A.I. Imagery Is Not Photography, It Never Will Be

![]()

We’ve all seen the images surfacing online of portraits with seven fingers on one hand and two left feet. Recently, the internet has been inundated by imagery coming from prompted artificial intelligence programs such as Midjourney, Jasper, and DALL-E. The world has been captivated by the potential these new neural networks bring to the creative space.

The word “photograph” was coined in 1839 by polymath Sir John Herschel. Remember him? The man who invented the photographic process using sensitized paper known as the cyanotype. All blueprints owe their creation to his brilliant discovery. It was Herschel who first used the terms photography, positive, and negative to refer to photographic images.

Why is this important? Because definitions matter. With every new technology, new terminology must be adopted to describe and explain what this new technology brings to the table. We all know about terms that surround the photographs we make regardless if they are analog or digital. Exposure times, f-stops, aperture, darkroom, and catch-light are just some examples of the words and phrases that surround our beloved process of capturing light.

Herschel based the word “photograph” on the Greek word ‘phos’, meaning ‘light’ and ‘graphe” meaning ‘drawing’. He wanted to describe the art of ‘drawing with light.’ Remember that modern photography traces its roots back to the camera obscura, a device labeled in the 17th century by the German astronomer Johannes Kepler. Even he thought that terminology mattered and went to great lengths to describe these new handheld devices and techniques. Kepler would later be honored by having a state-of-the-art space telescope named after him in 2009.

I am arguing that these digital A.I. images cannot be called photographs because at no point in the process is light used in their creation. For that matter, no photosensitive material or sensor is used either. You see, we analog photographers are in the same boat as the digital photographers for once. We can argue the merits of analog versus digital till the end of time, but on this topic, we should have a common concern.

I predict that these A.I. images will do to digital photography what digital photography did to analog photography some 30 years ago. In fact, I’ll argue that this new technology is more harmful to digital photography because the output of digital photography and A.I. images is the same: the JPEG, a series of ones and zeros in a long data file. We analog photographers will declare at least we have a negative or a print to show for it. This too, will not matter and all forms of photography will be tossed to the floor of the simulated and artificial darkroom. You see, nothing is safe.

It is not only photography that is under attack by this technology — writing and poetry have many concerns with ChatGPT the large language model. Teachers no longer can trust essays written by their students because there is no way to prove the source of the work. Music, as well, is being counterfeited and easily faked. Recently, a new song by JayZ was released on YouTube.

The song was composed, written, and performed by A.I. in the style of JayZ. JayZ had no say in the matter and only a trained listener could determine that it is not him singing on the track. Are we going to allow A.I. generated landscape photographs to come on the scene and win photography contests in the style of Ansel Adams? I say enough is enough.

There are plenty of examples where A.I. images pretend to be something they are not. Recently Boris Eldagsen submitted an A.I. image called ‘The Electrician’ to the 2023 Sony World Photography Awards (SWPA)—reputedly the world’s largest photography competition. To the surprise of many, the image won an award in the creative section. He offered to disqualify himself after he notified the organization that his submission was not a real photograph. The judges and promoters did not care and told him to keep the award. This does not sound good for my argument.

We also have the case where an A.I. image was submitted under the guise of photography to the Summer Photo Contest held by Digidirect in Australia. Jane Eykes won the top prize for such a submission and even fooled a photography expert in the process. Nobody suspected anything wrong with the submission. As we can see, this is not an isolated incident and this is going to become more commonplace.

Levi’s, the jeans company, which incidentally was founded just two years after the invention of wet plate photography in 1851, has reported they are going to “supplement human models” with A.I.-generated ones going forward for all their advertisements. We need to realize this type of image-making requires no models, no set, no make-up, no wardrobe, no camera, and finally, no photographer. Is it any wonder that for-profit corporations will embrace this new low-cost alternative over traditional forms of product photography?

There is also an intellectual property concern with these artificial intelligence image generators. You see, these neural networks are “trained” on immense amounts of text and visual data. Data that is taken directly from the internet without the permission of anyone who created the information in the first place. This data includes billions of photographs.

