Remembering Ansel Adams Through the Life of One Student

![]()

Ansel Adams was born on February 20, 1902, in San Francisco, California. An exceptional photographer and environmentalist, he is best known for his iconic black and white images of the American West.

Adams’s somewhat solitary childhood led him to find great joy in nature, often taking long walks in the wild reaches of the Golden Gate. He spent a significant amount of time in Yosemite and the Sierra Nevada each year from 1916 up until his death in 1984.

In 1919, he joined the Sierra Club, which proved to be quite vital to his early success as a photographer. His first fully visualized photograph, Monolith, the Face of Half Dome, taken in 1927 on a hike in Yosemite, was the image that would launch his great influence to come.

At one with the power of the American landscape, and renowned for the patient skill and timeless beauty of his work, photographer Ansel Adams has been a visionary in his efforts to preserve this country’s wild and scenic areas, both on film and on Earth. Drawn to the beauty of nature’s monuments, he is regarded by environmentalists as a monument himself, and by photographers as a national institution. It is through his foresight and fortitude that so much of America has been saved for future Americans. —President Jimmy Carter

Shortly thereafter, he began to pursue a “straight photography” style, meaning he attempted to depict scenes realistically and with great detail without manipulating the subject matter in the camera or in the darkroom. His photography group, Group f/64, brought this style of photography to national attention in the early 1930s.

An unremitting activist, Ansel Adams’ photographs became symbols of Wild America, evoking the emotional experience of the natural beauty embodied by the wilderness he captured on film. Some criticize him of photographing an idealized version of wilderness that no longer exists; however, many of the places he photographed are the very ones that are now preserved forever as a result of his efforts.

Ansel Adams’s Infrared Photography

Many people are familiar with the iconic work of Ansel Adams. His remarkable black and white landscapes and his conservation efforts have lived on long after him, but there is one facet of his photography that has gone widely unheard of in today’s world: his infrared work.

The modern digital age has made infrared photography more accessible and relatively easier than ever before. Only in the last few years has infrared started to become more popular in the creative sector; whereas, it was tremendously uncommon decades ago when Ansel was in his prime. In honor of his 120th birthday, we interviewed a former student of his to dive into this other side of him.

“Infrared wasn’t popular. Infrared was just a ‘gimmick’. Nobody understood it,” says Laurie Klein, an accomplished infrared photographer and former student of Ansel Adams. “Honestly, infrared was kind of like the bastard because it was so hard to do. You couldn’t do infrared back then unless you really dedicated yourself to it and you learned the technical part.”

As a biomedical student at Rochester Institute of Technology, Laurie learned about infrared. Struggling to grasp the intensive technical aspects of biomed, she was on the verge of failing the program. Luckily for her, she had a supportive mentor who took notice of her interest in infrared. He agreed to pass her so long as she went on to study with either Minor White or Ansel Adams.

Laurie had initially been under the impression that infrared was only used for diagnostic and research applications, but after some research of her own, she found that Ansel was shooting landscapes in infrared. Being interested in landscape photography herself, he was the one she ultimately chose to be her next mentor.

Yosemite in the summer of 1973 was the backdrop for young Laurie and her fellow classmates as they studied infrared with the great Ansel Adams at one of his workshops. Learning from her idol and seeing how he produced his work, she fell in love with the infrared landscape. She knew then that this was what she wanted to do, but she had no idea where this journey would eventually lead.

“It wasn’t just the infrared at the time, it was his passion, and it was how he was helping people be aware of what nature’s all about and that we shouldn’t be ruining it. And that spiritual magic he had in his photographs with the infrared–that’s what I wanted to do,” Laurie remembers.

Much like the natural monuments he photographed, Ansel Adams was larger than life. His generous, charismatic personality could light up a room, and this transferred to his teachings as well. He had the spirit of a good-humored child but was also known to be a perfectionist.

Ansel Adams was many things, but above all else, his most awe-inspiring trait was his immense passion for everything he did. His passion for the land was so exuberant that he even began to resemble it with age.

