Taking Pictures on an Offshore Oil Rig Is Serious Business

![]()

Taking pictures on an offshore oil rig is serious business. For starters, due to the risk of flammable gas coming up the oil well, normal electronics are banned outside the living quarters. Smartphones are strictly forbidden and regular cameras require “hot work permits” be opened prior to use.

So to avoid that hassle, we use explosion-proof cameras. It sounds cooler than it is.

The first time I ever heard the term “explosion-proof,” it was at a job interview for an environmental toxicity testing facility. We were doing a tour and I saw the words “EXPLOSION-PROOF” in big red lettering on the side of a refrigerator! My mind immediately went to putting bombs inside it for safety, but all it really meant was that the fridge would not act as an ignition source if flammable materials (solvents, etc) were placed inside. Kind of disappointing.

Flash forward about six years, and working with explosion-proof equipment is now a part of my job responsibilities. We use airtight seals, gas purges, current-limiting devices, and all sorts of other methods to ensure nothing ever starts a fire if there is a gas release. This is a highly regulated area of engineering with very strict design requirements. Level sensors inside gasoline tanks, blower fans for grain silos, and coal mine excavators all must be designed according to tight standards such as ATEX.

These standards are intended for heavy industrial equipment, and can result in some absurd designs when applied to consumer electronics like cameras. Here’s a picture of our $5,000 explosion-proof camera:

![]()

Big, right? For $5,000 and the size of a brick, you would expect a high quality camera, but no. My flip phone in 2002 took better pictures. You have to hold it rock-steady for 5 seconds to get a decent picture, and the auto-exposure adjustment gives you all-white or all-black pictures about 10% of the time.

The rechargeable battery (that metal thing bolted to the front) dies in about 30 minutes. Zoom lens? Hah! Macro shots? Hah! It’s a terrible, god-awful camera — and it’s one of the best available. As a result of using this beast, I have gigs worth of blurry, grainy pictures from the rig. They’re good enough to put in a daily work report, but mostly not fit for publication on the Internet.

As a consequence of the mediocre options for getting good pictures outside, we resort to several workarounds. One is bringing whatever we need to photograph into the living quarters, where we can just use an iPhone. That’s how I got the picture of the red brick above. It’s easy and painless, as long as what you’re photographing isn’t greasy. Or big. Unfortunately, most oilfield equipment is greasy and big. Indoor shots are often not feasible.

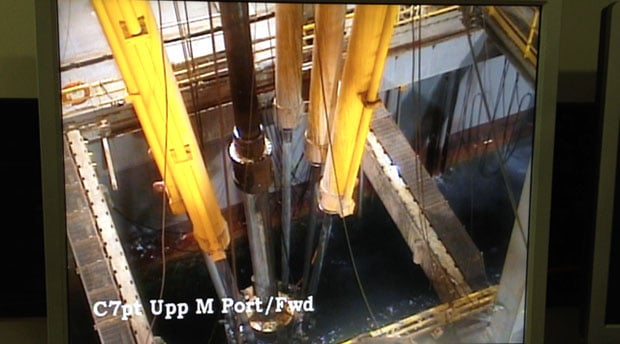

Another solution is aiming one of the rig’s CCTV cameras at whatever you’re interested in, and then taking a picture of the TV screen. This is probably the most ridiculous, round-about way to photograph something I can imagine, but getting screengrabs directly off the CCTV system requires bribing an IT guy to give a crap, which is usually impossible. So I just point my phone at the TV. Works well enough.

So those are the ways I usually take pictures. Sometimes, I stand on the smoke deck in the living quarters and just take iPhone pictures from there, like the shot that opened this article.

When it’s important, I go ahead and get the hot work permit and use a real camera. But as a general rule, if it’s important enough to need quality pictures, it’s sensitive enough that I shouldn’t post it on the Internet. Stuff like broken equipment, accident investigations, proprietary well construction processes, and so forth need to be cleared through the legal team prior to release.

I like my job and I dislike lawyers, so that means my best shots are never seen outside my company. It’s kind of unfortunate, because we have really freakin’ cool stuff out here, and the public almost never gets to see it. Here are a few pictures that I took on land, of some of the equipment I installed on a rig last year:

Occasionally, there will be an actual business reason to bring a professional photographer to the rig. This is a challenge for everyone involved.

- First off, you need water survival and helicopter crash training before you’re allowed to go offshore. Getting forcefully dunked upside-down into a swimming pool while buckled inside a helicopter simulator is a fairly steep barrier to entry for your average marketing photographer.

- Oil rigs are large, complex industrial installations with many hazards to inexperienced personnel. Getting into the middle of ongoing operations can be extremely hazardous to your health — there is moving equipment that can easily crush people to death, potential chemical exposure, extremely high pressure, swinging crane loads, and so forth. Something like 75% of all injuries offshore happen to people in their first 6 months of service. This means photographers on a 3-day visit are quite realistically in danger of serious injury if they’re not guarded by a dedicated keeper. I have been the keeper before… I once had to pull a guy out of the way of a moving pipe racker, because he was too busy looking through the camera lens to identify the 25 ton robot trundling towards him.

- People who are covered in sweat and grease, wearing dumpy flame-retardant coveralls, and under a lot of pressure to finish a job are usually not in the mood to play photo-shoot.

Then there are the lawyers. A few years ago, I was part of a marketing photo-shoot because I was one of the field engineers for a new, high-profile set of deepwater hydraulic equipment. A VP of Marketing came out to the rig with a photographer, and they spent a couple days staging scenes and sneaking candid shots. I was in several of the pictures, usually pretending to work on something complicated-looking, or interacting with a woman/minority for diversity purposes. When they finished, they told us it would be a while before we could see any of the pictures, because the legal departments of three different companies had to review and reject/approve every shot.

Very few candid pictures ever make the cut. Either a guy has his hand on something he’s not supposed to, or a proprietary process is being used, or a pair of safety glasses is momentarily removed. Sometimes, the picture happens to be four white guys watching a black guy work. Sometimes, there’s a person slacking off in the background. Sometimes, the rig floor just looks too dirty from that angle.

Once anything even remotely controversial has been weeded out, you’re mostly left with a lot of fluff and diversity-in-action shots. Here’s a “staring thoughtfully into space” shot of me on the Discoverer Spirit in 2009:

Sorry for the low res, I had to screengrab it when Schlumberger briefly used it as a splash page on their website last year. This picture took over a year to clear legal review by the Schlumberger, Transocean, and Anadarko legal teams. There is absolutely nothing interesting or controversial about it.

Note proper use of safety glasses, gloves, ear protection, hard hats, and hard hat secondary-retention straps. Note lack of visible grease or dirt. Note ethnic and gender diversity. Note my name being Photoshopped off my coveralls. Note my coworker pretending to studiously take notes.

With all the permits, rules, and legal considerations, it’s difficult to get decent pictures from my job that I can include in this article. Most of what I share and write about on the Internet use pictures I found on Google Image Search. That’s because I’m trying to walk a line to show the public some of what we do, without taking on the professional risk of releasing my own photos without explicit authorization.

How to take pictures is just one of the many safety and legal considerations that control everything we do in the oil industry.

About the author: Ryan Carlyle is a subsea well intervention engineer based in Houston, Texas. You can find him on Quora. This article originally appeared here.