Scientists Are Using Drone Cameras to Study the Ages of Dolphin Groups

![]()

Researchers in Hawaii are using drone cameras to study the ages of dolphins in free-ranging groups to better understand their populations and therefore better inform conservation efforts.

As reported by Kauai Now and in a research paper published in Ecology and Evolution, the scientists explain that understanding the population health status of long-lived and slow-reproducing species like dolphins is critical for managing conservation efforts. That said, traditional monitoring techniques that have been used to detect population-level changes can take decades. By that point, it might be too late to address problems.

“Early detection of the effects of environmental and anthropogenic stressors on vital rates would aid in forecasting changes in population dynamics and therefore inform management efforts,” the researchers explain. “Changes in vital rates strongly correlate with deviations in population growth, highlighting the need for novel approaches that can provide early warning signs of population decline.”

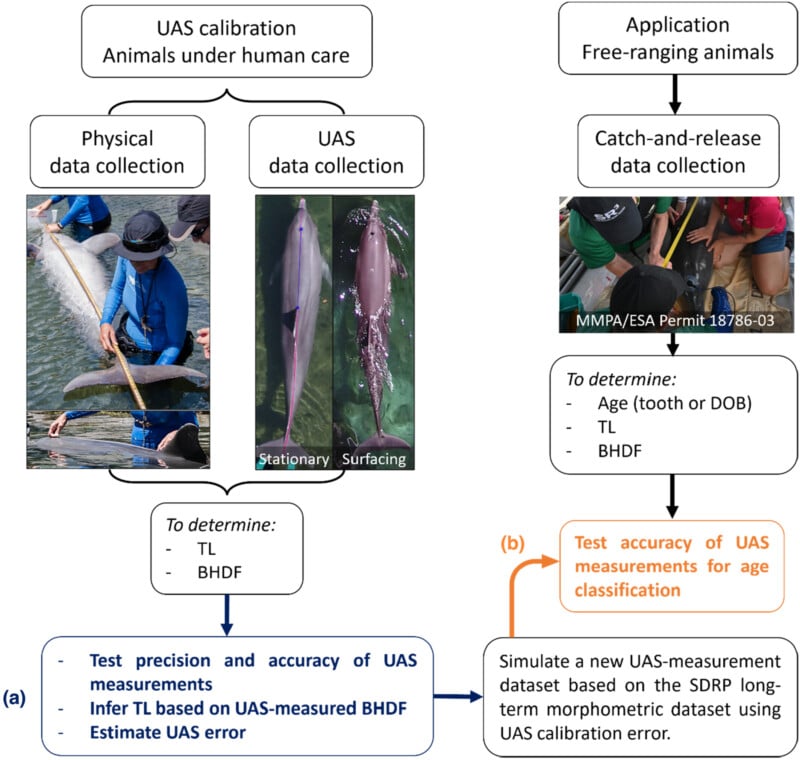

To get more up-to-date information, the scientists tried a novel method: using drone-base aerial photogrammetry to age-classify individuals by based on the total body length of bottlenose dolphins.

“Using a log-transformed linear model, we estimated TL using the blowhole to dorsal fin distance for surfacing animals. To test the performance of UAS photogrammetry to age-classify individuals, we then used length measurements from a 35-year dataset from a free-ranging bottlenose dolphin community to simulate UAS estimates of blowhole to dorsal fin distance and total body length,” the researchers say.

As Kauai Now explains, previous studies had documented encouraging results from using drone photography to study and measure the bodies of whales, but no similar approach had been tested on smaller creatures like dolphins. The researchers weren’t sure if it would work, but have been encouraged by the results.

“Our hope in developing and using this method is that we can quickly monitor the health of free-ranging dolphin populations,” Fabien Vivier, lead author of the study and marine biology doctoral candidate in the Marine Mammal Research Program at the University of Hawaii says.

“This may facilitate the detection of early signs of population changes, for example, a decrease in the number of calves, and provide important insights for timely management decisions.”

Image credits: Header photo licensed via Depositphotos.