Meyer Optik 35mm f/2.8 Trioplan II Review: Bokeh is Front and Center

![]()

The Meyer Optik Görlitz 35mm f/2.8 Trioplan II is a unique lens that performs its best when the bokeh is specifically integrated into a shot and not just a coincidence of the defocus area. That means it’s not for everyone, but it has its place.

A special thank you to Lensrentals for providing the Nikon Z7 II used in this review. The company’s complete list of available gear for rental and sale can be perused on its website. Personal note: the yearly subscription for Lensrentals HD is well worth it if you rent more than four or so times a year.

The Meyer Optik Görlitz brand doesn’t have the most sterling reputation. While the name itself dates back 126 years when optician Hugo Meyer and businessman Heinrich Schätze founded Optisch-Mechanische Industrie-Anstalt Hugo Meyer & Co. in Görlitz — at the time, a town in the Kingdom of Prussia, a lot has changed.

As we’ve noted in prior coverage, in 1920, the company began working with former Zeiss developer Paul Rudolph. In 1990, after spinning off of a relationship with VEB Carl Zeiss, the company was unable to attract investors and liquidated. It came back in 2014 through the new brand manager Globell B.V. who bought the name and exhibited new lenses. By 2018, the company collapsed despite raising over $600,000 in Kickstarter, and everyone who backed the lens projects lost their money.

![]()

However, in August of 2021, Meyer Optik — now known as Meyer Optik Görlitz GmbH and based in Bad Kreuznach — proclaimed that after “almost three years of hard and intensive work,” it was now an independent company that was “ready to step out of the shadows” with an expanded portfolio of lenses based on classic designs. At the time, I commended the company for owning the faults of the prior management — corporate transparency is an unfortunately rare occurrence in our modern capitalist economy.

Since then, the company has successfully developed (and delivered) seven lenses, ranging in focal length from the Lydith 30/3.5 II to the Trioplan 100/2.8 II. The company seems to have reclaimed its integrity and proven itself worthy of carrying the historic brand, which became imminently clear in my discussions with representatives.

So, let’s see what the German company has brought us with the Meyer Optik Görlitz 35/2.8 Trioplan II.

Build and Ergonomics

Author’s Note: The Meyer Optik Görlitz 35mm f/2.8 Trioplan II is available in Canon EF, Canon RF, Fujifilm X, Leica L, Leica M, M42, Micro Four Thirds, Nikon F, Nikon Z, Pentax K, and Sony E mounts. Unfortunately, the Leica M mount version is not rangefinder coupled, so you must either zone-focus or use live-view/EVF (if available).

![]()

For this review, I used the Nikon Z mount version of the Meyer Optik Görlitz 35mm f/2.8 Trioplan II, which due to the Z mount’s very short flange distance, is the longest version available at 78mm (3.07 inches). By comparison, the Nikon F mount variant is only 52mm (2.05 inches) in length. If you use multiple systems or want to ensure compatibility in the future, go with the Nikon F mount. With an appropriate adapter, it will fit anything from Canon EF to any mirrorless camera, though it will not easily adapt to Pentax K or M42.

Weight comes in 300 grams (10.6 ounces) — again, other versions will be a little lighter to varying degrees depending on the mount. The filter thread is 52mm, so it’s a reasonably petite lens.

![]()

The lens feels very solid, which is the first thing I noticed after I removed it from one of the most admirable display cases I have ever seen for a lens. The housing is black anodized aluminum; everything is metal except for the front and rear caps. I am told that all of the mechanics are sourced in Germany from precision suppliers who also produce parts for Zeiss and Leica, while Meyer Optik produces the optics in Bad Kreuznach, and assembly is done by hand in Hamburg. Every lens is cleaned, assembled, calibrated, justified, and inspected for quality control by hand.

There isn’t much I can complain about here. The aperture ring, located at the front of the barrel, is clickless, which is not my preference, but at least it has more than sufficient damping to ensure accidental adjustments don’t occur. I never had a problem with it, but I prefer click-stops for a quick adjustment without looking at the lens. I imagine video-centric shooters will like it, however.

![]()

The focus ring is exceptionally smooth with just the right amount of resistance; it’s possible to focus it with one finger but damped enough that precise adjustments are a cinch. The focus throw is about 300 degrees — five feet to infinity is covered in about 30 degrees, which is reasonable for a relatively wide f/2.8 optic. The lens has a very impressive 0.29x magnification (1:3.5), so most of the throw is in the last two feet or so.