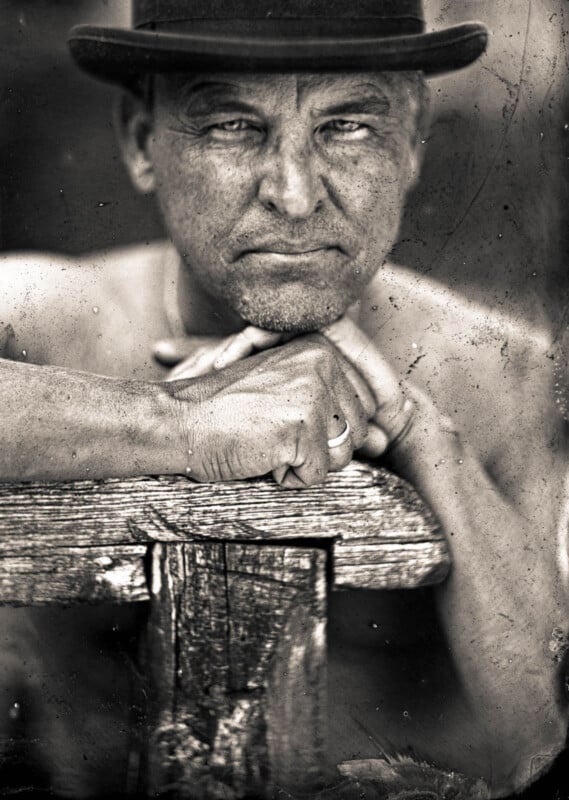

As a photographer who specializes in portraiture, I find it troubling that the output from these A.I. systems is nothing more than stolen imagery from other photographers melded together to give us a portrait of a person who has never existed. Is this how creativity should work? The consuming and regurgitation of someone else’s work? The bigger question is, who is going to buy and hang on their wall a portrait of a person who never was? As I write this, I find myself asking more questions than I am answering. This is where we find ourselves as photographers in 2023.

Why is this important? The painting below by famous Austrian-Irish visual artist Gottfried Helnwein looks like a photograph, but it can never be called one because paint and a brush were used to create it. Terminology is important to avoid confusion. A.I. work is anything but a photograph. If we don’t have agreed-upon definitions, you’ll have paintings winning photography contests. Well heck, why not submit a sculpture to a photography contest while we are at it? The truth about the origin and method is important.

So, what can be done? For starters, we can insist that such images not be called photographs. I know this is difficult. I searched Instagram for #aiphotography and found 178,585 posts. We can ask the artists and the industry that is using and developing this new technology to come up with their own appropriate terms and descriptions. Like the recent NFT craze, nobody knew what a Non-Fungible Token was before the technology arrived on the scene.

A.I. artists need to develop their own terminology just like our good friend Sir Herschel did 170 years ago. Using the word “photography” to describe these works is a misnomer, pure and simple. I’ve seen the use of the term “fauxtography” being thrown around. But it’s usually used in a derogatory manner by a photographer. I’ve put some thought into this question and I came up with “Prompted Artificial Graphic Design (PAGD).” Maybe a simpler “A.I. Art”?

There is hope. We are already seeing some changes to the rules that govern photography contests. The New Zealand Institute of Professional Photography just released a call for entries for their annual iris awards sponsored by Sony. All submissions must include ‘original capture’ RAW files. Which A.I. photographers will never be able to supply. In fact, it is impossible to know which images the A.I. confiscated and used to generate their output.

So, where does that leave us? Hopefully this new fascinating technology can find its own way in the world on its own merits. It should not ride on the coattails of photographers that have honed their skills for over a century and a half. Intent, method, and provenance of creation, are paramount for any piece of art.

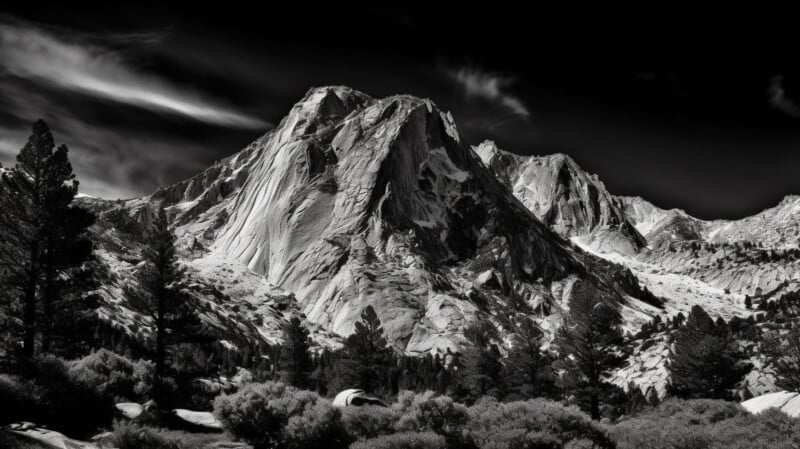

I’ve always thought that photography is a record of reality. In a pure sense, it is about capturing light at a specific time in history, a permanent record of what was at that moment. Any person who has ever pointed a camera at a subject understands that composition and light cannot be described with words. We must use our eyes to see what is before us. We all ride on the backs of the men and women who practiced photography before us. From Niepce to Daguerre, to Archer, to Eastman to Steve Sasson. We owe it to them to protect the meaning of what it is to take a photograph.

I think that Beaumont Newhall from the George Eastman Museum (1948-1971) said it best:

Neither words nor the most detailed painting can evoke a moment of vanished time as powerfully and as completely as a good photographic record. The camera records what is focused upon the ground glass. If we had been there we would have seen it so. We could have touched it, counted the pebbles, noted the wrinkles, no more no less. The photograph takes infinite care and renders its illusions perfect. The implicit faith and truth in a photographic record.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.

About the author: Shane Balkowitsch is a wet plate collodion photographer. He has been practicing for over a decade the historic process given to the world by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851. He does not own a digital camera and analog is all that he knows. He has original plates at 64 museums around the globe including the Smithsonian, Library of Congress, The Pitt Rivers Museum at the University of Oxford, and the Royal Photographic Society in the United Kingdom. He is constantly promoting the merits of analog photography to anyone who will listen. His life’s work is “Northern Plains Native Americans: A Modern Wet Plate Perspective” a journey to capture 1,000 Native Americans in the present day in the historic process.