MoMA Wants Your Photos for Free, Perpetually, and ‘Any Purpose’

![]()

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is soliciting photographers to share photos on Instagram based on monthly themes. Those who participate will be featured on the MoMA’s social channels, but also give the museum significant rights to use the photos “for any purpose.”

In honor of National Photography Month and its new exhibition Fotoclubismo: Brazilian Modernist Photography, 1946–1964, the museum is encouraging photographers to “get creative with a new photo challenge.” It is based on the Fotoclubismo idea and on the achievements of São Paulo’s Foto-Cine Clube Bandeirante (FCCB), which the musuem describes as “a group of amateur photographers whose ambitious and innovative works embodied the abundant originality of postwar Brazilian culture.”

Called the MoMA Photo Club, the museum states that each month starting in May — for an undisclosed period — it will offer a new theme and host, kicking off with mountain climber and environmental activist Conrad Anker with the theme “Abstractions from Nature.”

The museum is calling on anyone to share their “abstractions from nature” by taking “a closer look at the world around you” and capture it from a new perspective. In return for submissions, the MoMA says that it will use those photos on its social channels, the MoMA website, and on digital screens in New York City subways.

We can’t wait to see what you make. Share your photos with us using #MoMAPhotoClub. Select photos will be featured on our social channels, the MoMA website, and on digital screens in select New York City subways.

But the fine print on MoMA’s website explains that those who use the hashtag would be giving up significantly more of their image rights. This would not immediately be noticed by those who only saw MoMA’s Instagram post above or did not read the lightly-colored fine print on the announcement page which is not easily navigable to from Instagram.

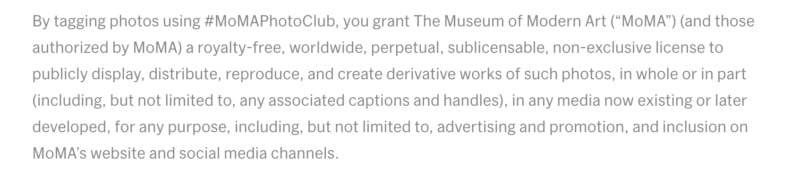

By tagging photos using #MoMAPhotoClub, you grant The Museum of Modern Art (“MoMA”) (and those authorized by MoMA) a royalty-free, worldwide, perpetual, sublicensable, non-exclusive license to publicly display, distribute, reproduce, and create derivative works of such photos, in whole or in part (including, but not limited to, any associated captions and handles), in any media now existing or later developed, for any purpose, including, but not limited to, advertising and promotion, and inclusion on MoMA’s website and social media channels.

Not only can photos be used in the way that MoMA describes on Instagram posts advertising the event, but the museum states that using the hashtag gives them implicit right to use that photo in perpetuity, sublicense it, and use it “for any purpose” including commercially which includes advertising and promotion.

“It’s certainly an overreach and a rights grab,” Mickey H. Osterreicher, the General Counsel for the National Press Photographer’s Association tells PetaPixel. “It’s unfortunate that once again that far too many people devalue photography. What is wonderful, obviously, is that certainly because everyone has a cell phone and therefore everyone has a camera, everyone can take pictures, but that doesn’t make everyone a photographer — but that also doesn’t mean that their images don’t have value.”

Osterreicher says that it is particularly disheartening to see that this claim of rights was made by a museum, an organization that is supposed to recognize creative work and artists.

“You’ve got a museum that’s supposed to value creative work, whether it’s by an artist with a paintbrush or a sculptor with a chisel, or a photographer with a pro camera or even just an iPhone,” he says. “We all recognize some incredible images that are made hundreds if not thousands of times a day by people using their iPhones and it’s very creative work and it certainly has value. To make it seem very open and friendly while in the meantime the fine print says that you’re granting all these rights not only for them to use them, but to use them into perpetuity to be able to sublicense them and to be able to use them for advertising and promotion is very disappointing.”

Osterreicher says that he doesn’t think it’s likely that the MoMA would ask painters to send in their paintings, so why it believes that asking the same of photographers is fine hurts the medium greatly. He references the case where Andy Warhol took and used a photographer’s photo as the basis for his work, and how Warhol seemed to believe that he was doing the photographer a favor by using her work beyond the scope of the license. Osterreicher describes it as a kind of artistic “elitism” that MoMA’s alleged overreach here is another symptom of.

“Clearly if there wasn’t value to these images, why would they be asking for them and these rights?” he poses.

The MoMA did not immediately reply to a request for comment.

Osterreicher encourages all photographers, regardless of camera or medium, to always review the fine print from any organization where photos are solicited to assure that the value of photography is upheld.

Image credits: Background of header photo licensed via Depositphotos.