The diaphragm’s twelve aperture blades remain virtually perfectly circular until about f/5.6, where the iris takes on a polygonal shape. I quite like the shape, but I know many people prefer very rounded blades at all apertures. Either way, given the fairly wide focal length, it’s not bound to be an issue.

![]()

Overall, there is not much to critique. I would have liked to see contacts for EXIF data, focus confirmation, and open-aperture metering, but this is more of an issue for DSLRs than mirrorless cameras. Either way, remember to set your non-CPU lens data in the camera if it has IBIS.

Optical Design

Like all of Meyer Optik’s lenses, the Trioplan 35 is based on a very old design — well, sort of. While lenses like the Lydith 30mm or Biotar 58mm have a direct vintage analog from which they inherit their optical design, there has never been a 35mm Trioplan. And there is an excellent reason for this.

![]()

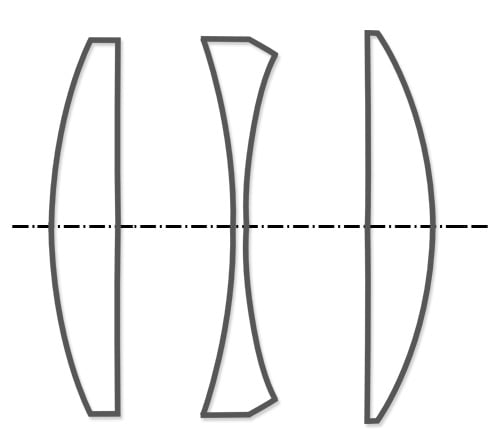

Keep in mind that, despite my review lens having a Nikon Z mount, the overall lens is a DSLR design — the Nikon F, Canon EF, and other SLR mount options are optically identical. This means the traditional trioplan designs — such as the 50/2.8 and 100/2.8, upon which the Trioplan 35 design is based — are easily accomplished with just three elements because of their longer focal lengths.

The problem comes when you try to widen that focal length below the necessary back-focus distance, which is well above 35mm for a DSLR mount. To accomplish this, it becomes essential to create a retrofocus (also known as “reverse telephoto”) lens. Meyer Optik wanted to keep the storied trioplan look, so the design was slightly modified instead of creating something completely new.

Meyer Optik appears to have accomplished this by adding a sizeable negative meniscus (convex-concave) widely spaced from a thick converging (positive) biconvex lens in front of the traditional triplet configuration. In doing so, it was able to produce a 35mm asymmetric lens successfully — allowing for a shorter focal length than the back-focus distance. The result is a five-element/five-group design; the stop appears to be located between the fourth and fifth elements.

This design is pretty typical of early retrofocus lenses — the front negative lens widens the field of view, and the large spacing from the negative member and positive rear member allows for a resultant positive power. The concave surface of the first element, in combination with the thick converging second member, enhances relative illuminance (i.e., reduces vignetting), lessens distortion, and lowers the Petzval sum (field curvature).

The triplet group in the rear — derived from the Trioplan 50mm and Trioplan 100mm — comprises three elements in three groups. The first (positive) and second (negative) elements correct for axial chromatic aberration, while the separation of the second and third (positive) elements allows for further correction of the Petzval sum. The triplet configuration offers six degrees of freedom (each element has two air-glass surfaces). It can balance all third-order aberrations by tuning the radius of curvature for each surface.

Image Quality

Author’s Note: All images are presented without any corrections applied.

The Trioplan 35 isn’t exactly a lens designed with optical perfection in mind, nor do I think it should be reviewed that way. This is a “character” lens — whether that appeals to you or not, only you can say.

I was surprisingly impressed with the lens in many ways.

![]()

![]()

At first, I was alarmed that the lens wasn’t supplied with a hood. My concerns were soon abated because flare resistance is, frankly, remarkable, especially given the high number of air-to-glass surfaces. Try as I might, I simply could not get this lens to flare in any objectionable way. I assume the small front element has a lot to do with this, along with what are certainly some excellent coatings.

Vignetting is nigh on nonexistent (remember, this lens has no contacts, so there is no in-camera correction at work, nor any in post), which is surprising due to the small front element. The moderate f/2.8 maximum aperture keeps this at bay, I assume. Similarly, there is practically zero distortion, which indicates the power of the front negative element is relatively low.

Field curvature is present, but only at closer focusing distances. I doubt anyone intends to use this for flat-field close-up work, so this is a non-issue.

Lateral and axial chromatic aberration are very well-controlled — clearly, Meyer Optik put some work into fine-tuning the element radii to correct for this. There are traces of purple fringing if you look closely, as well as some light longitudinal (axial) CA at the closest focusing distances in certain situations. Still, it’s rarely an issue, if it’s even noticeable.

