Shooting Daguerreotypes of California Redwoods

![]()

This trip has been waiting in the wings ever since I made my first successful daguerreotype in the redwoods two years ago. I actually planned on going as early as August this year, but one project after another kept getting in the way, and for months I kept pushing it back by a couple of weeks.

23 years ago I traveled up to this same spot in Arcata, California, for the first time. It was the first stop of what would become a life-changing adventure. This was less than three years after I arrived in the US as a refugee, and at the time I was working nights in fast food places while attending community college full-time and getting ready to try and transfer to UCSD as a biochemistry major.

Being amid those woods for the first few days of the trip made me realize that my life must be dedicated to my first love of photography, and subsequent travel up and down the west coast set that in stone.

Upon returning, I switched my major to photography and started the long and winding road of working in various photo businesses in order to appreciate and learn all various aspects of this noble art. So this forest always held a special place in my heart.

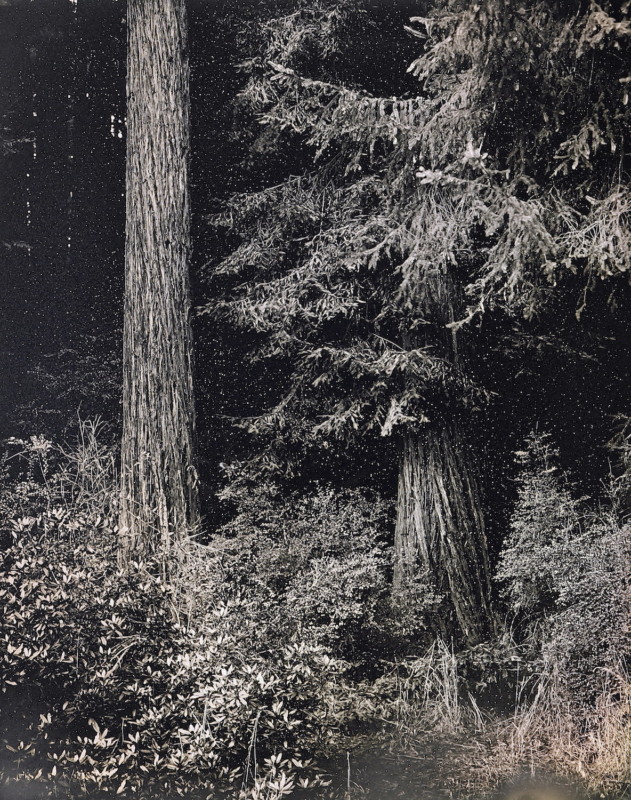

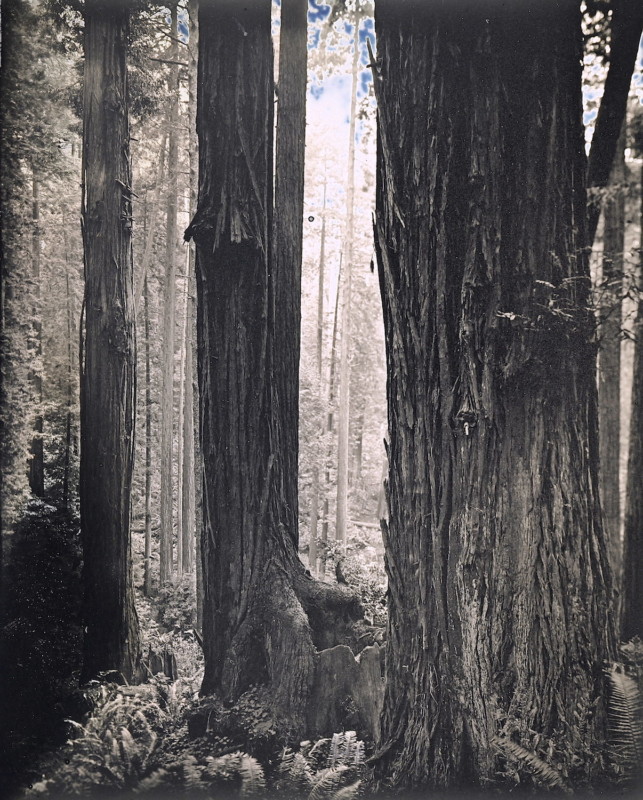

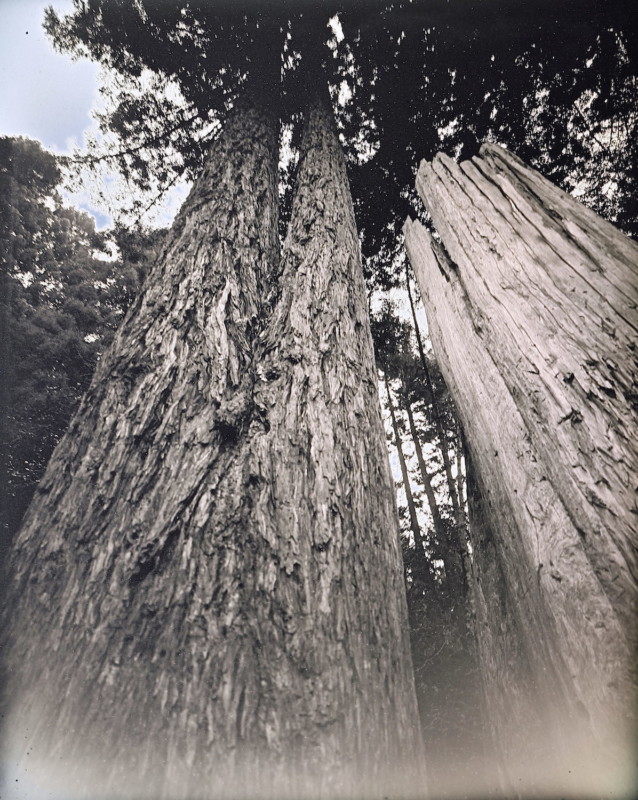

Redwood trees are incredible. They are the tallest trees on Earth, some reaching well over 300ft, and they can live past 3,000 years, with trunks that are over 20ft in diameter. Their bark is dark red, and their enormous branches, located only at the top part of the tree, block out almost all sunlight with dense needles.

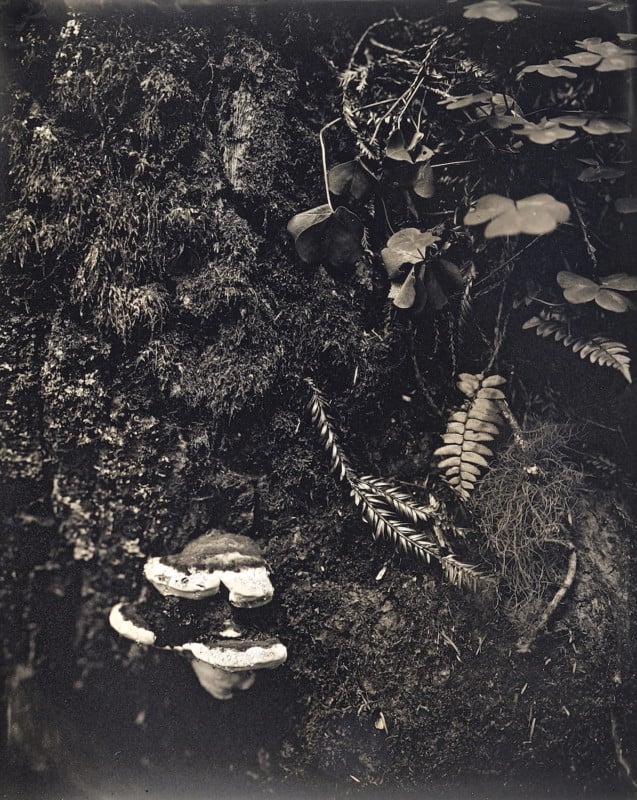

In the summer, when it’s 95°F in the town square less than a mile from the forest, as soon as you walk into the woods you want to put on a sweater. It’s almost always damp in there as well, as redwoods actually get a lot of moisture by trapping coastal fog in the morning, condensing it on needles, and raining it down. Being among trees that size and of that age really puts things in perspective.

