Satellite Imagery Reveals Antarctic Ice Loss is Double Previous Estimates

New research on Antarctica found in two separate studies that reference multiple optical and radar satellite sensors has revealed that the ice loss in Antarctica is much worse than previous estimates.

Two studies that investigated calving — the term that describes the breaking off of chunks of ice from the edge of a glacier — found that the crumbling ice in Antarctica is actually double that of previous estimates and details how the continent is changing. The two studies were led by researchers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California and reveal what NASA says is “unexpected” new data about how the Antarctic Ice Sheet has been losing mass in recent decades.

The first study, published in Nature and titled Antarctic calving loss rivals ice-shelf thinning, maps how iceberg calving has changed the coastline of the polar continent over the last 25 years.

“Antarctica’s ice shelves help to control the flow of glacial ice as it drains into the ocean, meaning that the rate of global sea-level rise is subject to the structural integrity of these fragile, floating extensions of the ice sheet,” the researchers write.

“Until now, data limitations have made it difficult to monitor the growth and retreat cycles of ice shelves on a large scale, and the full impact of recent calving-front changes on ice-shelf buttressing has not been understood.”

The researchers combined data from multiple optical and radar satellite sensors and show that from 1997 to 2021, Antarctica experienced a net loss of 36,701 square kilometers (1.9%) of ice-shelf area that they say cannot be fully regained before the next series of major calving events.

“Mass loss associated with ice-front retreat has been approximately equal to mass change owing to ice-shelf thinning over the past quarter of a century, meaning that the total mass loss is nearly double that which could be measured by altimetry-based surveys alone,” they say, adding that further ice retreat could have a significant impact on sea level rise in the future.

Previously, studying satellite imagery of Antarctica has been challenging.

“You can imagine looking at a satellite image and trying to figure out the difference between a white iceberg, white ice shelf, white sea ice, and even a white cloud. That’s always been a difficult task,” JPL scientist Chad Greene, lead author of the study explains.

“But we now have enough data from multiple satellite sensors to see a clear picture of how Antarctica’s coastline has evolved in recent years.”

NASA says that scientists don’t think it is possible that Antarctica can regrow the ice that it has lost since prior to the year 2000 before the end of the century and that instead, it is more likely that they will experience “major” calving events in the next 10 to 20 years.

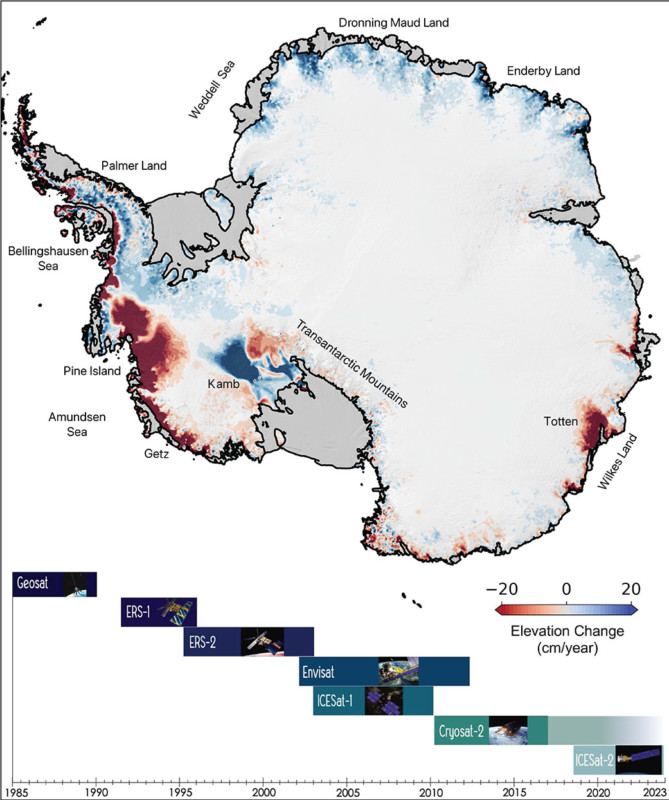

The second study, published in Earth System Science Data, goes a step further and shows how the thinning of Antarctic ice has spread from the continent’s outer edges towards its interior, almost doubling the western part of the ice sheet over the last 10 years.

“The largest uncertainty in future projections of sea level change comes from the uncertain response of the Antarctic Ice Sheet to the warming oceans and atmosphere,” the study, titled Elevation change of the Antarctic Ice Sheet: 1985 to 2020, finds.

The scientists combined almost three billion data points from seven satellite instruments to produce the longest continuous data set of the changing ice sheet, NASA reports.

“The ice sheet gains roughly 2000 km3 of ice from precipitation each year and loses a similar amount through solid ice discharge into the surrounding oceans. Numerous studies have shown that the ice sheet is currently out of long-term equilibrium, losing mass at an accelerated rate and increasing sea level rise.”

There is considerable uncertainty in the scientific community when it comes to forecasting how sea level rise as a result of changes to Antarctica’s ice sheet. It took years to analyze this new data — thousands of hours of time on NASA servers — which JPL’s Johan Nilsson, lead author of the study, says is worth it.

“Condensing the data into something more widely useful may bring us closer to the big breakthroughs we need to better understand our planet and to help prepare us for the future impacts of climate change,” he says.