![]()

![]()

The Trioplan 35 features remarkably close focus — almost 1:3 magnification — which, paired with the moderately wide-angle field of view, allows for some exciting perspectives. In fact, I’d say that this is one of the best features of the lens; bokeh can take on an almost painterly look while still being deep enough not to obliterate most of the subject in a wall of blur.

![]()

So far, so good, right? Well, there is one niggle, which may be an issue depending on how you intend to use this lens. While the optical configuration has done an excellent job of balancing other third-order aberrations, spherical aberration (SA) has the potential to be overwhelming.

A type of monochromatic aberration, SA presents as a sort of “blooming” or “glow,” almost as though you’ve put a strong Tiffen ProMist filter on the lens. This is caused by peripheral light rays that don’t converge at the same point as those in the center — essentially, not all of the light focuses at the same point on the sensor as it would in a theoretically perfect lens. The result is a massive reduction in apparent resolution and microcontrast over the entire image and point light sources (e.g., a street lamp or lighted sign) blooming heavily.

![]()

This isn’t all bad, though, and I think I understand why Meyer Optik has designed the lens the way it has. Spherical aberration seems slightly over-corrected at close-focus distances; however, the image is overwhelmed with SA at infinity. What I think is happening here is that as you focus to infinity, the lens increases the distance between the third element — which is the first (positive) lens in the rear triplet group — and the fourth and fifth members (last two elements of the triplet). This distance affects SA control and essentially causes the lens to move from over-correction through neutral correction and into under-correction.

Why? There are several reasons, in my mind.

Firstly, the trioplan design is known for its classic “soap bubble” look, caused by the over-correction of spherical aberration. However, with a relatively wide angle of 35mm and a modest f/2.8 aperture, you won’t get much of that pronounced soap-bubble bokeh except at closer distances.

![]()

Secondly, for portraiture, slight under-correction of spherical aberration tends to be more pleasing — this is why some of the most highly-regarded portrait lenses have fewer aspherical elements or lack them entirely (ASPH elements result in better optical correction, but harsher bokeh).

![]()

Thirdly, spherical aberration clears up very quickly upon stopping down, where the lens becomes remarkably sharp. This means if you want to use the lens for landscapes (meaning near-infinity or infinity focus), you can easily stop down (as you likely would anyway) and have no problems.

I suspect that the neutral correction of SA is somewhere around one meter, simply because the soap bubble look at the closest distances is not quite as overwhelming as it is on some of Meyer Optik’s other lenses and images in that range have fairly ordinary (but still pleasing) bokeh but almost no SA. Of course, part of this is because of the 35mm focal length and moderate f-stop.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A Unique Character Lens Done Well

Personally, I have come to like what Meyer Optik has done here. At first, I was pretty off-put by the excessive SA at far distances, but it made sense after shooting the lens at various focus distances and viewing the images.

This is much more of a “Swiss Army” lens than others in Meyer Optik’s catalog — you can use it up close for that unique bokeh, at portrait distances for its pleasant rendering, or the furthest distances stopped down for landscape work. It’s less of a specialist lens and more of a generalist lens, but still with plenty of the singular charm that has come to define the Meyer Optik brand.

The key to this lens is to shoot in a way that makes the bokeh an essential part of the image and not just blurred background. The lens can turn what would otherwise be a blasé photo into something painterly, almost like a Millet pastel or William Turner watercolor. But it requires a specific and different approach, one that I certainly haven’t come close to mastering; that has never been my style, but it’s something I’d love to continue to explore.

Unlike some of Meyer Optik’s other lenses, where there are vintage analogs (upon which the newer lenses are based) that you can pick up on the used market, this lens is unique.

Are There Alternatives?

Nope, not really. There are plenty of vintage 35mm f/2.8 lenses (the Contax Zeiss 35/2.8 and Leica 35/2.8 Summaron are personal favorites), but none with the incredible flare resistance, near zero distortion and vignetting, excellent chromatic aberration control, high magnification, and unmistakable rendering that this lens offers. If you use it right — which takes some practice — the results are singular.

Should You Buy It?

Yes, if it sounds like something it suits your photography or is something you want to experiment with, the Meyer Optik Görlitz 35mm f/2.8 Trioplan II is a great addition to your kit. It’s best if you intend to make use of the potential the lens offers: particularly the characteristic bokeh and interesting perspective (due to the wider field of view) at near-focus distances.