What If The ‘Collapse’ of the Camera Industry Was Based on Flawed Data?

Doom-and-gloom stories of the state of the camera market have been pretty common over the past year due to COVID-19. But what if the data used to determine the health of the industry was flawed?

Before we can get into why this might be the case, we have to first look at the information that is currently available for analysis. In the video above and in a story published here, Lensvid looks at CIPA camera sales data that many outlets, including PetaPixel, use as one of the metrics to gauge the strength of the photography industry. This has been the standard. From that data, Lensvid’s editor Iddo Genuth explains in detail some of the major important points that the industry went through since 2010.

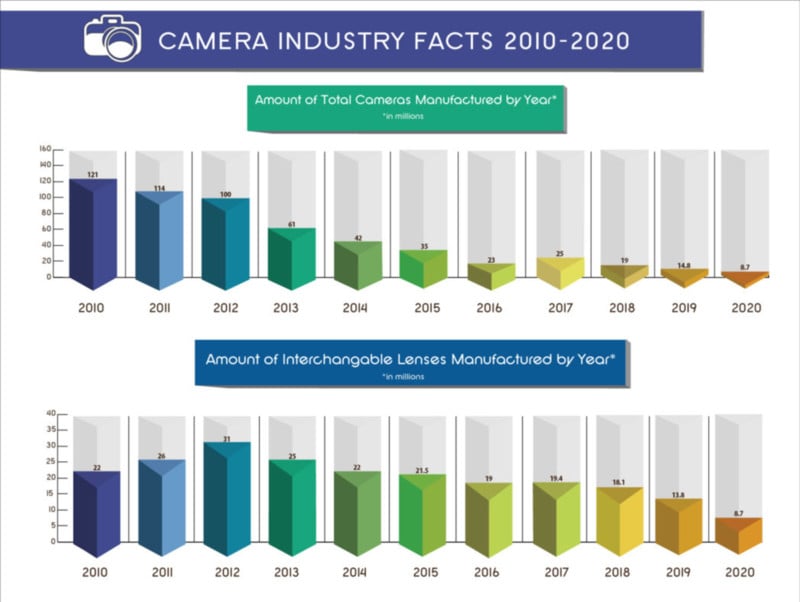

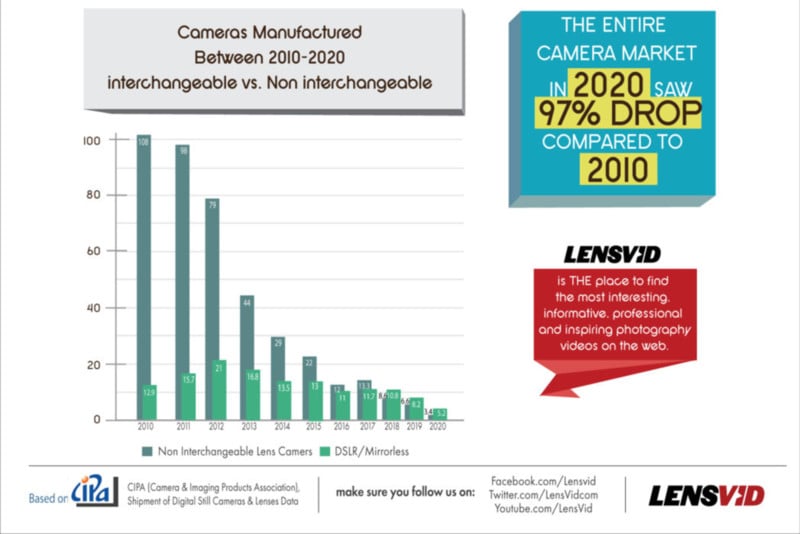

The year 2010 is important because it is the last year that standalone cameras were shown to outpace previous years’ sales as well as one of the last years that camera sales were anywhere close to smartphone sales. Note this, as the fact that cameras and smartphones are not seen as sharing a market is important. In 2010, digital camera sales moved more than 121 million units. Two years later, interchangeable lens cameras (DSLRs and mirrorless) hit their all-time high of 21 million units (over 16 million of which were DSLRs).

This is important also, as it shows how small the interchangeable lens market is compared to the entire camera market as a whole. This will have ramifications going forward.

Genuth says that based on this data, the fall of the industry started sometime between 2010 and 2012, right as both the entire camera market and specifically the interchangeable lens markets both peaked. From there, the following years show monumentally steep, compounding falloff.

“The fall of the camera industry started somewhere between 2010 and 2012 and really became visible in 2013 when the number of cameras sold dropped to only 61 million units, basically halving the entire industry,” Genuth writes. “Another three years forward and we see an even bigger drop by more than half in 2016.”

Genuth says that much of this falloff can be attributed to the increased adoption of smartphones that include cameras that were able to achieve results that the average consumer felt were “good enough” to leave their standalone cameras at home.

While the standalone fixed-lens camera market collapsed, so did sales of interchangeable lens cameras.

“The global market for interchangeable lens cameras dropped from 21 million in 2012 to only 13 million in 2015 and again to 8.2 million in 2019,” he continues. “This is more than a 60% decline in sales in 7 years for a market segment that was not that big, to begin with.”