“We were sitting out in the middle of Yosemite, and he was doing a one-on-one with me. He had very arthritic fingers,” Laurie recalls. “I just remember him pointing around to different things with his fingers, and how his body looked like it was part of nature.”

“He was such a passionate human being in a technical sense and art sense and also about the land.”

The Technical Prowess of a Photography Master

A technical master, Ansel had his rules. Technology was a significant component of his work, and he was of the school of thought that you must learn the rules of photography before you can break them.

Ansel Adams had the ability to pre-visualize his images, both in black and white and in infrared. His iconic Monolith, the Face of Half Dome was initially shot with a yellow filter, but this did not produce the exact image he had envisioned. He then retook the photograph using, instead, a red filter in order to darken the sky and dramatize the towering rockface.

“This photograph represents my first conscious visualization; in my mind’s eye I saw (with reasonable completeness) the final image as made with the red filter…” Ansel stated. “The red filter did what I expected it to do.”

This visualization led to the development of the Zone System, his famous and highly complex method of metering for details in the shadows and details in the highlights. Nailing the proper exposure and retaining as much detail as possible was key to producing the exceptional images that he did, along with knowing how to translate his love and passion for the landscape and his art.

“The thing about his work was your jaw would drop because the different zones were all there, and it was just so lush,” Laurie says. “It was very riveting.”

His unrelenting fascination for the technical aspect of photography led Laurie to imagine how he would have felt about the different infrared and post-processing tools available to us now.

“I think he would’ve enjoyed it to no end,” Laurie says. “But I also think it would never be to the compromise of the technical piece.”

Being that Adams was a black and white photographer, it is unlikely he would have had an interest in the color infrared filters. His infrared work was shot primarily in 720nm, but Laurie believes he would have loved to have played with it all. Most importantly, though, he certainly would have insisted on learning all the rules of the new technology before going off to make it his own.

Perhaps music is the most expressive of the arts. However, as a photographer, I believe that creative photography when practiced in terms of its inherent qualities, may also reveal endless horizons of meaning. —Ansel Adams

During the ‘73 workshop, Ansel had his students walk around with empty slide cutouts to teach them about framing. The overwhelming beauty of nature, especially in Yosemite, can make it rather difficult to compose an effective image. This exercise helped Laurie understand the limitations and vast opportunities available with her camera.

“I learned from him that you crop in the camera, you don’t crop later on,” Laurie says. “People do that now, it’s like how do you do that when you’re out there in the field? When you get that hit, when you get an image, when you get the feeling…

“It’s a combination of the vision and the feeling. That’s where you know where to crop. Because later, you’re cropping in the darkroom or behind a computer and the feeling’s not there.”

Ansel often said that everything should be in your photo for one of two reasons: composition or content. According to him, if something didn’t fall under one of those two categories, then it didn’t belong in the photograph.

A Lifelong Journey in Photography

Beyond her time studying with him, Laurie found that different parts of her journey were constantly pointing back to Ansel Adams in small ways. After the workshop, Laurie took a photo history class from Beaumont Newhall, a famous photo historian and a friend of Ansel Adams. Unsure of what to do next, she spent some time out West. Eventually, she made her way back to the East Coast where she got a job teaching high school students.

“I realized that was another journey that inspired me with Ansel because he was so passionate about teaching and sharing and the Zone System and the technical piece,” she says.

She decided to go to graduate school to immerse herself more in landscape photography. She enrolled at Ohio University where she had the opportunity to teach undergraduates while she studied.

“I had two amazing teachers that were both nature photographers,” Laurie says. “One had studied with Minor White and knew Ansel, so again, it came back. It was a very small world. Much smaller than now. There always seemed to be a connection to Ansel, to Minor, to people that I just really admired.”

“It doesn’t matter what you end up doing, you have to have the passion. You also have to have the visual prowess. And he did.”

Following graduate school, she moved back to Connecticut and continued teaching.

“I taught at a college in Connecticut, and one of my students wanted to learn about hand coloring,” she says. “Berol, which is Prismacolor, lived in my hometown, and I talked to them and they wanted to sponsor me. Infrared is one of the best mediums for hand coloring because you hand color the highlights. And what’s infrared? It’s all highlights.”