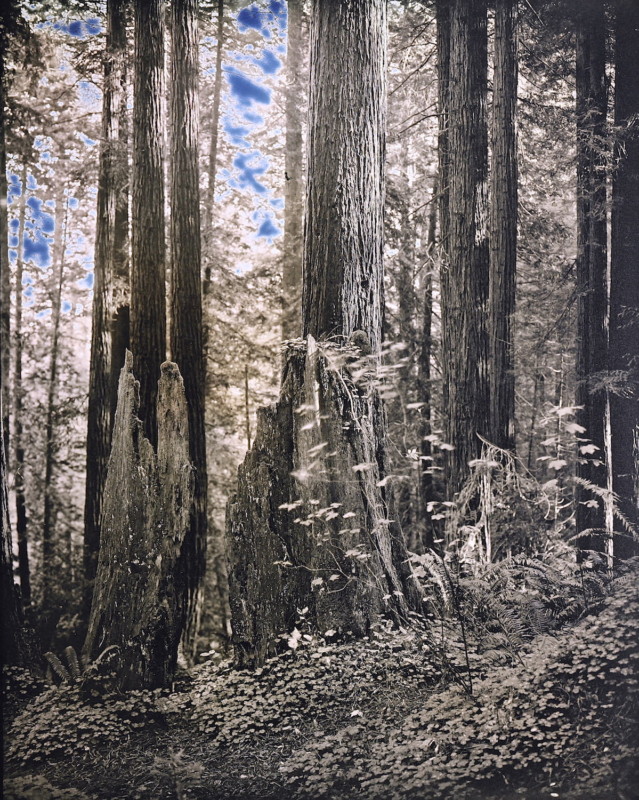

Another thing that makes one realize the ravages of history are the countless enormous burned-out stumps that dot the forest as far as the eye can see. Those were the real old-timers, the original old growth.

Natives never cut those trees, and while considering them sacred, never actually lived within the forest, always in nearby meadows or river valleys. When European settlers arrived, especially starting with the 1849 California Gold Rush, there was suddenly a great need for building materials. Imagine the expressions on the faces of loggers when they saw that there was a forest that ran for hundreds of miles, with trees so big that you could build 40 5-room homes from one single tree!

Nature is still only rarely a first concern when people do things, and back then it was much less so. Humans went cutting, and, by the time things slowed down, literally less than 2% of that original forest was left. At that point, people saw a vast land in front of them, full of giant stumps which no man or machine at that time could uproot. People wanted that land for agriculture and to graze their cattle on, so they really wanted those stumps gone.

At some point, some mildly bright individual came up with the idea of burning the stumps. Problem is, redwoods evolved to withstand fires pretty well; their bark is fibrous and snuffs out the flame by starving it of oxygen, so only extreme and prolonged heat can get through that bark and down to actual wood. I guess the proposed solution was to try and burn them with root fires, so they would burn from the inside.

The spectacle must have been harrowing, and I can’t imagine how long or fierce those fires raged, but when it was all over, the outer portions of all those stumps still proudly stood; charred tubes 10-20ft tall, many of them wide enough to pitch a tent inside and have a fire next to it.

