Converting an Automatic Polaroid Pack Film Camera to Use Manual Exposure

![]()

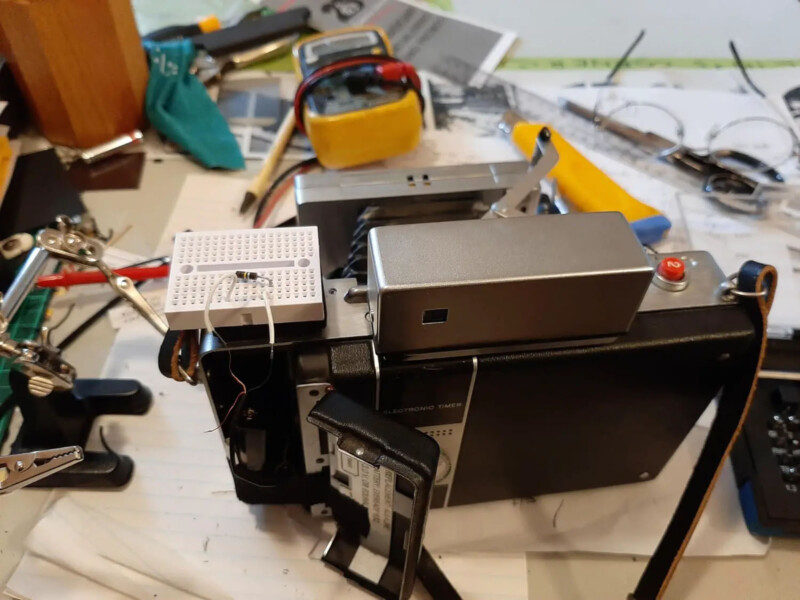

Photographer Jim Skelton is well known for his expansive collection of Polaroid cameras, dating back to the very first Polaroid Land cameras in 1963. Skelton aims to help photographers revive these automatic Polaroid pack film cameras to use manual shutter speeds and different film formats.

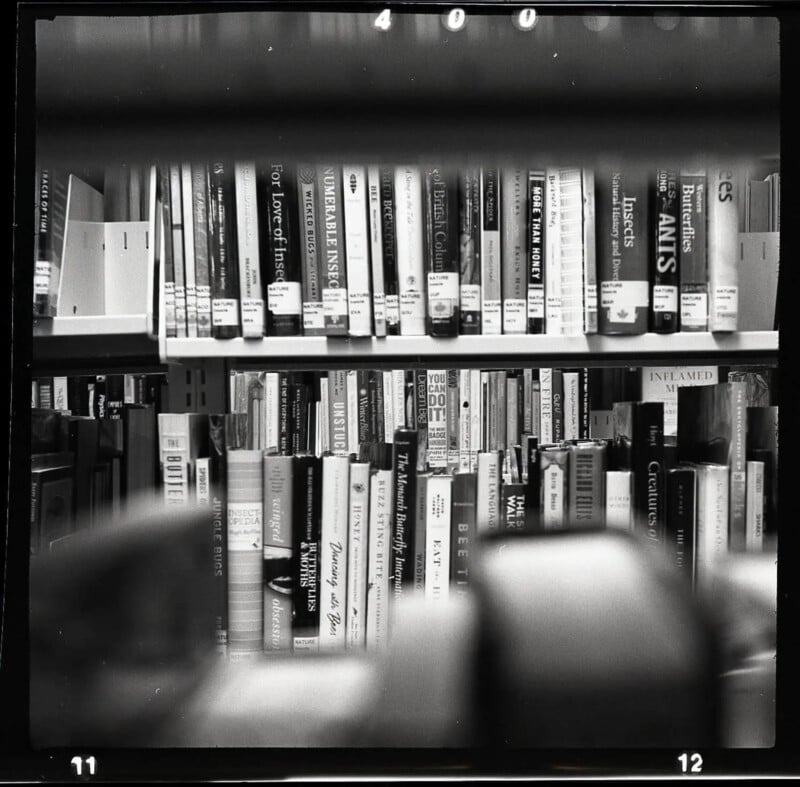

Pack cameras came under catastrophic threat in 2016 when Fujifilm produced its final run of pack film and dismantled its relevant manufacturing machines. While there are some ongoing efforts to revive pack film, Skelton’s conservation approach relies upon converting pack cameras to use other film formats that remain readily available.

![]()

Skelton also works to make these cameras more versatile and useful to photographers, including by inexpensively turning them into manual exposure cameras rather than the automatic exposure cameras they were when they hit stores in the 1960s.

On Skelton’s website, he delivers a detailed breakdown of how to turn an automatic Polaroid pack camera into a manual one.

“The shutter circuit appears quite simple on a Polaroid 450. I’m not an electronics engineer, but I know enough to understand that a photocell provides varying resistance depending on the amount of light that reaches it. If we can find out the resistance to shutter speed ratio, we can control the shutter speed by simply bypassing the electric eye and feeding the shutter circuit the resistance necessary for a particular shutter speed,” explains Skelton.

