘Global First’ as ReShark Releases Captive-Bred Zebra Sharks

“This is a global first,” writes science writer Craig Welch for National Geographic. “While scientists often reintroduce rare captive animals on land — think California condors or giant pandas in China — nothing quite like this has ever been tried with sharks, which are disappearing around the world at an alarming clip.”

Beautiful, docile, and endangered, zebra sharks proved to be a great candidate for ReShark to test its ambitious initiative. “In recent years, zebra shark populations in Raja Ampat (West Papua province, Indonesia) have undergone dramatic declines in the wake of threats like habitat degradation and overharvesting due to shark finning,” explains ReShark.

“Due to a slow population growth rate, which is common for most shark species, conservation actions, including fisheries regulations and the creation of marine protected areas have not been sufficient for recovery of this species. Research and conservation planning have revealed that the species is unlikely to recover without additional intervention.”

The “additional intervention” includes flying zebra shark eggs from partner aquariums, like Sea Life Sydney Aquarium in Australia, to Indonesia where experts help the eggs hatch and raise the shark pups until they are ready to be released into the wild.

While zebra sharks are doing okay in some places, such as North Queensland, Australia, in Raja Ampat, 1,500 miles northwest of Queensland, researchers counted just three zebra sharks in a 20-year period with 15,000 hours of searching.

Raja Ampat has since created a shark sanctuary that is part of a network of nine marine protected areas. Despite these efforts, wild zebra shark populations have remained low, hence the need for intervention.

Photographers Doubilet and Hayes have worked in Indonesia’s Raja Ampat archipelago and were a perfect fit for working alongside Welch.

“National Geographic science writer Craig Welch and editor Anne Ferrar shared this story idea with Jennifer Hayes and me because we had worked in Raja Ampat waters and knew the place and the people. We burst with anticipation to work on this unique shark conservation project that is this simple: Put sharks back into protected areas where they can survive and thrive. What really stands out is the collaborative effort with 75-plus stakeholders from 15 countries. Jennifer and I have worked many years in Indonesian waters, where it was very rare to encounter sharks. To return to Kri Island and document the Raja Ampat Research Conservation Center shark nursery and witness the release of two zebra sharks into their future was something I never expected to do in my lifetime,” Doubilet explains.

A New Era for Wild Zebra Sharks in Indonesia

In January of this year, Nesha Ichida, an Indonesian marine scientist working for ReShark, held a 15-week-old zebra shark in a lagoon in the Raja Ampat archipelago.

“One of the strongest aspects of ReShark are the human stakeholders in the trenches making it happen: the scientists, aquarists, shark nannies, resort owners who built shark nurseries, program stewards, fundraisers, and a committed tribe working their hardest to put sharks back where they belong,” says photographer David Doubilet. “And ReShark is an opportunity to put a spotlight on aquariums that are often the subject of controversy — no aquariums, no zebra shark stock, no long-term data and genetics, no ReShark.”

The shark Ichida held, Charlie, named after a West Papuan provincial official who helped champion the ReShark project, was the first captive-raised zebra shark to be released in Indonesia’s protected waters.

“It’s such a milestone. This is such a hopeful, momentous moment,” said Ichida.

On hand to witness the release were a small crowd of government officials, indigenous Kawe villagers who manage the Wayag Islands region, and even some celebrity wildlife advocates, including famed actor Harrison Ford.

After a brief but optimistic speech, Ichida opened her hands and Charlie swam away off into a brave new world for zebra sharks.

“ReShark is hope for sharks that you can put your hands on. This program is not numbers on a spreadsheet or boundaries drawn on a chart, it is a contingent of people around the world contributing their expertise that results in zebra sharks released into prime habitat in protected waters,” Doubilet remarks.

A Shining Light in an Increasingly Dark World

Doubilet and Hayes have seen a lot throughout their careers — not all of it good.

“We have photographed the shark markets around the world, the largest in Vigo, Spain that supplies Europe. We left that assignment silent and darkened in spirit,” Doubilet tells PetaPixel.

However, working with ReShark “Illuminated a shark conservation reality we thought unthinkable until people like Dr. Mark Erdman at Conservation International saw a potential path and acted on it.”

“ReShark allows us to bring good news in a sea full of bad news,” Doubilet adds. “[That is] priceless in our time.”