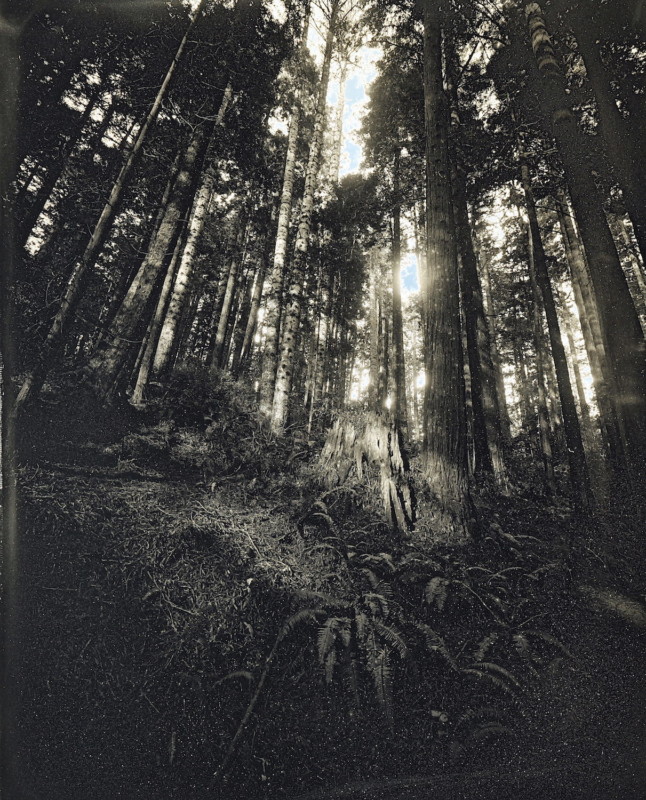

These ghostly grim reminders of human greed and avarice were also not dead. You see, when one dies naturally, redwoods sprout new shoots from their roots, as nearby original trunk as possible, so a new forest soon sprung up in the land that people could not tame, and you can see in a few of my plates that old stumps usually have 2-3 new shoots right at their bases.

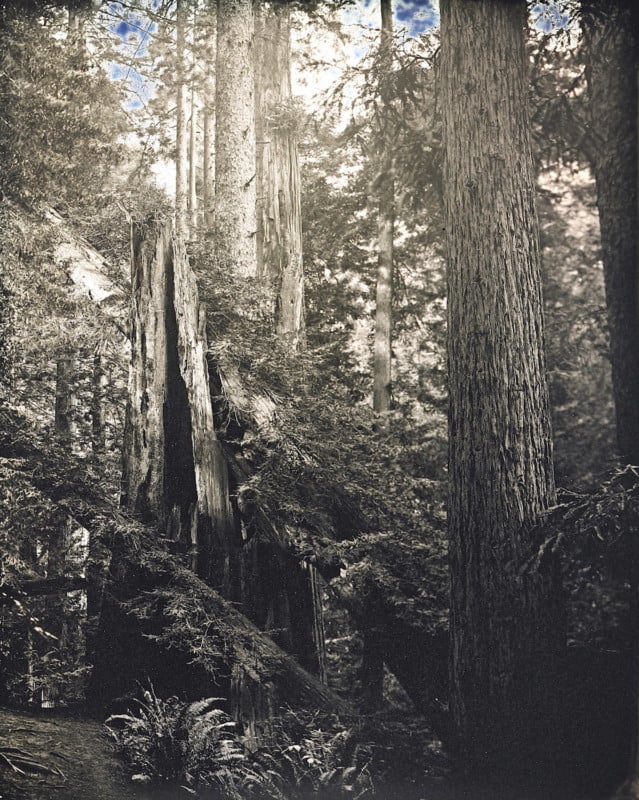

One of the plates also captures a peculiar and beautiful natural phenomenon I was not expecting to see. Around 2005 or 2006, there was an abnormal for the area weather event, with something akin to a miniature tornado forming, and that whipped through the forest pretty strongly. Redwoods don’t usually fall from wind, but indeed their root systems are actually very shallow, so if a strong wind is combined with rain, and the ground is soaked, they can topple over.

Shortly after hearing the news of that storm, I went back there to see the damage for myself. It was surreal, with devastation visible in every direction. After coming there many times, and being familiar with almost every turn in that lower part of the park, the place looked unrecognizable and totally surreal. It was like some sort of a lumberyard owned by careless giants, with splintered pieces the size of a train car jutting up in every direction.

Those who wandered in and wanted to go where they always walked freely to had to climb over and under and around huge trunks and crawl between branches. It looked like an absolutely impossible cleanup job, but I must say the city did an incredible job, and now it’s hard to tell which logs fell during that storm and which have been there for a century.

A particular scene though struck me as truly symbolic of the resilience of this forest. One of the largest and tallest of the old burned stumps was crushed and broken by three near-buy younger saplings during that storm, so that was the second time that tree was in danger of meeting its demise. But no, nature finds a way.

Not all of the roots of the younger trees must have gotten separated from the ground, and so when they all of a sudden found themselves in a 45° position, they reorganized their plan for growth and started sprouting branches all along the top portion of their trunks. This phenomenon actually gave rise to a form of bonsai called ‘raft style’, and I can’t wait to see what it looks like in 20-30 years.