While he’s not the only person to develop a method for the conversion, his is relatively simple, requiring an “average person” to have “basic soldering skills.”

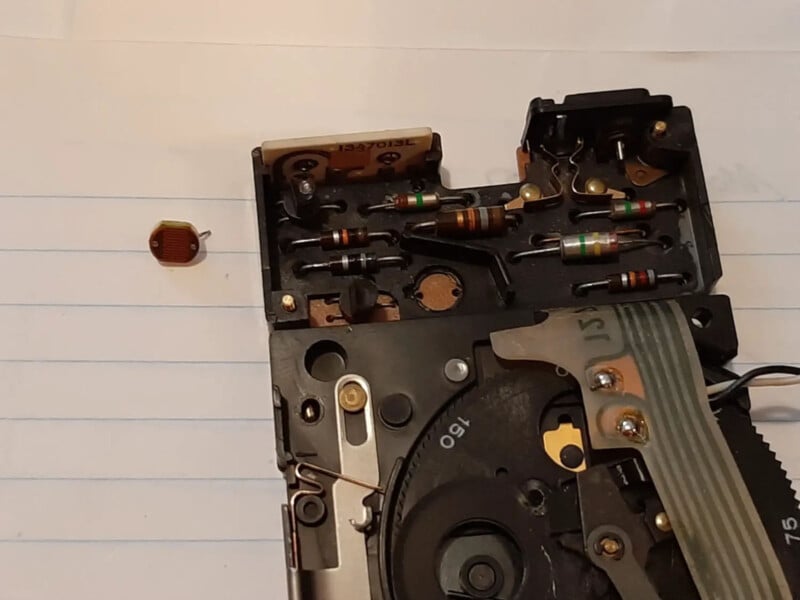

![]()

“The most difficult part is removing the electric eye and soldering wires in its place. It’s also a little tricky if you want to retain the option of an automatic shutter, which will involve bending a contact on the electric eye, soldering a lead to it, and replacing the electric eye,” Skelton says.

In an article for Emulsive, where PetaPixel first saw Skelton’s work, he writes, “I had in my possession a bunch of automatic cameras, so I got to thinking, ‘How hard would it be to give these wonderful cameras manual shutter speed capabilities?’ I’m not an electronics engineer or anything like that, but I did like to take stuff apart when I was a child…so, I figured that sort of qualified me to dive into this one.”

![]()

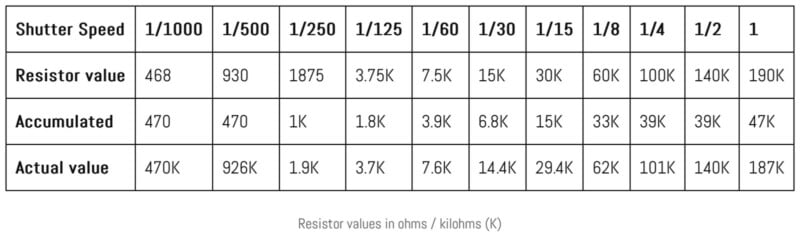

His article on Emulsive includes some of the same information as the instructive article on his site, but Skelton includes additional photos showing the process, plus a helpful chart that shows how different kiloohms correspond to different shutter speeds in a camera’s “open” and “closed” aperture modes. The kiloohm reflects resistance and different resistors produce varying shutter speeds.

Then Skelton wanted to figure out a way to create a camera that had manual shutter speed control but could still use automatic exposure. However, the issue of how to allow for swapping between these two methods of operation proved challenging, at least at first.

While MacBook Pro owners may complain about “dongles,” it turns out that a dongle saved the day for Skelton.

“Of course! I could make a dongle and plug it into the camera using a jack that automatically switched it from auto exposure to manual when the jack was plugged in!” says Skelton.

Skelton took it even further and 3D printed a container to put the interface with the resistor array required for manual shutter speed control. The box can attach to the Polaroid camera’s flash mount, plugging into a 2.5m jack that Skelton installed on the camera. When the array is plugged into the jack, the camera offers manual shutter speed control via the attached dongle. When it isn’t plugged in, the camera works as usual, with automatic exposure.

While many parts are involved, it’s actually an affordable conversion method. The 12-point switch, 11 resistors, 2.5mm jack, and 2.5mm plug cost about $10. Photographers will need some wire and solder, a soldering iron and access to a 3D printer to make the same dongle Skelton uses. However, that enclosure isn’t required.

“…You may age a bit under all the stress of modifying your camera, but it’s probably worth it!” Skelton exclaims.

“I hope that this might inspire others to see the potential in that old Polaroid discovered in Grandpa’s attic. Rather than giving it the toss, give it a chance with alternate film and manual shutter control!” Skelton says of his guide.

More of Skelton’s guides and photography are available on Instagram (professional and personal) and his website, Jim’s Polaroid Camera Collection.

Image credits: All images © Jim Skelton