Researchers Use Smartphone Camera to Identify Acne-Causing Bacteria

![]()

Researchers from the University of Washington have developed a way to use smartphone photos to identify potentially harmful bacteria on skin and in the mouth. The method can visually identify microbes on the skin that contribute to acne as well as those that cause gingivitis and dental plaques.

The team was led by Ruikang Wang, a University of Washington professor of bioengineering and ophthalmology. The group of researchers combined a smartphone case modification with a set of image processing methods to show bacterial on images taken by a standard, conventional smartphone camera. The result is what the researchers say is a relatively low-cost and fast method that could be used at-home to assess the presence of harmful bacteria.

“Bacteria on skin and in our mouths can have wide impacts on our health — from causing tooth to decay to slowing down wound healing,” Wang says. “Since smartphones are so widely used, we wanted to develop a cost-effective, easy tool that people could use to learn about bacteria on skin and in the oral cavity.”

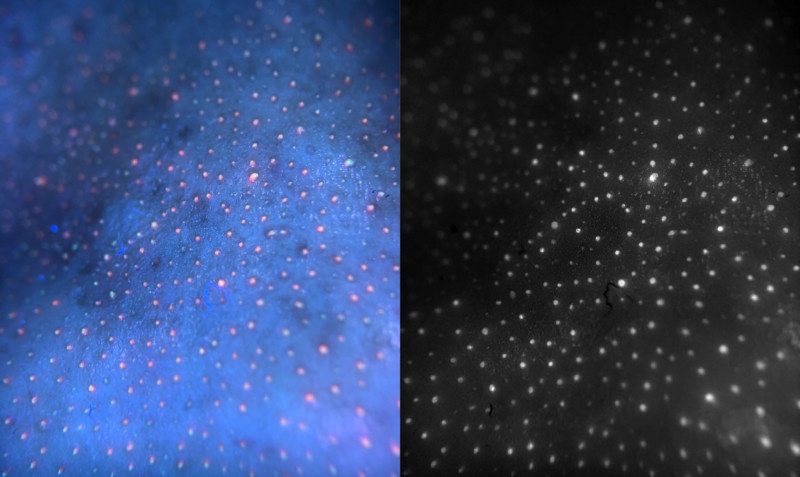

Wang explains that bacteria are not normally easy to see using conventional smartphone photos because they capture in RGB. In short, the images that are captured are from different wavelengths of light in the visual spectrum, but many bacteria emit colors that are beyond that spectrum and hence are invisible to it.

To get around this problem, the researchers augmented a smartphone camera with a 3D-printed ring with 10 LED black lights arranged around it.

“The LED lights ‘excite’ a class of bacteria-derived molecules called porphyrins, causing them to emit a red fluorescent signal that the smartphone camera can then pick up,” lead author Qinghua He, a UW doctoral student in bioengineering, says.

Many bacteria produce porphyrins as a byproduct of their growth and metabolism. Porphyrins can accumulate on the skin and in the mouth where the bacteria are present in high numbers, according to co-author Yuandong Li, a UW postdoctoral researcher in bioengineering. The more porphyrins that are seen on the surface of the skin, the greater chance there is of acne to form.

According to a summary from the University of Washington, the LED illumination gave the team enough visual information to computationally convert the RGB colors from the smartphone-derived images into other wavelengths in the visual spectrum. This generates a “pseudo-multispectral” image that consists of 15 different sections of the visual spectrum — rather than the three in the original RGB image.

The team says that trying to obtain that kind of visual information up front would have required large and expensive lights, which makes the use of inexpensive LED blacklights considerably more approachable for widespread adoption. Theoretically, the image-analysis pipeline could be modified to detect other bacterial signatures that illuminate under LEDs.

“That is the beauty of this technique: We can look at different components simultaneously,” said Wang. “If you have bacteria producing a different byproduct that you want to detect, you can use the same image to look for it — something you can’t do today with conventional imaging systems.”

Wang says that there are multiple directions the team can go in from here as they explore the complex environments of the human body and search for more ways to address different problems that can occur there. the full research paper can be accessed here.