Let’s get back to daguerreotypes though, redwoods do tend to get me rambling. Two years ago, I actually made one of my best plates to date at this same place, but I was not satisfied that it was the only one I secured that time. I felt that this time, especially after the grueling desert adventure, I was ready.

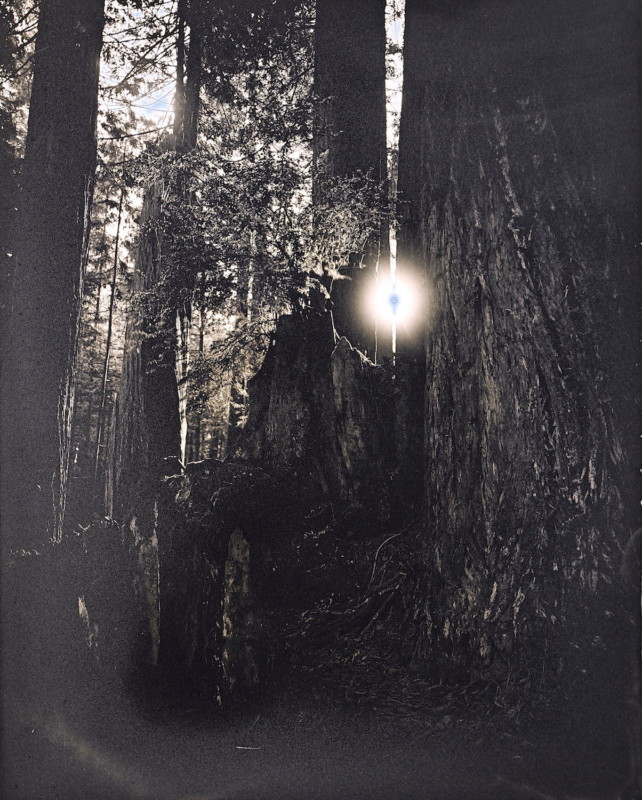

I’ll say that going from the ultra-bright Arizona desert to redwood forest lighting was extremely challenging, especially seeing how little UV is present that far north and this late in the year. Humidity was also the exact opposite of the desert, with dew point hitting early, suddenly, and hard, so a couple of my plates suffered from that, but I think in one with the sun peeking through the old burned-out log it really worked out splendidly.

I brought two cameras with me, knowing that my exposures were going to be long. One was my usual Zone VI, with 90, 150, 210, and 400mm lenses, and the other was a fixed lens Burke & James 4×5 Orbitar, with its 65mm Schneider. Sometimes I would set them both for similar exposures, or I would give the Orbitar such a long exposure that I could finish two plates with a faster lens on Zone VI.

The contrast in that forest is enormous, with deep shadows even midday registering at EV3, and splotchy sunlight getting through the branches unscathed being about EV13 or more. I’ve posted a phone photo for comparison. You can see the camera mid-exposure at the bottom of the frame, and I adjusted all values while still there to match the scene as closely as possible to what it appeared as to the naked eye.

I can’t really describe how happy I am with these plates, which are all 4x5in, by the way. Even the unexpected light leak or two along the bottom edge of some plates somehow doesn’t bother me at the least, when usually I’d be pretty upset about it. A few of these plates though set my personal best record for now, and outperforming them is what I will work tirelessly at, but I really don’t know how much better they can possibly get.

No digital reproduction on screen or in print can ever come near the beauty and depth of these unique plates. For example, one of the plates above appears a little warmer on the left than on the right. That’s actually opalescence of that plate playing tricks on the camera sensor — depending on the angle of view and lighting in real life, that plate changes hue from purple, to neutral, to golden, so holding it is not something I can ever hope to convey via this modern marvel of communication method.

I do however welcome anyone to contact me and make an appointment for a private viewing should you ever find yourself in San Diego.

All these plates at this point are available for purchase — feel free to contact me here.

About the author: Anton Orlov is an analog photographer and the man behind The Photo Palace, a 35-foot school bus that has been converted into a darkroom and presentation area for educational and artistic purposes. He previously created a transparent camera and the world’s smallest tintypes. Visit his website for more of his work and writing. This article was also published here.