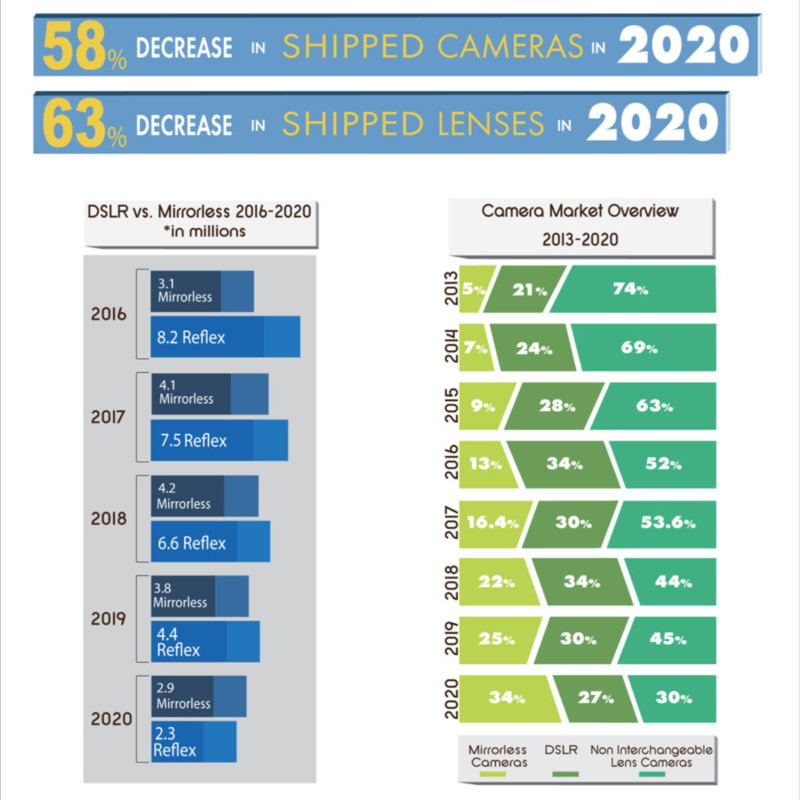

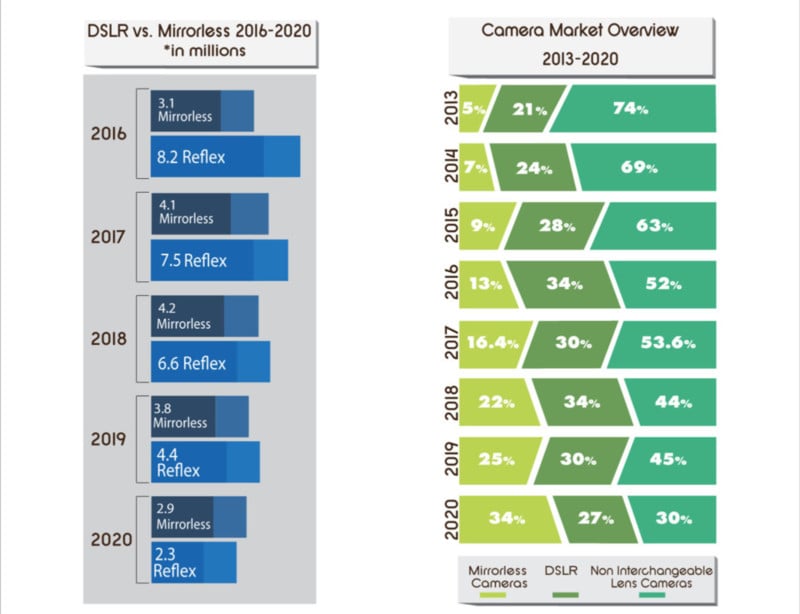

In 2020, the camera market came to an absolute halt around March when the market seemed to bottom out. As reported earlier this month, 2020 was a rough year.

“Both in interchangeable lens cameras and in lenses we see over a 36% decrease in sales in a single year, the biggest drop in these two categories for a long time. Compact cameras dropped by almost half (48% to be precise), but that number is not really surprising anymore,” Genuth writes.

Even with work from home orders, the need for reliable webcams did not seem to prop the industry much, if at all. This despite the fact many if not all of the major manufactures released software that would turn cameras into webcams seamlessly.

Based on this data, the future for camera manufacture, according to Genuth and Lensvid, is not a bright one.

“Even in a very optimistic scenario where the pandemic will be mostly behind us by the end of the year, we can’t see a significant recovery of the market, certainly not to the levels of the 2019 market (which as we have seen were already quite low),” he writes.

“What does this mean for the industry? well, prices will continue to stay high, manufacturers will have less money to spend on R&D, and companies struggling to survive even before the pandemic might not survive or have to sell, just like Olympus did with its Imaging business which is now part of JIP,” he says.

You can read the full detailed Lensvid breakdown of the photography industry’s trends here.

While no one can predict the future, Genuth makes some good points that are based on market trends in the making for the last decade but as mentioned, it’s all based on CIPA data.

But what if that CIPA data was an incomplete, poor picture of reality?

Take, for example, CIPA battery life numbers for new cameras: that data has been suspect for some time. Privately, camera companies have told reviewers and journalists that the published CIPA battery specifications for new cameras should not be taken at face value and that the organization’s testing methods haven’t adapted well from DSLRs to mirrorless. This goes to show that CIPA is not infallible and is prone to adjusting too slowly to changes in technology. In that same thread, what if CIPA’s shipment data for cameras was incomplete due to how it recognizes what a camera is?

Things wouldn’t look so bleak if CIPA counted smartphones as cameras; it would look quite the opposite, actually. Even though consumers treat smartphones as “every day” cameras and they have all but fully replaced compact fixed-lens cameras, CIPA doesn’t see them as such. As a result, looking only at this data will continue to paint a bleak picture of how photography as an industry is going despite the fact that more photos are being taken now than ever before.

In reality, the future of photography’s growth and expansion lies in mobile and the longer this is denied or ignored, the longer the photography industry will appear to be in an uncontrollable tailspin.

(Lenstip article via The Online Photographer)