In time, she opened a school and a gallery of her own. She exhibited Ansel Adams’ photographs in her gallery and taught the things she learned from him in her school.

In the wake of her divorce, it became difficult to run both a school and a gallery while also being a stay-at-home mom, so she started doing wedding photography. Laurie knew there was nothing unique about what she was doing. She didn’t want to just capture moments at a wedding anymore; she wanted to make art. That was when she began creating infrared hand-colored images for her clients.

“The work became the wall art for most people,” she says. “I was in magazines; I’m on covers of books. It was all based around what [Ansel] taught me.”

If Ansel Adams’ work teaches us anything as photographers, it’s just how important it is to understand the technical side of the craft. There have to be details in the shadows and details in the highlights, even in digital. If a photograph doesn’t have these details, your eye can’t stay in these spots.

“His stuff was so lush where there are so many nuances,” Laurie says. “The mid-tones, the blacks…it’s like, ‘Oh my god, how do you get that? How do you see that in a color scene?’ He could pre-visualize color into black and white and into infrared. Absolutely infrared. And I think, too, that’s why he was so good with infrared because he had the technical piece down. Because infrared is a lot about the technical.”

A Living Tribute to Ansel Adams

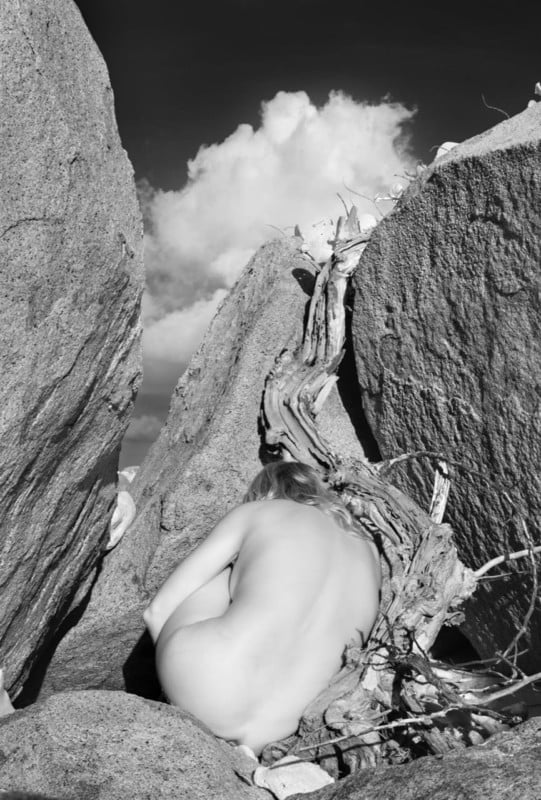

While Ansel Adams did not shoot much in the way of portraiture, Laurie Klein has become known for photographing the female form in the landscape. She shared Ansel’s passion for the landscape and learned from him how to find the scene. From there, she taught herself where to place the people within the scene and to find the relationship between the people and the landscape.

“The reason my work is different than most people’s in that kind of genre is because the landscape was the most important thing and then I knew where to put the people,” she says. “So it wasn’t about the people and then I put the landscape around them. And that was totally because of him. And I’m still doing it. I’m still teaching it, and I keep talking about him every way I can because I think for us to have a mentor, even if he’s a mentor from a distance…

“The thing about him is that he has good composition and he had a passion. A lot of people don’t and they’re learning from people that don’t, and that’s not good.”

Ansel Adams is arguably the most influential photographer this world has ever seen. His work is responsible for the preservation of many of the most beautiful wilderness areas in America.

Apart from his more famous pieces, however, much of his other work has gone unseen by the majority of the public. Very little is known about his infrared work, even in this digital age where virtually everything can be found on the internet. Because infrared photography was such a niche genre, Ansel’s use of infrared was mostly kept within that community.

It seems that this information has largely been lost to the ages; even the institutions most knowledgeable on all things Ansel Adams are unfamiliar with his infrared work. We can only hope that the insurgence of infrared photography in recent years will lead to the uncovering of more information in this area of his life.

About the author: Alexis Hartman is a manager and writer. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.