Astronomers Warn Starlink Satellites Could Have a ‘Fatal’ Impact on Astrophotography

![]()

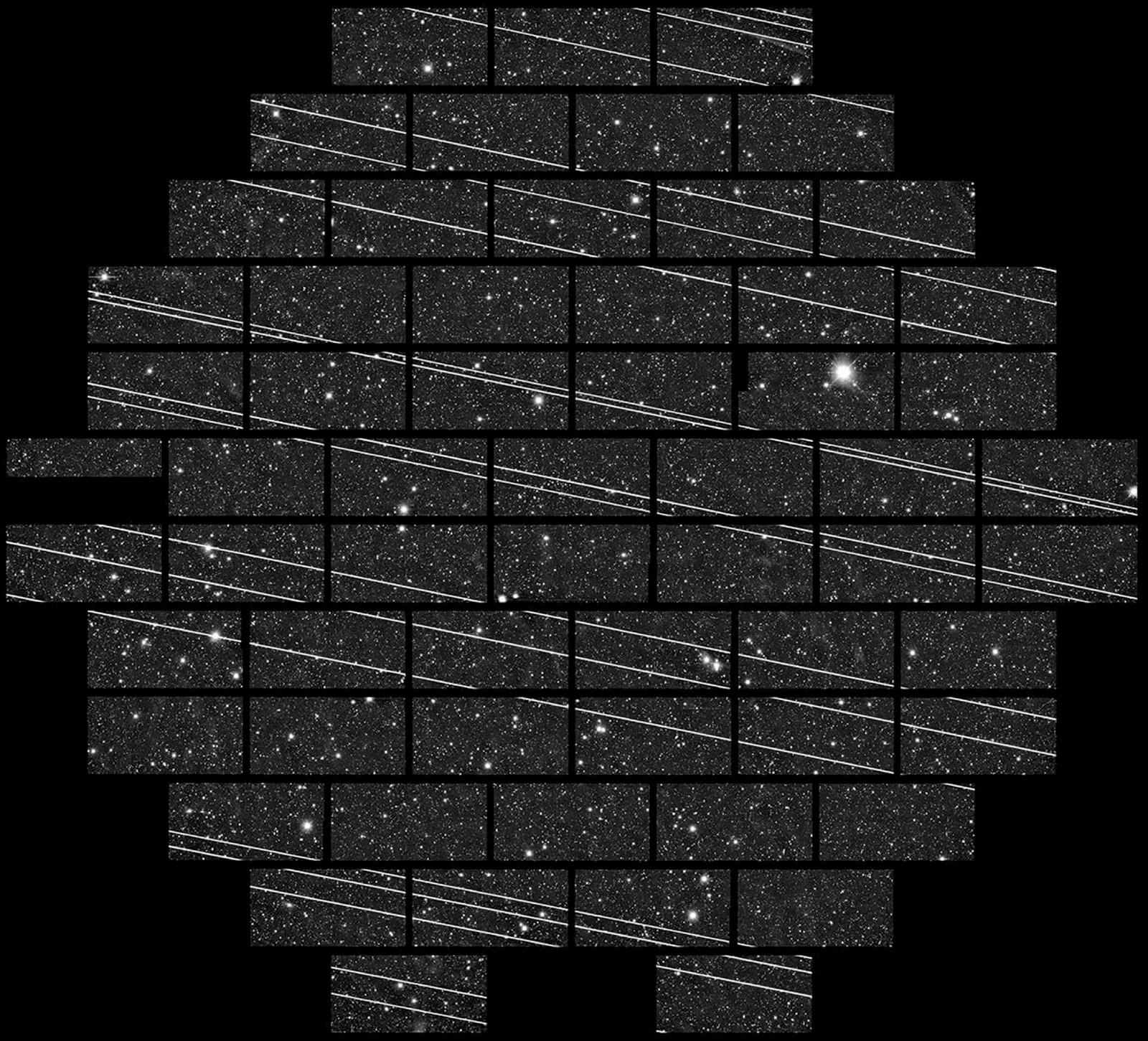

Hundreds of astronomers, satellite operators, and dark-sky advocates recently joined forces to call out a problem that impacts all three groups: the growing number of SpaceX ‘Starlink‘ satellites in orbit, and how these ‘constellations’ could actively hurt scientific progress and have a ‘fatal’ impact on some forms of astrophotography.

But this week’s report from the Satellite Constellations 1 (SATCON1) workshop offers a more comprehensive description of the issue at hand, why it’s a problem, how it’s a problem, and what regulators and satellite manufacturers can do to help.

![]()

The full report runs to 108 pages, including a great deal of technical detail on the challenges inherent in trying to either avoid or automatically remove the light trails caused by these satellite constellations, as well as the scale of the problem. For some the impact is described as “negligible,” for others it’s “fatal.”

And while most of the report concerns itself with the impact on scientific observations, they do address photography… and the news isn’t great. According to the report, the impact on “narrow-field” astrophotography using telescopes and telephoto lenses is rated as “significant but (potentially) tolerable,” but for wide-angle shooters the impact is worse:

A significant fraction of night photography is now done with wide-angle lenses that capture wide swaths of the sky. Also, most images are also created with relatively long shutter speeds ranging from 15-30 seconds for static cameras to many minutes on tracking mounts.

[…]

Given an average of two satellite trails per square degree per 60-second exposures near the horizon, as indicated by simulations, we do not see how wide-field astrophotography can be performed to current standards with the projected density and brightness of the steady-state configurations of the Starlink2 and OneWeb constellations. We rate this impact as fatal.

In the end, the astronomers offer nine potential solutions to the low-Earth orbit satellite (LEOsat) problem:

- Fewer satellites

- Fainter satellites

- Lower-altitude satellites

- Smaller satellites

- Satellites that are visible in a smaller fraction of the nighttime

- High-precision satellite attitude information

- Improved scheduling capabilities for observatories

- Improved image processing capabilities

- Novel sensors for the future

Some of these are less practical than others, and a proper solution will probably involve a mixture of several. Whatever we do, the astronomers want to make this clear that this is an important issue, and one that needs to be addressed if we don’t want to significantly hamper scientific discovery using ground-based telescopes… as well as astrophotography.

Sure, that last one is a bit of an “add-on” problem, but for the readers of this site, we’d sure like it taken into consideration.

(via DPReview)

Image credits: Header photo by Paxton Tomko, CC0