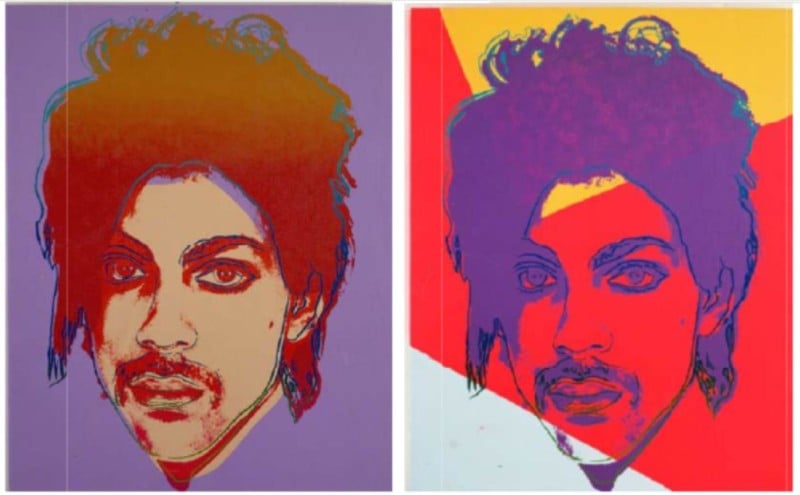

U.S. Copyright Office Argues Warhol’s Use of Prince Photo Was Not ‘Fair Use’

![]()

The United States Copyright Office has submitted an opinion to the Supreme Court that argues Andy Warhol’s use of Lynn Goldsmith’s photo of Prince was not fair use, sharing sentiments with opinions sent by the NPPA and ASMP.

On March 29, 2021, the New York-based U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals found that the Prince Series of artwork created by Warhol was not transformative enough and ruled that it violated photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s copyright — overruling the original verdict. The Andy Warhol Foundation appealed that decision to the United States Supreme Court.

In March of 2022, the Supreme Court announced it planned to hear The Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith case in October. The ultimate ruling then will have a massive impact on the visual arts community with regard to fair use.

Yesterday marked the last day that amicus briefs for the case could be submitted to the Supreme Court. As explained by the Cornell Law School, amicus briefs come from a person or group who is not a party to an action, but has a strong interest in the matter and will submit an argument that, usually, is intended to influence a court’s decision. Sometimes, final judgments will reference opinions that were sent to the court through an amicus brief.

Submitting an amicus brief to the Supreme Court is far more involved than doing so for lower courts, and anyone who goes through the trouble of submitting one does so under the presumption that the court, or at the very least its clerks, will read it.

There are many amicus briefs that have been submitted for this case, but two stand out as particularly important. The first is one submitted by Mickey Osterreicher and Alicia Calzada of the National Press Photographer’s Association (NPPA), Thomas Maddrey of the American Society of Media Photographers (ASMP), and Stephen Doniger of Doniger/Burroughs PC which sides with Goldsmith and argues that Warhol’s use of her photo was not fair use and that the judgment of the lower court, which found in favor of Goldsmith, should be upheld.

“The fair use defense was never meant to give infringers a pass so long as they claim some new subjective “meaning or message” in their derivative use regardless of how it is used, and neither this Court’s prior holdings nor common sense support that position. Rather, any purported new meaning or message is only relevant in the context of a qualitatively different purpose or use than that of the original,” the NPPA and ASMP argue.

“The role of the creative community in this country cannot be overstated. The depth and breadth of these creators surpass their collective output and contribute immeasurably to the understanding of our world. Almost nothing in our lives is untouched by the professional creativity of photographers like Goldsmith and the many other skilled writers, sculptors, painters, graphic designers, illustrators, musicians, screenwriters, poets, choreographers who act as both an economic engine and a cultural touchstone in society. These individuals, many represented by amici, are watching this case closely as their livelihood depends on it.”

While the NPPA and ASMP’s support is important, another amicus brief was submitted that is particularly notable: one from the United States Copyright Office. In it, the Copyright Office says that copyright matters, including those of fair use, are of particular importance to it and the U.S. government as a whole.

“The question presented implicates the expertise and responsibilities of other federal agencies and components as well. The United States therefore has a substantial interest in the Court’s disposition of this case,” the amicus brief reads.

“Copyright law encourages the creation and dissemination of expressive works by granting copyright holders exclusive rights to the fruits of their creative endeavors, while preserving breathing room for secondary uses. The fair-use doctrine is an important element of this statutory balance.”

The Copyright Office takes the same stance as the NPPA and the ASMP: the judgment of the court of appeals that found in favor of Goldsmith should be affirmed.

As mentioned, the Supreme Court will see many amicus briefs sent to them on cases, but when a U.S. government entity, like the Copyright Office, sends one, it is very likely that the Supreme Court will pay particular attention. As a result, the U.S. Government’s support of Goldsmith is hugely influential.

The Supreme Court is asked to review many cases and only accepts a small number of them. The fact it agreed to hear this particular case means that it has something to say about it, but what that will be won’t be clear until October. What is clear is that whatever the court decides will be extremely important for the interpretation of copyright law and fair use.