How I Shoot Pro Portraits with DIY Barn Doors

![]()

Recently, I had a portrait shoot with the legendary poet, rapper, and actor Saul Williams. It began with a simple stroke of luck: I saw he was scheduled to perform at a local club near my house, and so I did a quick search for the name of his manager. I easily found it and e-mailed them, introducing myself and explained that I would like to take his portrait.

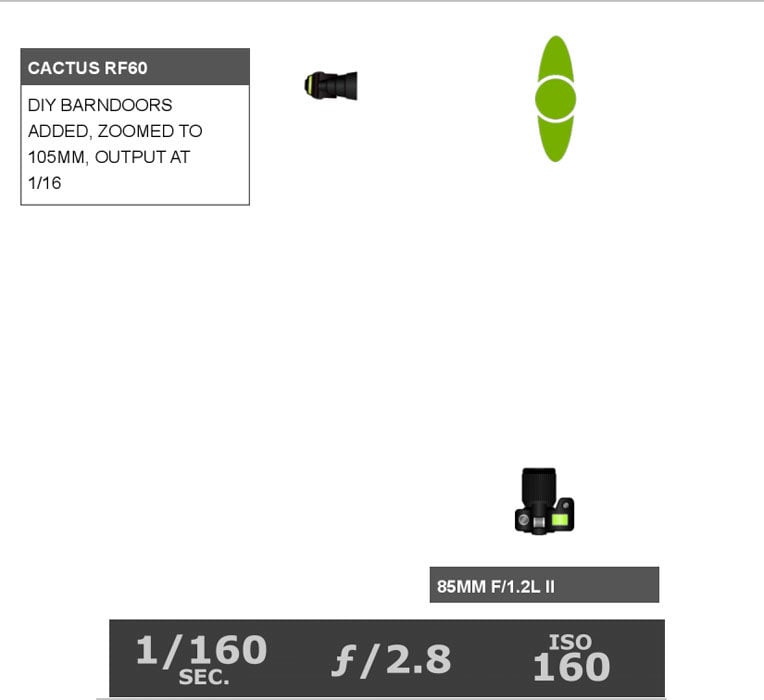

While revisiting his music, I had the thought that his voice, what he has to say, is a light in the darkness. This led me to the concept of putting Saul in a red scene, almost complete shadow, with a thin ray of pure white light illuminating his eyes. I didn’t just want a spot of light on him, but instead I wanted a thin line of light that ran across the wall and led through the frame to his face. This would require a light modifier that I didn’t own at the time; I would need barn doors for my flash.

Barn doors are metal flaps that can open and close, covering the left, right, top, and bottom of the light. They are typically used on studio strobes or hot lights. It’s the tool you need when you want to create a narrow line of light, either vertical or horizontal. The problem is that they aren’t available for small flashes. At least, they weren’t at the local camera shop I went to hours before my shoot was scheduled to begin (I had finalized the concept for the shoot that morning).

Coming up short at the camera shop, I decided to craft my own barn doors.

I grabbed a sheet of black foam board, some black gaff tape and a utility knife. I measured the width and height of the end of my flash and cut pieces of foam board to match it. After taping the four pieces together to make a tight-fitting box for the flash, I cut two additional strips of foam board and taped them over the opening. These flaps were the barn doors.

The gaff tape over the seams allowed them to hang open at a rough 45-degree angle. If I wanted an extremely small opening, I could pinch the flaps closed to the desired opening and then hold them in positioning with a strip of tape.

As you can see in the photo above, the DIY barn doors worked like a charm. The best part about the modifier is that you can smash it flat in your camera bag, once it’s removed from the flash because there is an opening on the front and back of it. It’s the smallest, cheapest, and most effective light modifier that I own.

A week later I was in New York City on a shoot and was staying in a hostel in Williamsburg. I had an extra day to do some test shooting, so I reached out to a few models. Two of the three models said that it’d be easier for them to come to me. I explained that I was staying in a hostel and sharing a room with two roommates, so space would be extremely tight. They were fine with that.

I knew that with the especially cramped room and limited wall space, I’d really need to get creative with my lighting. Enter my newly crafted barn doors. As you can see, I literally had to prop my light on a coat hanger and place my model by the door in order to have a blank wall space behind her.

With the flash’s close proximity to the wall and the addition of the barn doors, a cool, unplanned thing happened — lasers.

As I mentioned earlier, the Cactus flashes make a cool, prism-like effect when fired along a surface. When I place the barn door modifier on the flash and fire it along a surface, the prism effect is even more pronounced, becoming laser-like in appearance. I wanted the wall behind the model to be a little out of focus, allowing some separation between the model, so I shot at a slightly wider aperture of f/2.8.

In Lightroom, aside from my normal color grading, I also wanted to add a bit of graininess to the image to give the images a film noir vibe. This can be done in the Effects panel.

![]()

Experiment with the Amount, Size, and Roughness settings for the grain to find what you prefer. If you plan on any retouching to the image, do it before adding grain or the retoucher will hate you.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In the final shot, the tiny hostel room is no more. It’s just Larissa, alone in the void.

When I was photographing the Los Angeles industrial two-piece, Youth Code, I wanted to use this lighting effect. However, because the light is so narrow when lit from the side, it wouldn’t work to light both musicians evenly. Instead, I used two strobes, each outfitted with barn doors.

The barn doors were open a bit more this time, allowing the light stream to be a bit wider.

You can still use the barn doors to create a narrow, linear lighting effect when photographing a group of people. When I photographed the metal band Deafheaven, I wanted to have them isolated against a seamless white, with their bodies silhouetted and only their faces illuminated. I met them at the venue at the time of their sound check and I set up a white seamless sweep.

I would’ve preferred to just use a white wall as a backdrop, but this club, like most clubs, didn’t have open, white walls. Thankfully, I brought a portable backdrop kit and a roll of white seamless with me just in case.

After setting up the sweep, I placed two flashes on the ground about 5 to 7 feet in front of it, at either end. I aimed them up at a 45-degree angle to get an even spread of light across the white. I laid down a strip of black gaff tape just in front of the background lights, indicating where the band would stand. I placed my main light, with DIY barn doors attached, about 15 feet in front of the tape line and raised it up to 15 feet.

I needed the greater distance to allow the strip of light to be wide enough to cover all five band members. Had it been closer, the guys at each end of the group would’ve been in shadow. By raising the light to a high angle, the light falling on them was making more dramatic light than it would’ve at a straight-on angle. In the final shot, you can’t even see the background lights because they were behind the legs of the subjects—another bonus of using small flashes.

In the photo below, you can see that I am using a homemade snoot that is especially long—two feet long, in fact. I also placed a cookie (an object that is placed in front of a light source in order to change its shape or quality) over the opening, leaving only a narrow, horizontal opening for light to escape.

The added length of the snoot shapes the light into a narrower, more even and defined line than the shorter barn door snoot, as the cookie is further away from the flash. The closer the barn doors, cookie, or light modifier is to the flash, the softer the edges of the light output will be.

Finally, you can even get a great effect by placing the barn doors on your flash, while it’s on your camera’s hot shoe. The horizontal banding creates a cool, dramatic effect.

If you enjoyed this post, check out Studio Anywhere 2, a new book that guides photographers in the art of shaping light using minimal gear.

About the author: Nick Fancher is a Columbus, Ohio-based portrait and commerce photographer. You can connect with him on Facebook here. You can also find more of his work and writing on his website and Instagram.