Doubilet has spent five decades working alongside National Geographic to document the oceans.

“I thought I was documenting a world that was infinite but it turns out I was bearing witness to change and impact on this world hidden from our view,” he tells PetaPixel.

“The demand for shark fins has wiped out sharks across the world to such an extent they have become ghosts in the sea,” Doubilet laments.

“Large reef fish like groupers are few and far between, seagrass beds have vanished, and the most telling are coral reefs like the Great Barrier Reef that have endured sequential coral bleaching, creating silent coral cemeteries devoid of all life,” he adds, referencing that it is not only sharks who have suffered greatly in recent decades.

“My archive is really a window into oceans through the lens of time,” Doubilet says, which both underlies the importance of his work and reflects the devastation facing Earth’s oceans.

Passion for the Ocean Connects ReShark’s Dedicated Members and Photographers like Doubilet and Hayes

“For every assignment, I endeavor to create half-and-half images that share the surface world with the hidden world below. The surface of the ocean is the largest physical border on our planet, and I try to create a window to invite people into the sea,” Doubilet explains to PetaPixel.

One such half-and-half image for the ReShark story is Doubilet’s photo of Ichida releasing the zebra shark pup, Charlie, to his new life in the ocean. The photo, seen at the top of the article, is a brilliant reflection of people, place, and the power of conservation, Doubilet says.

“We definitely plan to follow ReShark’s efforts, and just maybe, we will encounter a released zebra shark in the future,” Doubilet says. “What joy that would bring.”

The Future of ReShark

Since releasing Charlie and his sibling, Kathryn, in January, Ichida and ReShark have released another zebra shark pup into the wild.

The ReShark team is contemplating what other shark populations may benefit from its hands-on approach. Perhaps angel sharks in the Canary Islands and the waters off the coast of Wales. Maybe nurse sharks in East Africa. Other candidates include non-shark species, such as bowmouth guitarfish or sawfishes.

Sadly, the list of species in need of help is endless. However, while the realities facing many species on Earth may be tragic, it is hard not to feel hopeful, thanks to the efforts of ReShark. Reintroduction will not cure all problems, but it will help, and every bit counts.

Erin Meyer, vice president of conservation programs and partnerships at the Seattle Aquarium, has been a crucial member of the effort to release sharks like Charlie and Kathryn into the wild, and she was on hand as Ichida released the first two pups into the water.

“I’m happy. And excited. And hopeful,” Meyer told Welch through flowing tears.

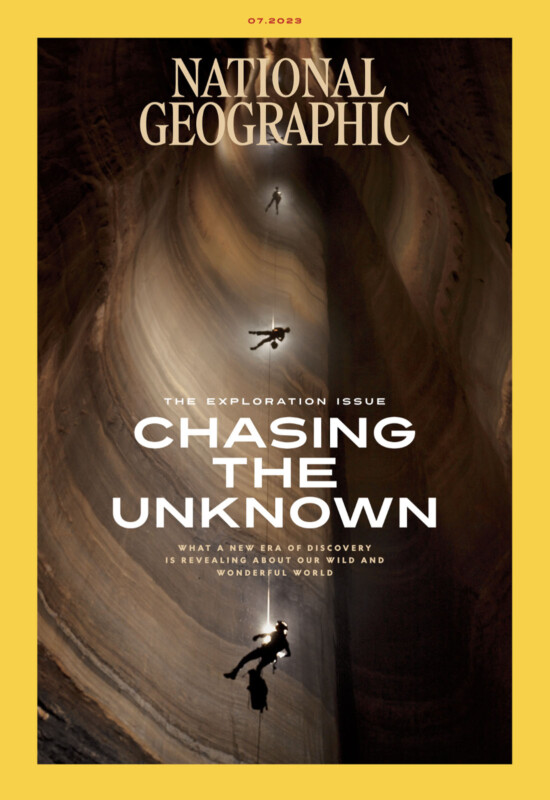

The full story, “500 baby sharks to be released: An exclusive look at an unprecedented mission,” is available on Natgeo.com and in the July 2023 issue of the National Geographic magazine.

Image credits: Photographs by David Doubilet and Jennifer Hayes, National Geographic. Additional photos and information are available on Natgeo.com and in National Geographic’s July 2023 issue.